Cape Breton’s Beolach Is Keeping Celtic Folk Music Alive

Meet the Nova Scotia band carrying the torch.

On Cape Breton, on the easternmost tip of Nova Scotia’s Atlantic shores, folk music serves as a way to connect islanders with their Scottish roots and for Cape Breton’s musicians to connect with an ever-changing Scotland.

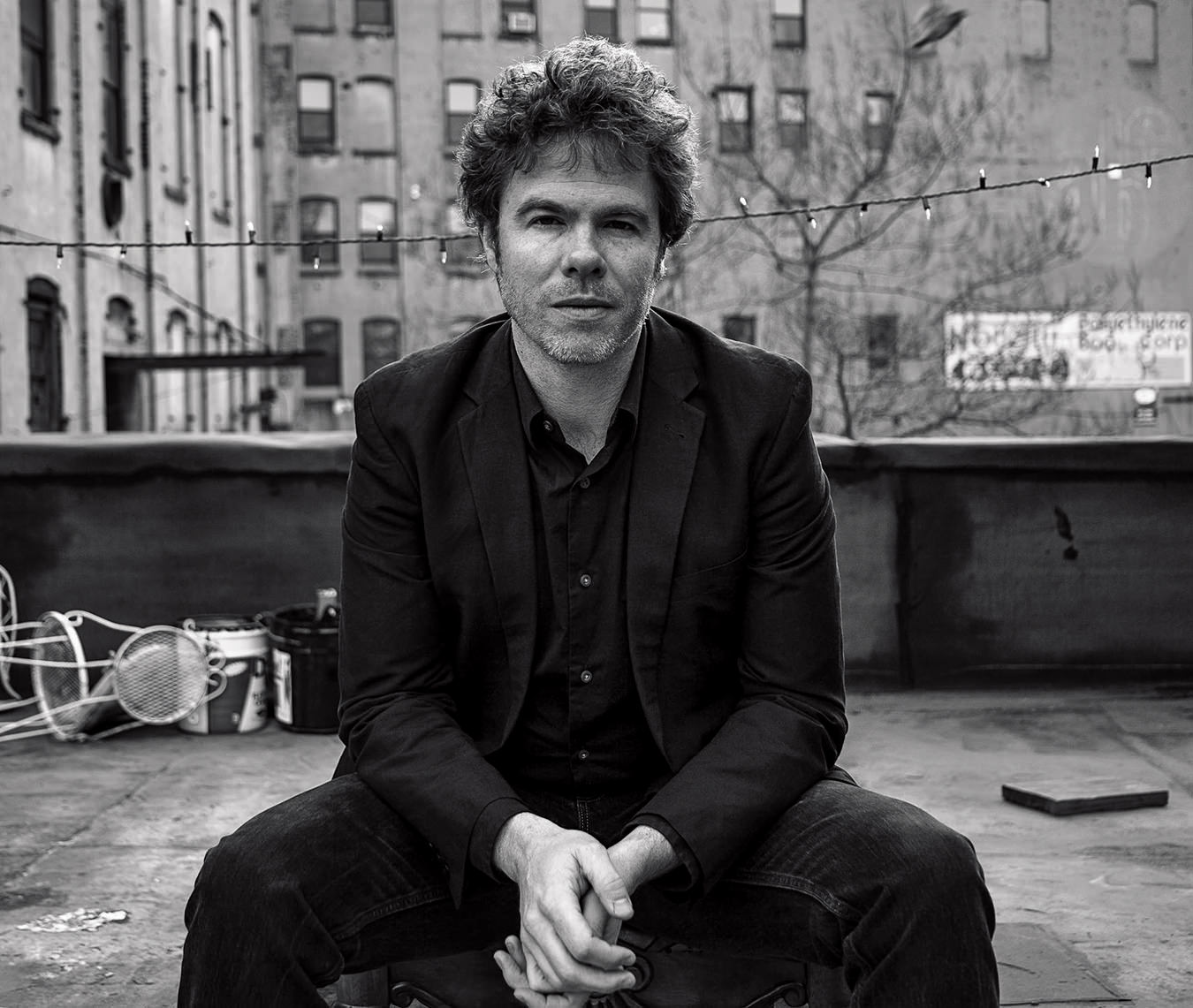

“As Cape Bretoners, the shared history we have with Scotland is something we think about on a daily basis,” says Mac Morin, piano player with Cape Breton Celtic folk stalwarts Beolach. “I mean, some of the place names here are the same as they are in Scotland. It’s really hard to escape it when you’re getting slapped in the head with it every time you drive down the road.”

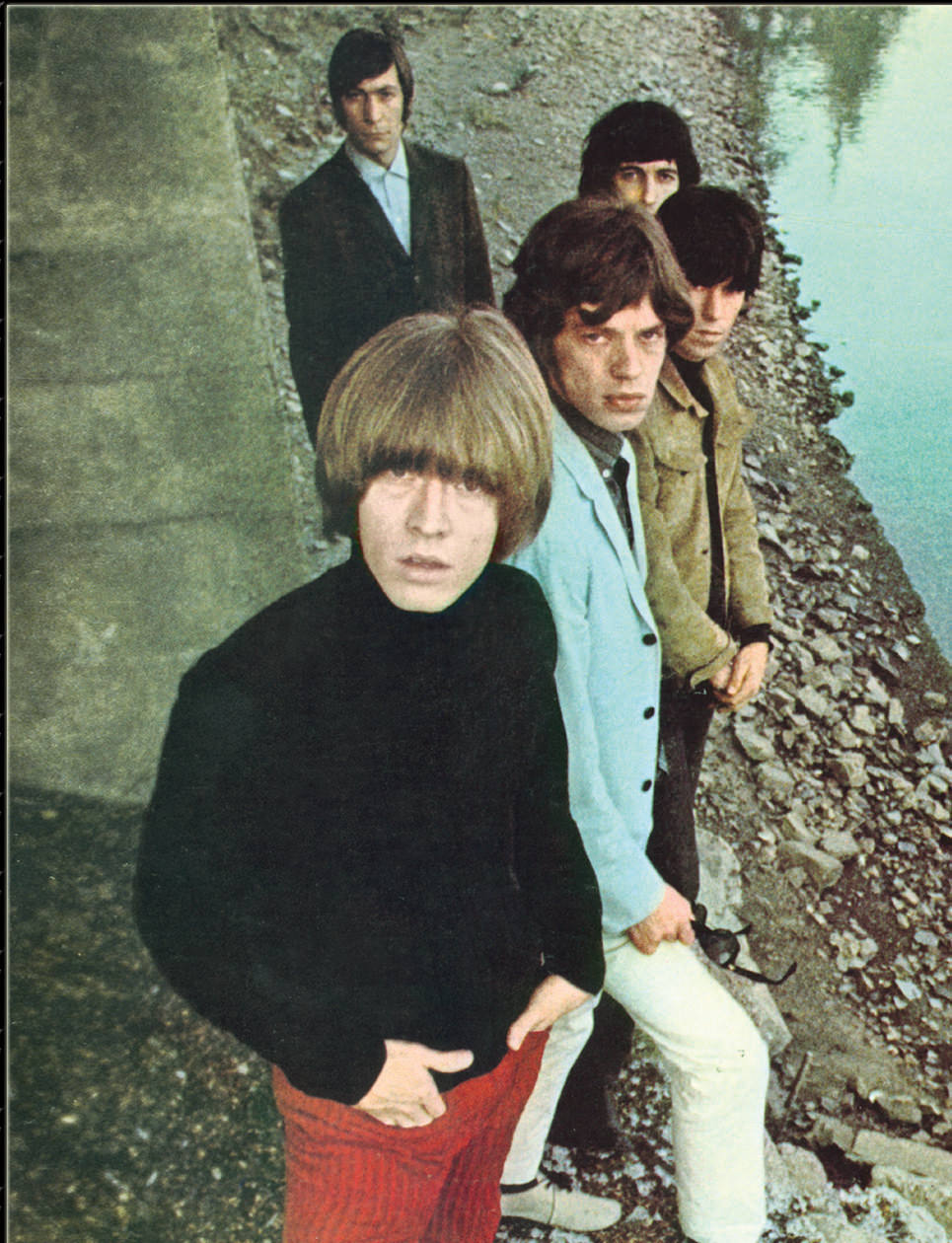

Cape Breton has been steeped in traditional Celtic folk music, imported directly from the highlands and islands of Scotland, ever since the first waves of Scots fleeing the Highland Clearances and seeking a new life in the Americas lapped up on its shores in the late 18th century.

“We know our culture came over with those first peoples,” Morin says. You can’t put much on a boat for the journey—but they did have their culture, and it was a living culture. The language, and the dancing, and the playing—that was part of their life. That’s what helped them get through being in a new place.”

“The smaller the place you’re from, the more you’re going to put into keeping something alive,” says Mairi Rankin, one of Beolach’s fiddle players and native of Mabou whose mother came to Cape Breton from North Uist in Scotland’s Outer Hebrides. “The island was an island until 1955 when the causeway was built. Nothing changed, you know. That culture and language was kept as true to form as possible.”

In that spirit of preserving the culture down through the generations in its purest form without dilution or variation, folk music on Cape Breton can sometimes tend toward the dogmatic, with audiences appreciating that rules are rules for a reason.

“Those concerts in Mabou were the hardest things in the world to play at because you had the fussiest audience,” Morin says. “They all knew what the tune was supposed to sound like, and they didn’t want you stepping outside that line, and then they’d tell you if you’re going too fast. Those were the things that helped you stay within the white lines of the road.”

“There are these kind of unspoken ‘guidelines’ that you don’t move too much,” Rankin explains. “There’s an allowance for this and that, but for that Cape Breton sound and style, there’s check marks that you have to keep within. It’s funny, sometimes people from home can be your biggest fans, and that does keep us in line. You can try something new, and they’ll be like ‘mmhmm,’ so you just go back to the old King George sets, and they’ll love that as much.”

Wendy MacIsaac, the other half of Beolach’s fiddle duo, says, tentatively, “People outside of Cape Breton definitely have more… enthusiasm. People don’t clap along to the music ever. They tap their foot quietly along as you go from one tune to the next. You might hear a little ‘yeo!’ coming from the back of the hall—that’s your pat on the back.

Folk music travels have often taken Beolach back to their ancestral homeland, where they have sometimes found the changing face of Scottish folk music to be at odds with the folk scene back home.

“A lot of the young Scottish bands are bringing lighting rigs on the road now. All of that is propelling them into a whole different league of playing, and festivals, and whatnot. Playing at Ceòlas in South Uist though, that felt pretty close to home with that kind of close-knit community. You could just pick up all those people and drop them on Cape Breton,” Rankin says. “It’s crazy, but it all comes down to learning tunes at the end of the day.”

As Scotland’s contemporary traditional music scene spins off on its own journey, Beolach and the musicians of Cape Breton are keeping the tradition alive in its purest form—the way generations of Cape Bretoners have done for centuries.