Indigenous Voices

We revisit stories of resilience, hope, and culture on the long road to truth and reconciliation.

Photo by Guillaume Simoneau

Art Imitates Life: Walter Scott and His Comic Book Doppelgänger

“I’m fascinated with people losing everything and crawling out of it,” Walter Scott says of The Wendy Award, the fourth and newest instalment of the Kahnawà:ke-born Mohawk artist’s cult-favourite comics. Over the past decade, readers have followed Wendy through Canada’s art world, from her roots as a Montreal punk to graduating with a master of fine arts at “University of Hell,” Ontario. —Rebecca Peng

___

Photo by Ted Belton

The Director’s Cut: Kaniehtiio Horn Uses Comedy to Combat the Trauma of Anti-Indigeneity

The profound racism and countless tragedies Indigenous people have experienced over hundreds of years are no laughing matter. Yet for actor, writer, producer, and director Kaniehtiio (GANYE-dee-yo) Horn, comedy is a force that can be used to better the lives of herself and others. “How would we get this far if we were just walking around angry?” she remarks from her home on the Kahnawà:ke Mohawk reserve south of Montreal. Comedy “is part of our survival. I’ve grown up hearing laughter in the craziest times.” —Bernadette Morra

___

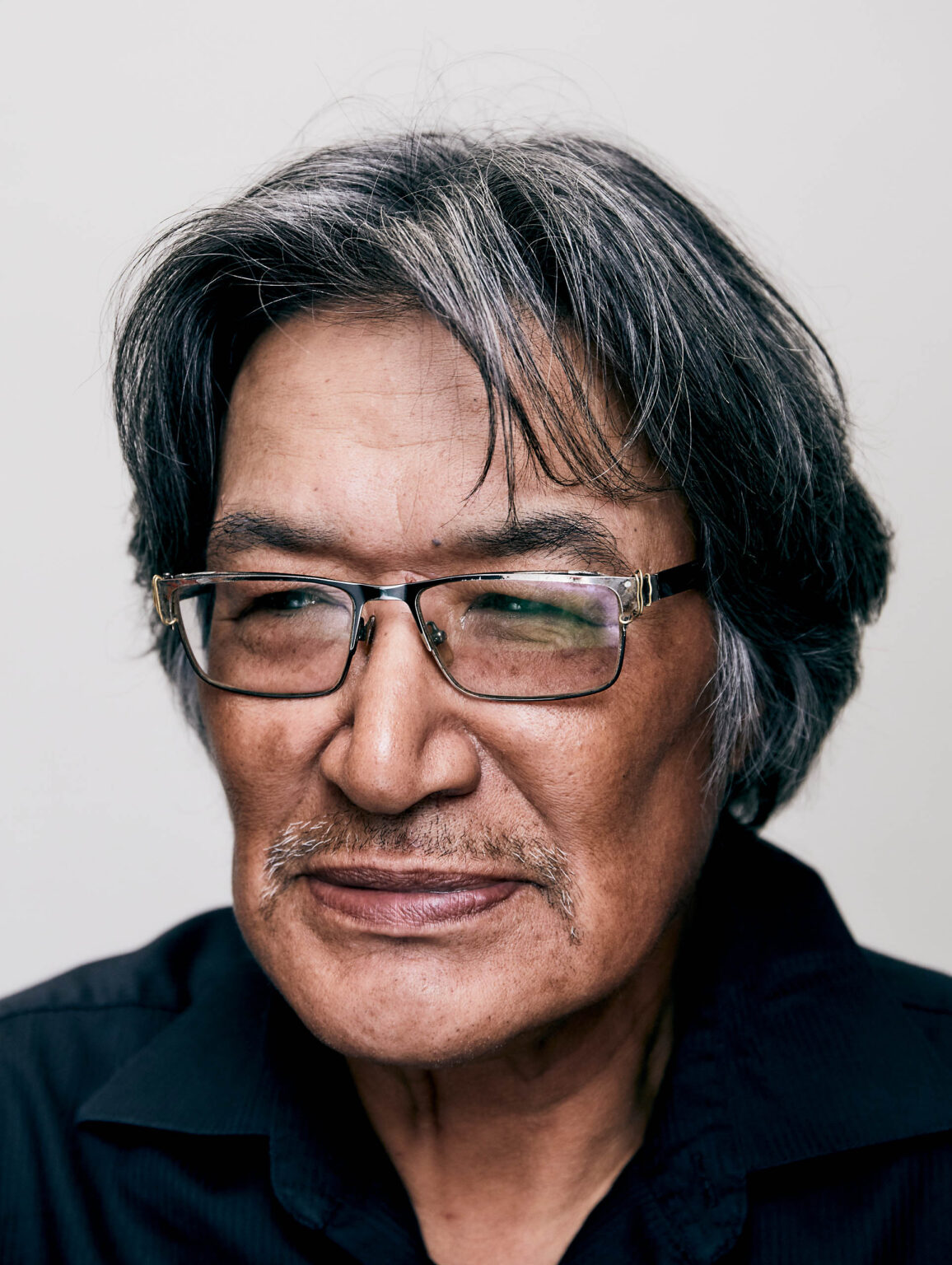

Photo by Luis Mora

Zacharias Kunuk on Carrying the Tradition of Inuit Storytelling Through Film

The award-winning filmmaker, who has dedicated his career to storytelling, has now created another poignant story of Arctic life with his latest tale for the big screen: Angakusajaujuq: The Shaman’s Apprentice. In this stop-motion animated short in Inuktitut with English subtitles, a young woman faces her first test as a healer and must visit Kannaaluk, the One Below, to help an injured young hunter while being guided by her grandmother. —Waheeda Harris

___

Photo by Andrew Querner

On Beauty and Violence With Dana Claxton

In her 30-year career, Claxton has amassed a multidisciplinary body of work as expansive as the sky. Exhibited globally, her art is centred on Indigenous narratives—told through film, photography, performance, and mixed-media installations—to challenge stereotypes and diagnose the symptoms of colonial legacies. “The core themes of my practice rest in ideas of spirit, land, social justice, and representation,” she says. Rooted in imagery of the Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux band, who followed Sitting Bull to Saskatchewan from the United States and from whom Claxton herself descends, Claxton’s work situates the Indigenous identity within contemporary contexts. —Ayesha Habib

___

Photo by Grant Harder

For Shawn Hunt, Tradition Is the Edge That Carves the Future

For Hunt, the forward movement is a synthesis of his personal expression and the deep connection he feels to his artistic lineage. “My thing has always been, I’m no different from my ancestors and that I’m just making art. It’s a part of my culture.”

Even though his work, with all its reference, asks for much reflection, Hunt’s been trying to focus more on emotions when creating, trusting the viewer to connect with the piece on their own terms. “They see what they see,” he says. “That, to me, is much, much more powerful than everybody seeing what I see.” —Ben Dreith

___

Charazo Back, watercolour on paper, 22.5 x 18.5”. Photo courtesy of Shane O’Brien and Gallery Jones.

Haida Artist Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas Challenges Conventional Readings of History

Born in 1954 and raised in a small fishing village in Haida Gwaii, Yahgulanaas describes himself as Haida by birth and Canadian by decree. With a Scottish father and an Indigenous mother, he embodies two identities often caught in ideological enmity. His maternal ancestors include master carver and painter Charles Edenshaw and revered weavers Isabella Edenshaw and Delores Churchill, so it follows that his aesthetic is firmly rooted in the Northwest Coast tradition of formline art, a pictorial style arranged around continuous curvilinear bands and ovoid shapes. —Rosie Prata

___

Photo by Lawrence Cortez

Sage Paul, Founder of Indigenous Fashion Arts, Is Cracking Open the Industry

Paul is the executive and artistic director of Indigenous Fashion Arts (IFA), which she helped create as a space for dozens of Indigenous-led brands to showcase their work, connecting them with both customers and businesses. Her CV includes orchestrating capsule collaborations between Indigenous labels and the Quebec retailer Simons, designing costumes for legendary Cree artist Kent Monkman, and creating and teaching an Indigenous fashion course for George Brown College. Various high-profile accolades include receiving the inaugural Changemaker Award from the Canadian Arts and Fashion Awards. —Caitlin Agnew

___

The First Nations Filmmaker Exploring Trauma, Remembrance, and Recovery

For Toronto-based director Sean Stiller, filmmaking is about more than artistic expression—it is a process of self-discovery. Stiller’s documentaries trace the lives of First Nations people, mostly in his home province of British Columbia, focusing on individuals whose lives form nexuses through which to view community and tradition and also the more impersonal but equally powerful forces of colonialism and environmental degradation that threaten deep-rooted ways of life. —Ben Dreith

___

A Sky Like You’ve Never Seen

Wilfred Buck is one of the world’s leading experts on Indigenous astronomy. In getting to that point, he experienced trauma and displacement in his early life in Manitoba, a story that may seem all too familiar for Indigenous people in Canada. He shaped his story into a memoir, the evocatively named I Have Lived Four Lives. Passages from this memoir serve as the narration for the dramatic portions of Lisa Jackson’s new documentary Wilfred Buck. —Jack Lowe

___

Shuvinai Ashoona Bridges Reality and Fantasy at the Vancouver Art Gallery

When Shuvinai Ashoona creates a piece of art, she lies on her stomach with a little pillow between her and large sheets of drawing paper. High heels are her shoes of choice while she works. She doesn’t sketch anything out beforehand; there is no preconceived idea. The drawings are plucked from her imagination with no filter of forced connotation.

Each piece melds Ashoona’s imaginative creations with visuals from her environment—influenced by the Northern terrain of Cape Dorset where she was born and Inuit iconography, as well as Western horror films, comic books, and television. —Ayesha Habib

___

Cheekbone Beauty: When Transformation Is Part of the Journey

Jenn Harper started Cheekbone Beauty in 2016 because she had a dream. “Sometimes I say that people interpret it as a vision because I’m Indigenous, but it was an actual dream—a crazy dream about all these Native girls covered in lip gloss, laughing. It was joyful,” Harper says.

Harper, who is Anishinaabe, had no background in beauty, but she did have curiosity, tenacity, and a desire to help other members of the Indigenous community. —Aileen Lalor

___

Brian Jungen artworks displayed at the AGO exhibition. Left: Friendship Centre, include Tarandus (blue), 2009, made of deerskin, raw-hide, braided sinew, and LED lights (photo by site photography. Courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jefferies, Vancouver. RBC Art Collection, Toronto). Middle: Prototype for New Understanding #4, 1998, made of Nike Air Jordans and human hair (photo by Trevor Mills. Courtesy of the artist and Catriona Jefferies, Vancouver). Right: Blanket no. 5, 2008, made of professional sports jerseys (photo courtesy of the artist and Casey Kaplan, New York). All artworks ©Brian Jungen.

The Artistic World of Brian Jungen

Jungen loves Air Jordans, although he doesn’t wear them himself. They wouldn’t fare well on the ranch near Vernon, B.C., where he has his studio, 10 head of Scottish Highland cattle, a few noisy chickens, and two horses, Cher and Mike.

“They became the iconic sneaker that everyone wanted,” Jungen says. “And they’re still like that.” To this day, when Jungen walks into a Nike store and buys 10 pairs, the salespeople don’t blink because they’re accustomed to collectors snapping them up to sell later at inflated prices. “I was interested in paralleling that with Native art and how Native art is bought and fetishized.” —Adrienne Tanner

___

Jenni Lessard Cultivates Creativity in Indigenous Cuisine at Wanuskewin

Lessard is the first female executive chef at Wanuskewin Heritage Park Authority, a centre just outside of Saskatoon that fosters education and respect for the land based on Indigenous culture, heritage, and arts. Wanuskewin is also on Canada’s tentative list for becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site, a first for Saskatchewan.

At Wanuskewin, Lessard combines her Métis heritage and her passion for local and foraged ingredients to create delicious cuisine for the centre’s restaurant, events, and catering services. —Naomi Hansen