Canadian Author Naben Ruthnum Talks Technology and Diversity Politics

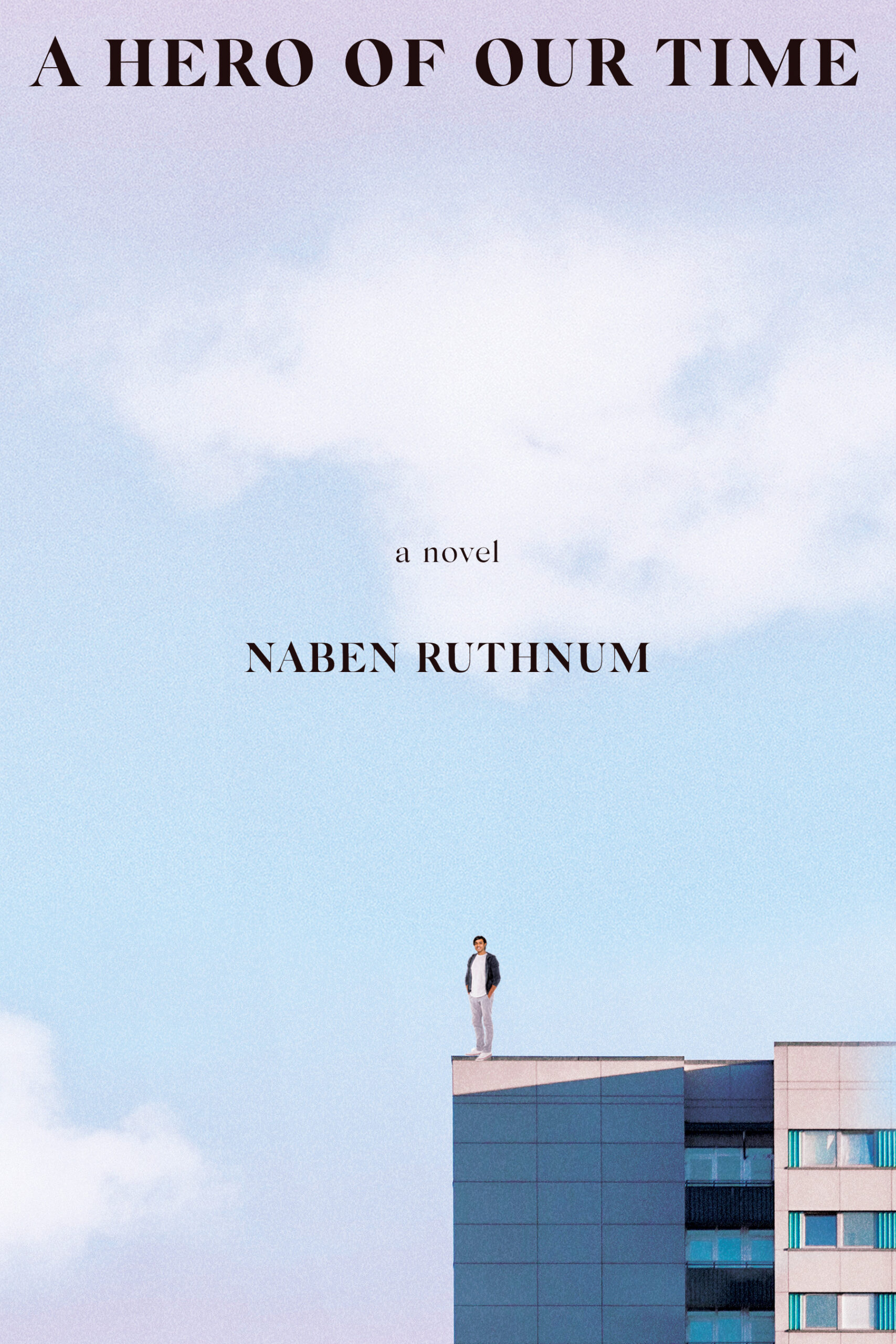

In his new book A Hero of Our Time, Ruthnum offers a fierce critique of the tech world and the profit-driven strivers who populate it.

Naben Ruthnum has had a presence in the Canadian arts scene for years, so it’s a bit of a surprise that we’re only now getting his first true literary novel. Readers will know him from his journalism, essays, and his celebrated book Curry: Eating, Reading, and Race—or maybe as Nathan Ripley, author of two smashing thrillers. But Ruthnum is a student of form as much as substance, and his latest novel was the only way to contain some of the sweeping ideas about technology, diversity politics, and the modern workplace that had been nagging at him for months. In A Hero of Our Time, Ruthnum offers a fierce critique of the tech world and the profit-driven strivers who populate it. We caught up with him at home in Toronto to talk about it.

Why were you compelled to write this book? Why now?

There were so many ideas in the ether, political ones and personal ones. It was all I talked about in my day-to-day life with my friends: diversity politics, ways of leveraging power in both the arts world and the business world, the erosion of the education sector by tech, and the solutions that are presented to universities by tech companies actually being tacit attacks on the education system and how people actually learn. All of which come down to my growing obsession with how power is shaped in the modern world. I realized I don’t know how to write about this in essays or online. But a novel makes a lot of sense. So it was a repository for my jokes and my obsessions and my torments.

What are some of those torments? Let’s get more specific.

Just seeing the personal will to power of so many different individuals wrapped up and packaged in popular left-leaning politics. (And of course this happens with centrist and right-leaning people all the time, but that tends to be talked about more.) The way that opinion columnists can manipulate their way into running magazines or attaining political power by disguising their self-interest as what ordinary people really want. And in my sectors where I work, I see diversity politics being packaged and used as stepping stones towards power. And not often from people from afflicted groups. My main villain, Olivia Robinson, is very brilliant at using the diversity of the employees around and eventually below her to elevate herself to the ultimate position.

I assume you read that Substack piece about the CBC the other week?

As soon as someone starts attacking “woke culture,” I stop taking them seriously immediately. There are so many things packaged in what you mean by woke. Somebody who uses that term really easily has such an enormous blanketing effect. That’s not somebody who thinks about individuals or power. There is tons to criticize the CBC about—there’s definitely tons of this diversity window-dressing stuff that I talk about. You can sometimes see on the CBC Books list, for example, the math that went into it, making sure there are just enough books by Group X here, not too many by Group Y there. But to cherry-pick things like that to say this isn’t why we’re not covering class struggle is absurd.

So how do some of these ideas play out in your world, the Canadian art world?

One great thing is we’re getting more books from people of colour than ever before. But if you actually look at who’s behind the editing desks—I encourage you to look into the demographics of it. The diversity movement in the upper levels of Canadian arts and publishing I think kind of stopped with gender-balance stuff. There are tons of women employed in these fields now, which is amazing. But in terms of actually correcting the diversity of people who can pick who gets published and where the money goes, not so much. So that was something I was interested in exploring in this sort of mirror world, in terms of diversity in tech.

But also, if you look at my own publishing career, I think still to this point my thriller novels did solidly, but in terms of what I’m known for (to the degree that I am known), it’s definitely for my culture politics and race writing. Even if I’m being critical of it, it remains a fact that it’s been a massive asset in my career that I’m a person of colour who writes, sometimes, about issues that are relevant to people of colour—and in a way that white liberals find interesting. Because ultimately so much of the book buying public are white left-leaning people. But some of my best friends are, too.

You write under two names: your own, and Nathan Ripley for your genre stuff. Why anglicize your thriller pen name?

When I was 14, I thought that I’d want to have two careers, one in pulp and one in literary fiction. That’s when I chose that pseudonym. It wasn’t specifically because it sounded like an anglicized version of my name. Ripley came from Alien. I hadn’t thought about the racial dimensions of it at that time. Certainly, by the time the first Nathan Ripley book was close to being published, I realized it sounded like I was making a white box for myself. I don’t think it benefited me at all, but as a writer it freed me of any expectation to write works of literature that sort of matched with my name. I’m sure there are some backroom whispers in genre-writing land about how I’m white-facing or something like that. I could give a fuck.

What about the distinctions between genre and literary fiction?

My thrillers are more reader-facing. When I wrote A Hero of Our Time, I was certainly thinking about the reader experience, but making it compelling and absorbing and hopefully page-turning wasn’t as plot- and movement-based as it was in a thriller. Really immersing yourself in the consciousness of my central character was the main appeal for me. Whereas when I’m working on a thriller, I’m always thinking story first. Shifting back into that mode is always a challenge. I’ve started and trashed three different ones before settling on one.

What was the main critique you wanted to make in the new novel about the tech world?

This is a big blanket statement, but there’s a real forward-looking, progress vision that has an extreme amount of disdain for the past. It involves thinking of the past as entirely retrograde, that there’s nothing we can bring forward usefully into the present. It’s also just so incredibly fixated on maximum profit. Even if the product isn’t profitable, maximum investment in this product that may someday be profitable. It’s both incredibly successful and also a massive con. There are so many nonexistent products that have billions of dollars flowing into them. And just the presence of all that money ends up generating more money. The book is certainly not an anticapitalist screed, but it’s definitely asking [the reader] to take a good strong look at what our actual benefits are from believing in tech as a solution. And let’s just laugh at how they pretend to care about diversity.

Is this a world you have any direct experience in?

I’ve worked a lot of tech-adjacent social media/advertising jobs before my other writing stuff picked up. I actually enjoyed those jobs. A lot of people in them were people from journalistic or creative writing backgrounds. It’s interesting to be around lots and lots of money. Flows of capital. You end up taking home decent paycheques, and then you compare those to the massive profits or the salaries of people you had staged interviews with earlier that day to turn into social media fodder. It was an intoxicating world. But you have to be a completely different person than I am to be a success.

Any idea how to fix any of these broken institutions?

Nothing worth talking about. Good literary novels don’t have a functional purpose. If there’s a goal with this book that is practical, somebody who does have a practical role in these worlds will reflect on them and make change. Thinking about where money goes is the only way these systems actually change. And questioning those who have it. And questioning those who want it and their motivations.

Don’t we all want it?

Of course we do! The hero of my book is a person of colour; he’s struggling against what he thinks is an unfair exertion of power by a white person. What could be more heroic in a 2022 book? Not this guy. He’s so incredibly self-absorbed that he can’t relate to other people or see how driven by power and revenge he is. I think questioning that impulse is what saves you.

Who are you reading right now?

Sadi Muktadir. He’s the most exciting up-and-coming writer that I’ve read in a long time. His first book is coming out soon, and it’s a book about four young Muslim men in Toronto just doing dirtbag stuff. It got my attention as being utterly atypical. I read so much old stuff that I sometimes find myself at a loss. I’ve also tried to get better at French lately, so I’m reading the latest Prix Goncourt winner. I find it’s too hard for me, but it’s also really exhilarating to focus so purely. And the (last) novel I’ve read that just blew my socks off was Thomas Bernhard’s Correction. And I’m really excited about Waubgeshig Rice’s next novel, and Andrew (F.) Sullivan’s. There’s some exciting stuff happening.