How Toronto Non-Profit Honey Jam Is Helping Women Navigate the Music Industry

The stage where Nelly Furtado was discovered turns 25.

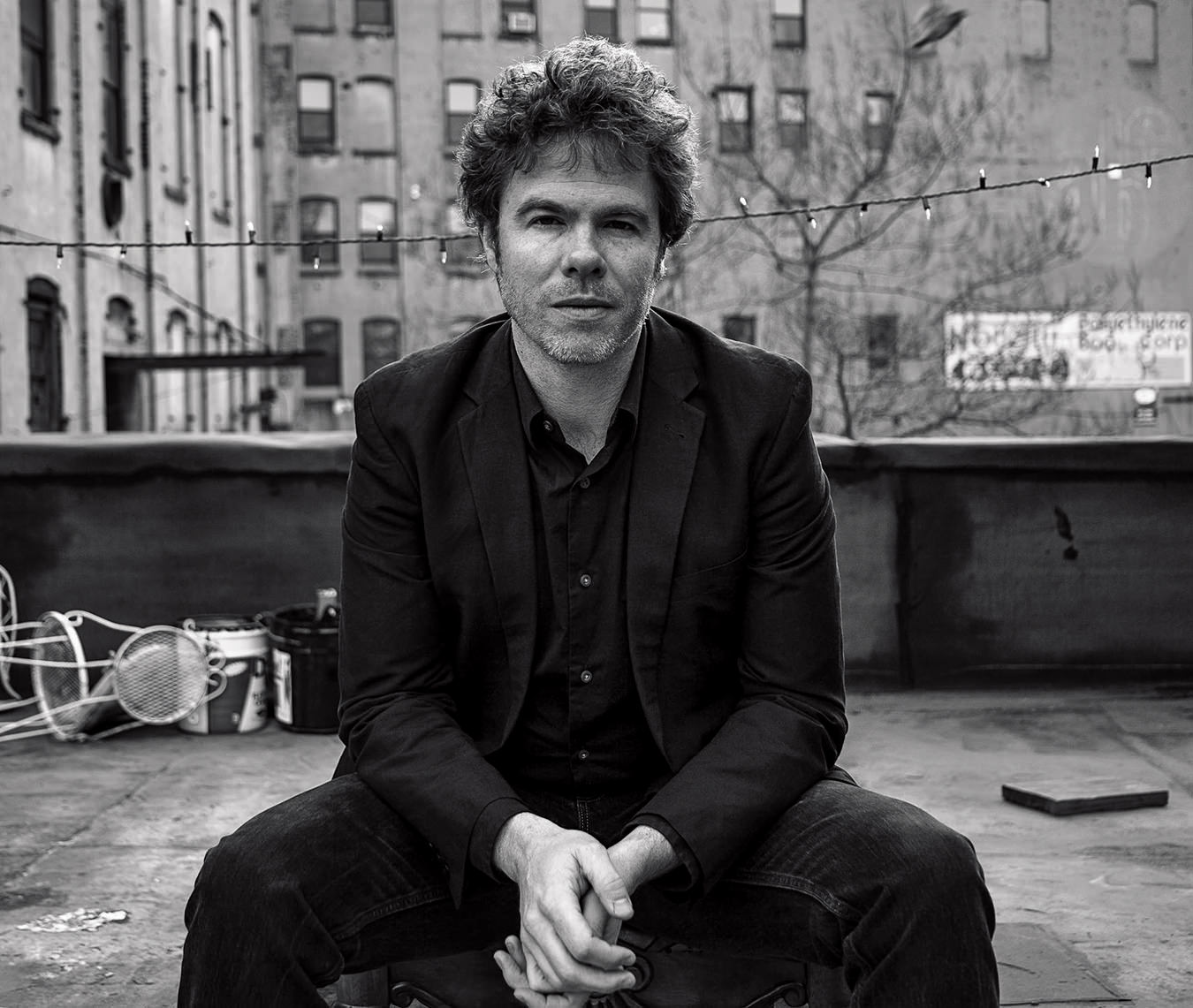

Ebonnie Rowe, founder of Honey Jam. Photo by @studiostudio246.

It’s been 26 years since Ebonnie Rowe approached DJX, the host of Toronto’s largest hip-hop radio station in the ‘90s—The Power Move Show—to speak out about the influence of misogynistic lyrics in rap music. It was a decision she came to while speaking to teenagers in her mentoring program, Each One Teach One, where young boys were using the same profanity they heard on the radio toward the girls in their life. “You didn’t have to have clean versions [of rap songs] at that time, and it was played in the middle of the day,” explains Rowe. In response, DJX gave Rowe three hours of airtime to talk about the issue on his show.

“There were a couple rappers outside waiting for me to beat me up,” Rowe tells me of the aftermath of her radio talk, which also touched on the problematic treatment of female rappers in the hip-hop industry. “Because how dare I say something about this treasured boys club genre. I didn’t know my place and they were pissed off.” (They never did beat her up, thanks to the intervention of someone at the station.)

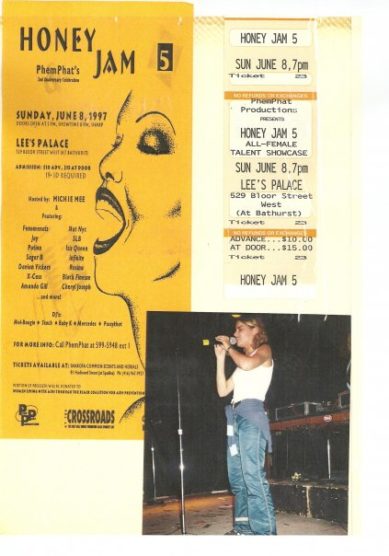

But since then, Rowe—a 2005 recipient of the YWCA Women Of Distinction Award—has been spearheading mentorship, education, and networking programs for female performers at her non-profit called Honey Jam in Toronto. Each year, a group of female-identifying musicians and performers audition to take part in Honey Jam’s programming, culminating in an annual concert where Nelly Furtado was discovered in 1997 and other stars like Jully Black and Melanie Fiona also graced the stage. A more recent alum is Polaris Prize winner Haviah Mighty, the first black woman and hip-hop artist to win the prize.

Memorabilia from Nelly Furtado’s career-changing performance for Honey Jam in 1997.

Beyond giving female artists the chance to be mentored and coached by established musicians and previous alumni, perform on stage, and network at high-level music industry events, Honey Jam also offers workshops on the business of the music industry—a business still predominantly ruled by men. “In 1996, we started doing workshops because girls would get preyed upon and they didn’t know who was legit and who wasn’t. They didn’t know what [contracts] they were signing. They didn’t know anything about the industry,” says Rowe. “All the producers were men, and they would approach the girls with the whole ‘Oh baby, I could make you a star.’ And I wanted [the women] to be educated.”

This year, which marks the 25th anniversary for Honey Jam, will see a host of special programming in celebration of a quarter century’s worth of slow-but-steady progress, including workshops on the technical side of music-making. “We definitely need more female producers,” says Rowe, explaining the prevalence of harassment facing women in traditionally masculine music-related jobs. “The [people] who own the clubs, run soundchecks, run the tours, [and] all the stage management are still overwhelmingly men.”

Rowe cites Toronto artist Jessie Reyez’s music video for the song “Gatekeeper” as a representation of the music industry’s dark underbelly. The video exposes the sort of “casting couch” behaviour that has, until recently, been an unspoken norm for many female artists trying to make it in the industry. “It really broke my heart,” says Rowe of the music video.

“The #MeToo era is exposing all of these things, [and it] makes you know why programs [like Honey Jam] need to exist,” says Rowe. “Having a safe, protected, and supportive space from people who just want [artists] to succeed.”

It seems fitting that the day I interviewed Rowe, Harvey Weinstein was charged with two counts of rape and sexual assault. The entire discourse of the #MeToo movement has been interwoven with his case and though Weinstein was accused by over 100 women, only two cases saw him charged in a trial. But there is something to be said about Weinstein being charged at all. It’s a menial yet undeniable move towards something resembling progress.

Rowe understands the fragility of this progress; while the last decade has seen much more representation of women in the industry, the upper echelon are still men. “When I first started [Honey Jam], I said my biggest goal was for it not to have to exist because we would be on this level playing field,” says Rowe. “And I do think we have made a lot of strides, but nowhere near where we should be.”

While the ultimate goal of Honey Jam is to be unnecessary, as long as the need exists, Rowe plans to continue providing support for both newcomers to the music industry and past alumni. “It’s a sisterhood that’s a lifetime thing,” she says. “Once you’ve done it, you’re always in it.”

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.