How a BC Indigenous Community Is Creating a Micro-economy Through Wellness

It all starts with the land.

Hada (Bond Sound) where Nawalakw is currently under development.

In 2005 Sherry Moon blockaded a road with her brothers, great aunt, and one of their chiefs to prevent a logging company from deforesting sacred area in Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw territory. They had found out this logging was taking place by coincidence—her uncle happened to be flying over on his way back from a meeting and spotted the operation.

When he landed, he gathered his family and explained to Moon their responsibility to the land. Before she left, Moon recalls how her grandfather told her, “we can bitch and complain about our territory and what the non-natives are doing out there, but if we’re not going to use it, what’s the point of fighting for it?” She says, “that stuck in my mind since then, and that’s kind of my drive.” That first deployment, which lasted a month, was the beginning of a journey of stewardship for Moon that has culminated in her involvement with a progressive revitalization model in the Great Bear Rainforest of British Columbia.

After several years as a guide for the Indigenous-run tourism company Sea Wolf Adventures, she is now the training and employment manager for Nawalakw, a language revitalization and healing centre in Hada (Bond Sound) that will support and employ the Indigenous community of Kwakwa̱ka̱’wakw and be funded by an adjoining wellness eco-tourism lodge that operates in the summer months.

Moon was brought on to the project by executive director and hereditary chief K’odi Nelson, who first envisioned a camp in Hada four years ago. Similar to Moon’s story, Nelson also realized the need to establish a physical presence in the territories affected by heli-logging. He knew he needed to build something, so he began to collect roof tresses and scraps from local carpenters with a plan to erect a shack on the beach.

As a culture and language teacher, Nelson often took local band children from Port Hardy out onto their traditional territories, and he witnessed first-hand how they flourished and retained the language there in a way that was more natural than in a classroom. Nelson explained to the children, just as Moon’s uncle had explained to her, that when we become disconnected from the land, it is easier not to care about it. He says, “our people need this land and the land needs us.”

The idea of a culture camp was born out of these experiences and a desire to protect the area for future generations and teach the current ones “to be proud of who they are and where they come from,” he explains. The shack became a fleeting idea as Nelson started dreaming of a more permanent site dedicated to Indigenous well-being. The new plan would mean a lasting and empowering presence on the land—one that could not be disrupted.

The Phase 1 construction site from above.

To make this dream a reality, Nelson sought the advice of people who he has dubbed his “Jedi council.” He asked tree planters in the area about living in the wilderness and spoke to Becky and Fraser Murray who run the successful Nimmo Bay Lodge in the traditional territory about its operations, but it was the Fogo Island model that really helped Nelson’s vision click into place.

When the fishing industry died out on Fogo Island, it had a significant effect on the 400 years of culture that had existed up until that point. The inn, which is now a world-class success story, is based on the cultural knowledge that would have otherwise been lost if not for hotelier Zita Cobb. The inn redirected the knowledge of local craftsman from building fishing boats and sewing clothes to making all of the furniture and quilts for the hotel.

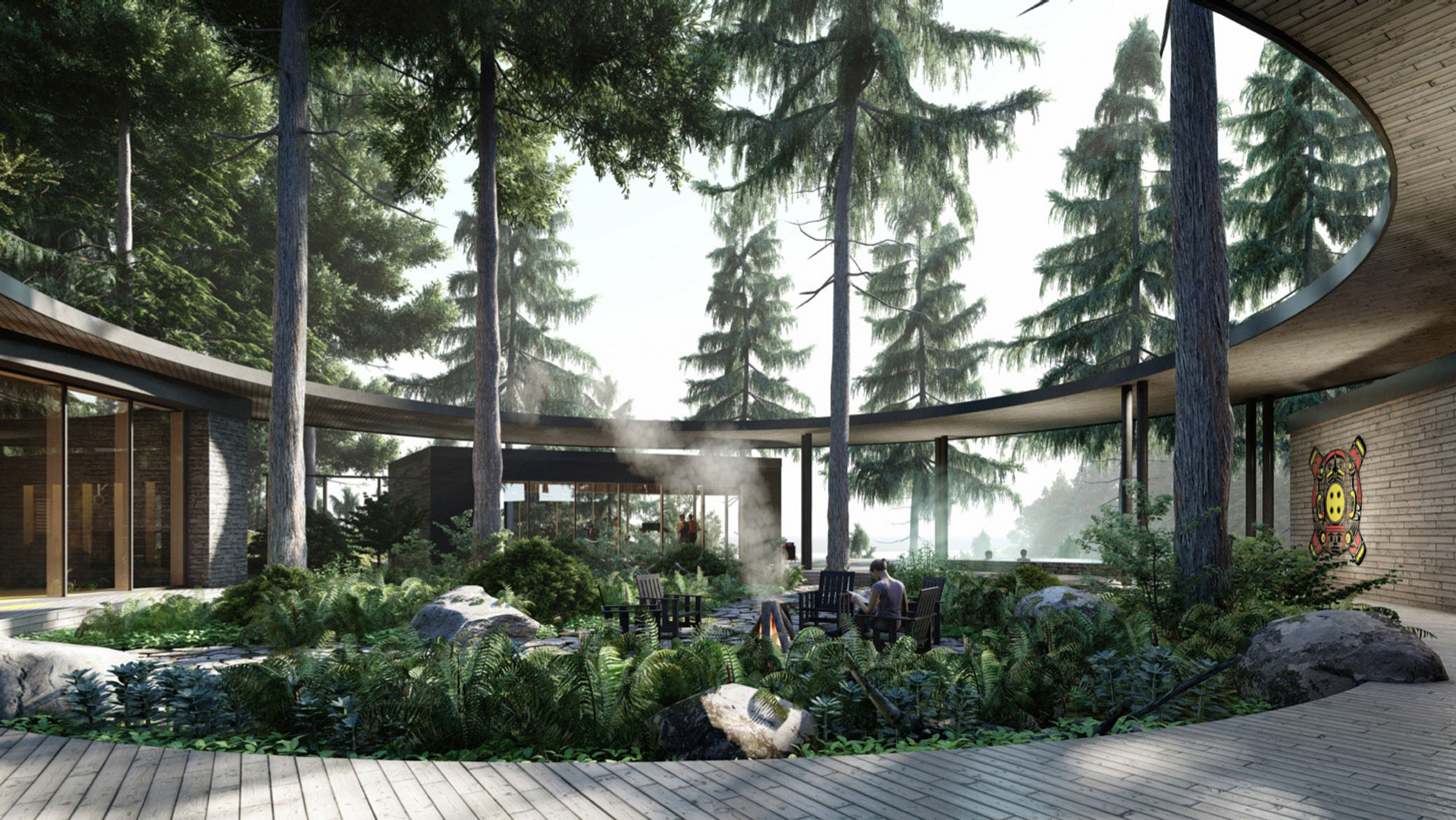

Nelson examined these methods and took it one step further by combining tourism with Indigenous enterprise and cultural healing. “People can make a living from being who they are,” he says. The culture camp, which is already under construction, will sit across the river from the healing village (Phase 2) and offer language and culture revitalization and mental wellness programming. For its part, the eco-lodge—whose early renderings were designed by Seattle-based architect and creator of the living building challenge Jason McLennan—strives to be the first lodge in the world that is 100 per cent self-sustaining. It will also generate employment for the community and ensure that people don’t have to relocate to find work, as they do currently.

Jason McLennan rendering of what Phase 2 may look like.

Nelson says that the circular micro-economy this project will generate is meant to instill pride in their people’s children as they look across the river and hope to one day work in the healing village. At the same time, guests of the eco-lodge will look back and want to learn more about Indigenous culture and get involved in the issues of Indigenous land sovereignty.

Phase 1 is expected to be completed by April 2021, and the first cohort from local schools will arrive for the inaugural language program by May or June. Shortly after, they hope to begin work on the eco-lodge and Phase 2, which is currently being fundraised.

For now, Moon arranges for the young people interested in working at the lodge to train at similar eco-lodges around Vancouver Island like Nimmo Bay and the Wickaninnish Inn, learning the ins and outs of tourism.

“In three short years, we went from a crazy dream to laying the floor down on Phase 1,” Nelson says, smiling.

Phase 2 which is in the planning stages, will be a healing village and eco-lodge open for tourism in the summer months. Rendering by Jason McLennan.

Moon echoes the sentiment, saying: “When I finally got to the site, I was in tears. It’s a dream come true—a huge dream of ours. It’s very heartwarming, and the energy that I feel when I’m there—it’s breathtaking. I don’t know how else to put it; it’s just absolutely incredible to be able to to witness history in the making. It’s a huge, huge step for our people.”

Moon and the team are also working to rebuild an old trail that connects the mouth of Kingcome inlet to Bond Sound, the birth place of the Ḵwikwa̱sut’inux (Gilford Island People) and the site of Nawalak. The trail will allow people from Kingcome Inlet and Gilford Island to commute back and forth and be employed by the lodge.

Nawalakw is being built using the traditional knowledge of the Musga’makw Dzawada̱’enux̱w (The Four Tribes of Kingcome Inlet) to create a place where their connection to the land will never be lost.