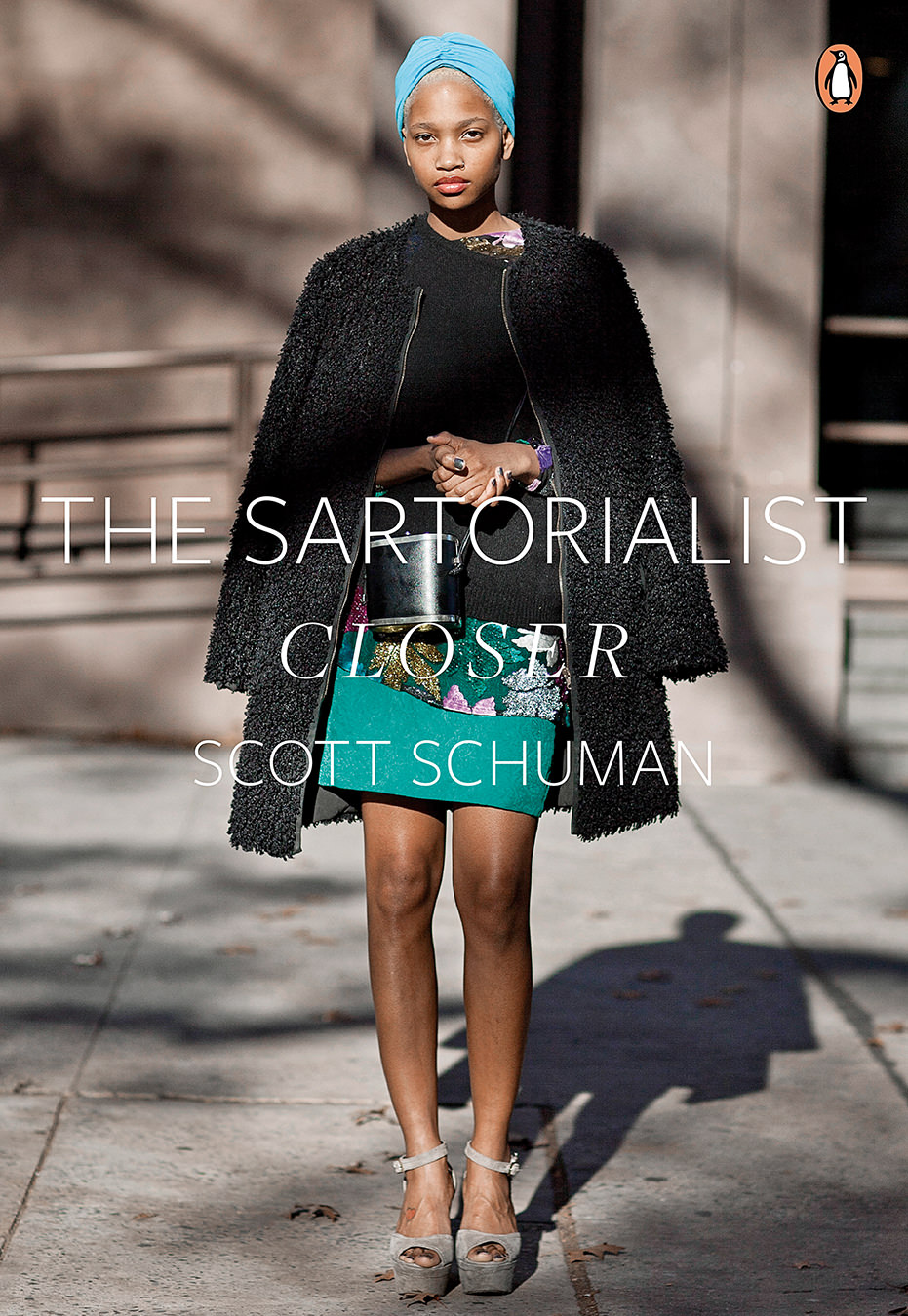

Textiles and Tradition: a Conversation on Appropriation With Indigenous Artist Jaad Kuujus

How brands and consumers can collaborate to foster, not appropriate, culture.

“I love being well dressed when going into nature, thinking that nature can see me.” <i>Image courtesy of Douglas Reynolds Gallery.</i>

Meghann O’Brien (who works under the artist name Jaad Kuujus) creates works that embody a balance between her cultural heritage and her passion for creating functional designs. The Vancouver-based artist says that “when it comes to clothing, I tend to be drawn to things that are beautiful, simple, but also functional.”

Of Haida, Kwakwaka’wakw, and Irish descent, O’Brien is inspired by both her rich cultural heritage and her former life as a pro snowboarder when designing. “Lately, I’ve been drawn to wearing clothing that is very loose, a kind of floating cocoon. My aesthetic tends to be grand and layered, billowy dresses or pants under dresses. There’s a tendency to categorize our wardrobe for life events—fancy items and regular day-to-day pieces—but I tend to wear what I love to wear.”

Meghann O’Brien works under the artist name Jaad Kuujus. Here she poses with an original piece of adornment. Photo by Stasia Garraway.

This sometimes makes her seem overdressed, but O’Brien thinks nothing of wearing one of her favourite dresses on a hike through the rain forest. “I love being well dressed when going into nature, thinking that nature can see me.” Her desire to wear seemingly “fancy” fashions is a way to incorporate the sacred, the special, into her daily life. “More quality items do not need to be tucked away for only special events,” she feels.

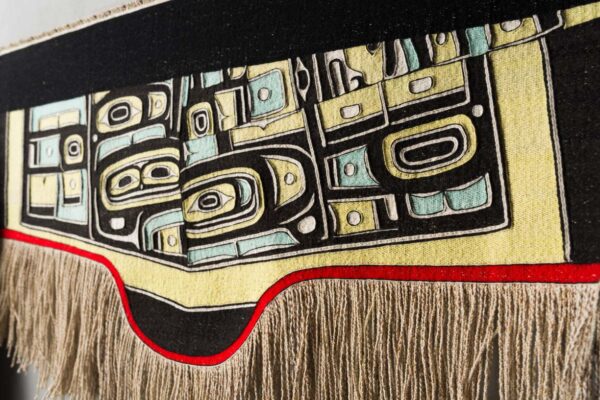

O’Brien is sought after for her intricate ceremonial regalia. These pieces, she explains, have a specific function in Northwest Coast society. Though the ceremonial aspects of Indigenous communities have been interrupted and are constantly changing, she references a cultural tradition to dress Indigenous leaders in a way that recognizes her ancestors. “Today this regalia is mostly made as art pieces on commission for private collectors or institutions,” O’Brien explains. She would like to see the work transform in a way that honours how it’s meant to be worn. As a global society, we need to be mindful of how we incorporate these traditional and richly significant cultural fashions. “It’s not appropriate for someone outside the culture, who isn’t a chief or matriarch or dancing on behalf of one, to wear a Chilkat or Naaxiin ceremonial robe, because the pieces are for a specific use and there’s something sacred about them,” O’Brien says.

“I am passionate about quality and how it can redefine our concept of luxury. I think reframing that concept as consumers is key.”

“There’s a strong tie between rights and responsibility, and how we care for knowledge, and how not all things are meant for all people, how even in our own families not all songs/dances are enacted by anyone and everyone, and those rights to perform them can always be taken back if one isn’t upholding the responsibility that goes with them,” O’Brien notes.

Leg wear by Jaad Kuujus. Photo by Stasia Garraway.

Bigger brands tend to appropriate the superficial aspects of a culture. O’Brien, like many Indigenous creatives, is concerned that if there’s no long-term engagement with the creators of the artwork, we risk seeing these designs brought into a fashion house and used incorrectly. She feels the way they are being absorbed into mainstream fashion and turned into a trend is completely opposed to what the original designs represent for Indigenous people. Appropriation, O’Brien says, “feels like the life is being sucked out of our people, our way of thinking is being transformed, and the foundations are weakened.”

In the last few years, there’s been a growing awareness around cultural appropriation of Indigenous (and other) heritages and style. But how do we shift toward a more mindful, respectful awareness when incorporating inspiration from Indigenous culture?

O’Brien points to the Italian brand Daniela Gregis. “I have a lot of respect for Daniela Gregis, the brand is the epitome of Indigenous ethics even though they’re not native,” she says, noting that fabrics are hand-loomed or hand-painted, almost everything is made in Italy, which the company is proud of, and virtually nothing is thrown away. “It’s beautiful and made with integrity, with respect for tradition and the handmade,” she says. “To me, this brand is one of the biggest hopes for humankind and the future of fashion.”

Image courtesy of Douglas Reynolds Gallery.

O’Brien is pleased that more brands are keen to partner with Indigenous artists and designers and to pay for use of their designs. She applauds Valentino, who created a dress with the permission of Métis visual artist Christi Belcourt. It’s equally important to highlight and support Indigenous people who are creating their own brands and platforms. This includes Jamie Okuma, Bethany Yellowtail and her B. Yellowtail Collective, Sho Sho Esquiro, Yolonda Skelton, and Warren Steven Scott, who is exploding on the fashion scene with his stunning contemporary designs. “There is so much to celebrate,” O’Brien says.

“Appropriation is especially problematic when done by a culture that doesn’t place as much emphasis on North American Indigenous history,” O’Brien observes. There remains a lack of care or respect, which is inevitably destructive and upsetting for many Indigenous people, she says.

So where does the responsibility fall? Consumers need to be both interested and informed. O’Brien points to brands like Totem Design House with Andy Everson and Erin Brillon as “a great example of how both the traditional values of our people and western capitalism can be in service to both our people and greater society, connecting them to our culture and fostering a deeper understanding. It puts the purchase of commercial goods at the service of the continuation of culture.”

“Lately, I’ve been drawn to wearing clothing that is very loose, a kind of floating cocoon. My aesthetic tends to be grand and layered, billowy dresses or pants under dresses. There’s a tendency to categorize our wardrobe for life events—fancy items and regular day-to-day pieces—but I tend to wear what I love to wear.” Image courtesy of Douglas Reynolds Gallery.

Image courtesy of Douglas Reynolds Gallery.

Because brands are feeling the pressure and responding in a more positive way, there’s hope. The equity or legal-parity aspect of appropriation is being addressed, but how do we ask consumers and fashion producers to collaborate in a way that doesn’t disregard tradition? O’Brien looks to fostering more Indigenous-led or -run companies. “I want to project the possible impacts of a certain direction of choices made today and what that will mean for generations down the road,” she says. What she doesn’t want to see is “companies simply hiring our people to take on roles, without the institutions actually changing. Our people and non-Indigenous allies are banging at the doors of institutions and companies for fair representation and inclusion across the board.” She firmly believes that having Indigenous representatives included in the discussions changes the conversation.

At the same time, O’Brien acknowledges that we can’t all be anthropologists. “Ideally, we build more connections,” she says. “The more we can sustain and support the production of handmade goods or commercial goods produced with a bigger framework than just profit in the end, the better.” Quality over quantity is a good place to start, she notes. “Expensive items have a reason for being so expensive: either people being paid properly or caring for the land, et cetera. Maybe questioning why something costs so little could be the counter to that as consumers.”

Photo by Stasia Garraway.

How does she envision the future of Indigenous fashion? “My hope is that someone will see the hole in the world of textile production and pick up some of the fibres that are used on the coast and have huge potential as a commercially produced fibre, like stinging nettle. We have a lot of catching up to do with not only regaining our traditions and skills but with incorporating them into a globalized world.”