The Origins of Makeup

More than a pretty face.

Do you ever wonder where something started? Why we are fascinated by vintage lipstick cases and jars? Well, they’re not cheap and disposable, or even frivolous—they’re artifacts, a part of history and a larger narrative surrounding cultural approaches to beauty.

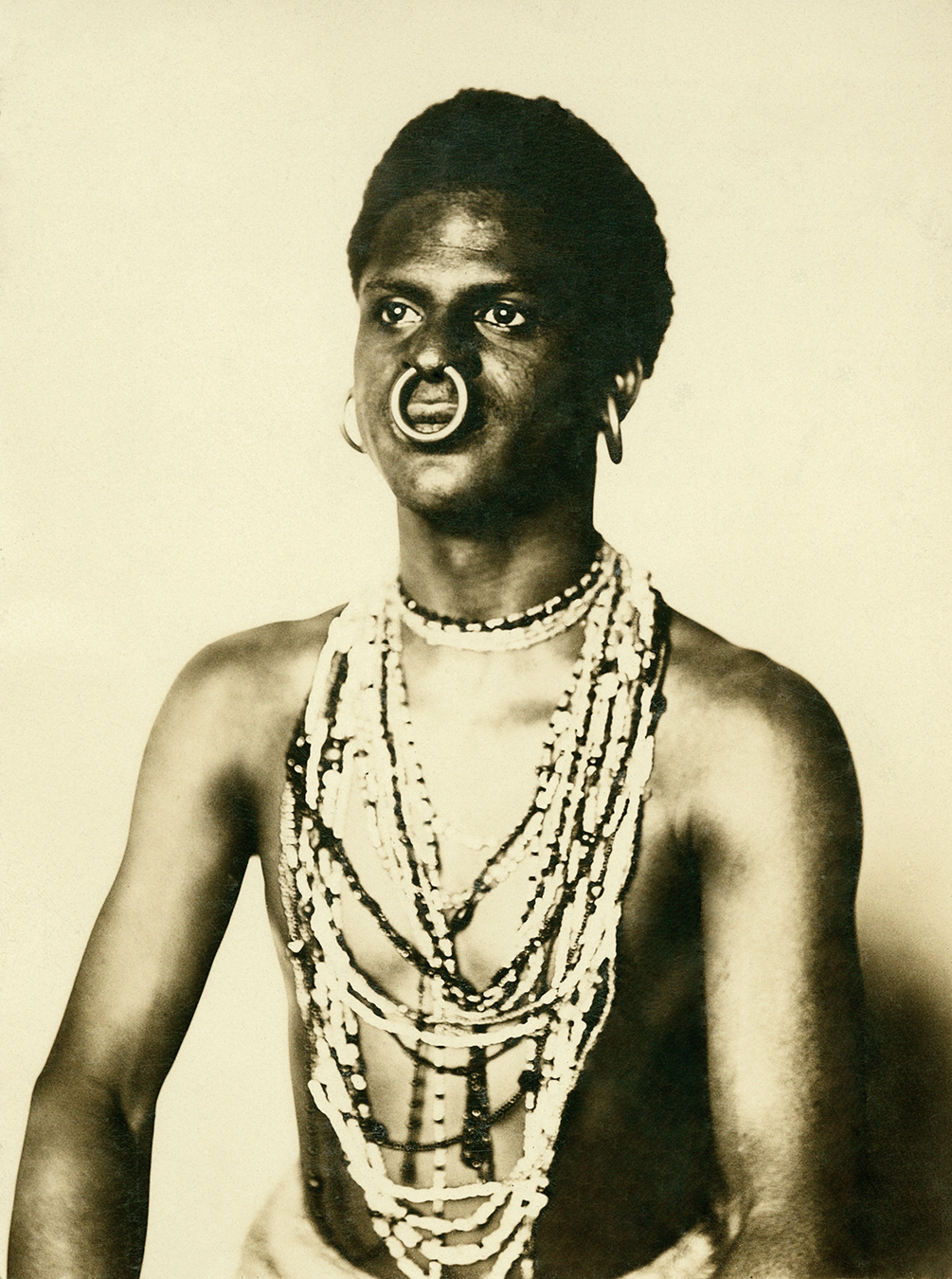

The art and ritual of painting one’s face, however, is of significance far beyond beautifying. Many African, Aborigine, and Indigenous cultures use face paint made from clay and coloured with dried plants and flowers to convey messages and values within their communities. It’s a form of language and symbolism separate from the North American Westerner’s perspective of makeup.

When considering the origin of cosmetics as we know them today, many argue that it was the Egyptians who first invented makeup—but as early as the first millennium BCE, Chinese royalty in the Zhou dynasty were using gelatin, beeswax, egg white, and gum arabic to paint their nails gold and silver. This practice continued for some time, and the nail colours eventually became a tool to identify social standing, as those in lower classes were forbidden from wearing bright colours.

There is also a story in Chinese culture surrounding a princess called Shouyang, that influenced makeup trends. Legend has it that she fell asleep under a plum tree, and a blossom fell and left petal stains on her forehead, enhancing her beauty. After her death, she was worshipped as the goddess of the plum blossom. This story is just one of the mythical origins of meihua zhuang or plum blossom makeup that gained popularity among courtly women during the Southern Dynasty from 420 to 589 CE. Women would decorate their foreheads with petals or paint florals using sorghum powder, gold powder, and jade.

A painting of princess Shouyang sleeping below a plum blossom tree.

Across 7,000 years of history, nearly every culture in the world has some mention or interpretation of cosmetics recognizable as the makeup we know today. But as romantic as the origin of makeup may seem—all painted clay pots and gold filagree compacts—the ingredients themselves were rather antediluvian. Clay, lead, ash, and burnt almonds were among the substances used as early as 3100 BCE to create the kohl cosmetic products for ancient civilizations in North Africa, India, and the Middle East.

The Egyptian rich and royalty, like Cleopatra, also had bright lipstick made from carmine beetles while the poorer citizens settled for clay to colour their lips. Both men and women Egyptians wore kohl eyeliner—but it wasn’t all about vanity. Heavily lined eyes were meant to protect against the evil eye and other spiritual dangers. It is believed that a lot of Egyptian beautification originated from rituals that honoured gods and goddesses, and warded off the elements. Incidentally, the eyeliner had a sunglasses-effect by deflecting the sun. The lead in the kohl also killed off bacteria and prevented infections.

Persians also used kohl, and after many converted to Islam, restrictions on cosmetics prohibited substances that were harmful to the body. Many practitioners took a medicinal approach to beauty, which is outlined in the 19th volume of Abu al-Qasim al-Zahrawi’s 10th-century medical encyclopedia.

Later, Greeks and Romans ground up stones to create the first-ever face powders; this trend, used to make skin as pale as possible, continued until the end of the 19th century. The strict codes of dress among upper-class women meant that only lower-class or sex workers used makeup to colour eyes, lips, and cheeks. As harsh as that sounds, the upper class had it worse because the lead-and-vinegar mixture that made up the ceruse face powders would cause hair loss, muscle paralysis, and even death.

A red makeup powder found in a tomb in Athens from 5th century BCE.

In Japan, geishas, kabuki actors, and other performers as early as the Heian period would also paint their skin as white as possible using shironuri makeup. The intent was to make them look beautiful when they were performing by candlelight.

Greek and Roman performers had no need for such makeup practices because they largely wore painted masks, and when they didn’t, they would wear sheep’s wool beards and colour their faces with lead- or flour-based paints. And contrary to the issues that the close-up Japanese performers had, in Europe the candlelit theatres meant crudity in makeup application passed unnoticed.

Innovations in lighting design that made actors’ faces more visible to audience members sparked a need for the first modern foundation. Greasepaint was invented by a German actor and made by combining lard with pigment, forming a stick that could be applied to the skin.

In the 20th century, a demand for commercially made and sold makeup as we know it began to emerge for several reasons including the invention of the camera, the affordability of mirrors, and the emergence of the starlet.

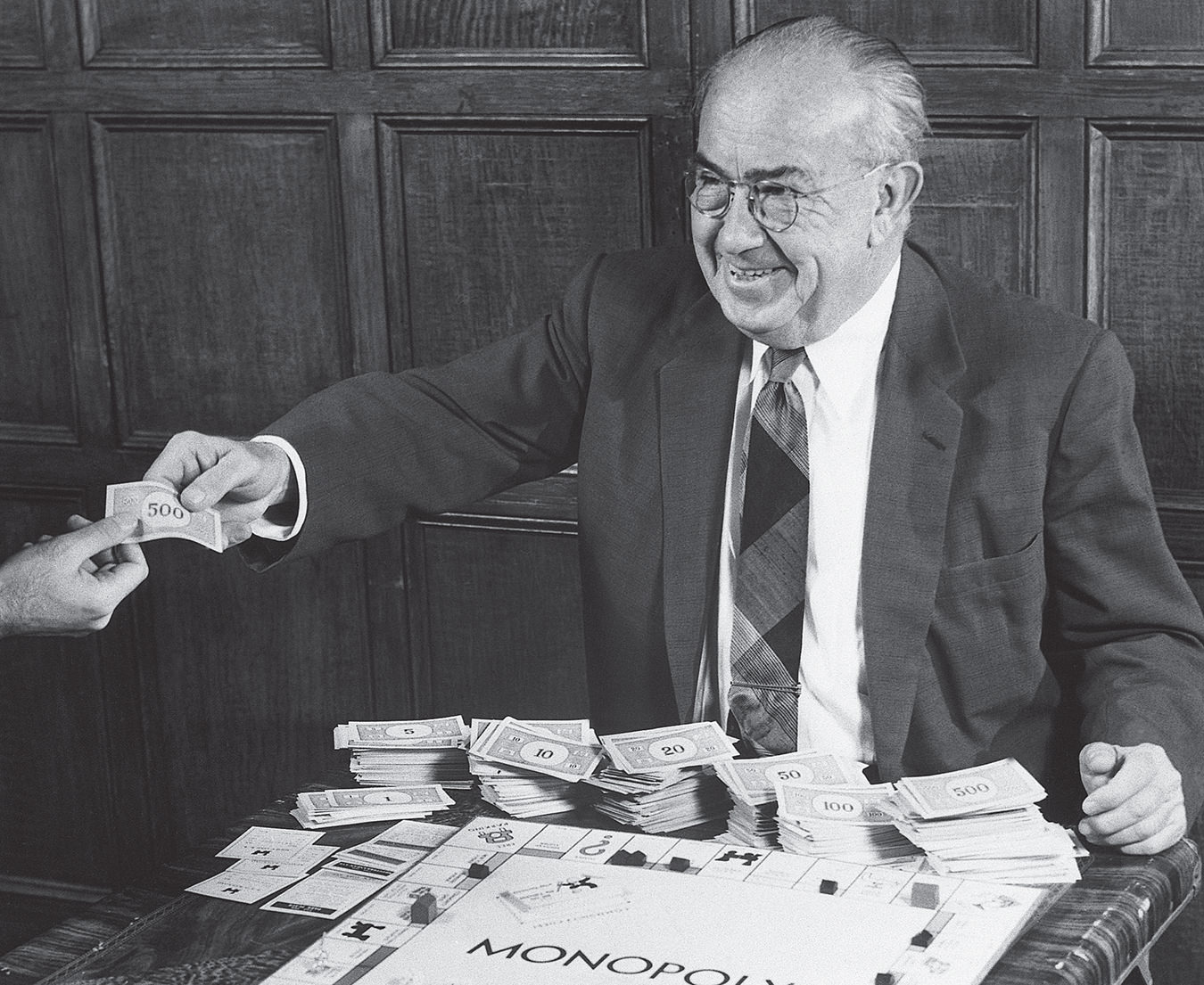

Portraiture and readily available mirrors in people’s homes made it necessary to look one’s best, but it was motion pictures that really tipped the scales. When stage makeup didn’t transfer very well to film (it was too thick), new innovations in the base were required. In 1914, Max Factor, the London-based cosmetics company that still exists today, took on the original greasepaint formula and created a semi-liquid version that could be stored in jars. Sales to to the public began in 1920. Maybelline first emerged in 1917 with a mascara made of petroleum jelly and coal dust that founder Thomas Williams invented for his sister Maybel. Companies that distilled pre-existing tricks for beautification into products and then sold them to the masses began to crop up, and rivalries and competition for women’s attention and money became part of the cultural zeitgeist.

A 1946 ad for Maybelline’s original cake mascara and their brow pencil and eyeshadow that was released out later.

Makeup and the cultural ideology surrounding it has come a long way, and we have seen several more peaks and valleys in interest since the beginning of the 20th century. In general, though, the formulations have drastically improved, and the fight for cruelty-free, vegan, clean beauty brands can only continue to benefit us and our health. There is also a mellowing on the horizon of this need to cover up and a growing desire to complement, instead. It is comforting to look back on the origins of makeup and its cultural significance to see that there is a purpose to the rituals outside of vanity and, hopefully, a clear path forward.

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.