Scalawags: Hugh D. McIntosh

A huge life.

Hugh D. McIntosh. His nickname summed up the man perfectly: Huge Deal. He made and lost fortunes time after time in his whirlwind of a life. Near the end of it, and not knowing he was near the end of it, the old rapscallion, who had promoted boxing matches and owned newspapers, theatres, and auditoriums, ran into some bad fortune but got back into the game by opening a chain of milk bars (corner stores) in London. “Hugh D.’s comeback was inevitable,” declared a tabloid newspaper back in McIntosh’s home country, Australia. “If he had not opened milk bars he would probably have made a fortune selling moustache cups to ballerinas or promoting an all-in wrestle between Hitler and the Archbishop of Canterbury.”

McIntosh was born in Sydney in 1876. When he was seven years old, Hughie, as he was called, asked his busy mother if he might go to faraway Adelaide with a grown-up man he knew. Her answer was a distracted yes. The man was a tinker, and he and the future Huge Deal went waltzing Matilda. When they reached Broken Hill, Hughie got a job separating ore from quartz at one of the mines. He held that for a year and a half when, not yet nine years old, he again went on the tramp.

McIntosh spent three years bumming around doing any job he could find. Back in Sydney, at age 12, he got work as an assistant to a doctor. His spare time was passed in a gym run by Larry Foley, an ex-fighter whom McIntosh referred to as “the man who taught Australia to fight”; the man also taught Huge Deal to fight.

The doctor died when McIntosh was 16, so once more he went roaming, working at dozens of jobs. In 1893, he appeared onstage in Melbourne as a chorus boy in Sinbad the Sailor. But his first financial success occurred in Sydney, where he proved to be a champion seller of meat pies, working the racecourses, boxing matches, beaches, and brothels. After his marriage in 1897 to Marion “May” Backhouse, a painting teacher, McIntosh took a job with a catering company as a pie delivery boy. Two years later, he was running the business. He also opened a physical culture hall and began managing his first professional boxers in 1900. He was 24 years old.

Also at this time, McIntosh was an aspiring bicycle racer. He eventually went on to promote races on a large scale. Following one event, after discovering that the riders had fixed the race, he stormed into the locker room and, in the words of a reporter, “laid out the guilty riders one at a time.”

In 1906, McIntosh sold his catering business and began investing in hotels and resorts across New South Wales. In December of that same year, he ran for a seat on Sydney’s city council. He lost and was taken to court by the winner. Charged with slander, McIntosh denied calling his opponent a thief, but admitted saying he was “a dirty, scurrilous, unmanly cur. And I still feel that way.”

A couple of years later, when a U.S. Fleet nicknamed the Great White Fleet, comprising 16,000 men, arrived, he knew his next fortune had come with them. He leased every available dancehall, restaurant, and theatre in Sydney. Then he got the idea for a fight, a heavyweight world championship bout. Toward this end, McIntosh, dressed like a bum, approached the owner of some leasable land at Rushcutters Bay and got the rights for £2 a week with an option to buy. In six weeks, he coordinated the building of what was then the largest boxing arena in the world—the old Sydney Stadium or, more affectionately, the Old Tin Shed—for the fight. McIntosh matched the Canadian champ Tommy Burns with Australian Bill Squires, and it was Australia’s first officially recognized world title fight.

His next fight promotion was not only his grandest, it is recognized by many as being the most significant contest of all time. McIntosh was able to match Burns with Jack Johnson, an African-American. It was the first time a black man had ever been permitted to challenge for the heavyweight championship, then regarded as the ultimate symbol of manhood. Burns originally had no intention of fighting Johnson, and when McIntosh approached him with the idea, he demanded £6,000, believing the amount to be an impossible fee. McIntosh agreed, essentially trapping Burns into the agreement. It was twice the highest amount that had ever been paid to a fighter.

Hugh D. McIntosh, nicknamed Huge Deal, was not solely a fight promoter. He bought several news and sporting papers; he staged serious plays; he promoted concerts; he travelled the world. In addition, he was a huge womanizer.

Posters for the fight between Burns and Johnson littered every Sydney street, which resulted in Hugh D. McIntosh finding the nickname that followed him throughout the rest of his life. On a Sydney tram, he overheard two drunks talking about the upcoming fight. “Ai, Bill,” one drunk asked his partner, “who is this huge D. McIntosh?”

On Boxing Day, 1908, the crowd that turned up for the fight was the largest ever to see a boxing match anywhere in the world. A few minutes before the bell for the first round, Johnson challenged McIntosh and demanded more money or he wouldn’t fight. Huge Deal reached into his jacket pocket and came up with a revolver, which he pointed at Johnson’s head. “If you’re not in the ring in two minutes,” he growled, “I’ll blow your brains all over the floor.”

Johnson entered the ring and McIntosh refereed the fight. The cops stopped the bout in the 14th round because the crowd was getting too rowdy, and as soon as word of the result went out over the wire, riots began. The heavyweight champion of the world was a black man.

The following year, Huge Deal took the two fighters on a circuit of vaudeville theatres, where they sparred with others and talked about the fight. He made a small fortune. Then he went around the world with the fight film. He made a large fortune.

McIntosh returned to Sydney in 1911 and expanded his promotions to include a Wild Australia show, carnivals, concerts, and eventually theatres. In 1912, he sold his Sydney Stadium to finance the purchase of the Tivoli Circuit. The takeover was big news, prompting Punch magazine to call him “the personification of the hustler” and “the kind of man who might have captained a pirate ship.”

McIntosh bought all sorts of acts for his theatres, from ragtime piano players to playlets by George Bernard Shaw, and he employed future stars like W.C. Fields. He introduced the tango to Australia with his series of tango teas: patrons would sip tea while dancers in scandalous outfits performed the Argentine dance. When in London to scout entertainers, McIntosh was asked to vacate his suite at the Savoy because he had covered the walls with Tivoli posters. Not wanting to leave, McIntosh formulated a scheme and sent a generic letter to the King discussing the funding of British sports. Before he could pack, a letter came for him bearing the return address of Buckingham Palace. The official-looking envelope merely contained a polite acknowledgement of the receipt of his original letter, but those at the Savoy were none the wiser. McIntosh suddenly became a favoured guest.

McIntosh was unstoppable, at least for another decade and a half. In 1916, he bought several news and sporting papers; he tried to organize McIntosh’s Rough Riders during the First World War; he staged serious plays; he promoted concerts; he travelled the world; and he generally continued making vast sums of money. In addition, Huge Deal was a huge womanizer. One of his stage managers declared that “he’d go through anything with long hair on it.”

Between 1921 and 1929, McIntosh divided his time between his Sydney mansion and a manor house with 243 hectares near Canterbury that he leased, which was the former stately home of Lord Kitchener. He associated with all manner of people from all strata of society. Some of these were rough customers. McIntosh kept a piece of sheet music on his desk rolled to conceal a lead pipe, which he was not averse to using. Artist Norman Lindsay remembers that the tune that wrapped the pipe was a lullaby titled “Sing Me to Sleep, Mother.”

He gave money to hospitals and charities, persuaded the government to organize the installation of the cenotaph at Martin Place in downtown Sydney, and hosted innumerable parties and receptions. He socialized with Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells, Rudolph Valentino and Charlie Chaplin. Then two things happened: the invention of talkies and the worldwide stock market crash. First he sold The Sunday Times. His other papers soon followed, and then the interests that leased his theatres went bankrupt. He fled to his estate in England and turned a corner of his property into a model farm raising angora rabbits. Nobody came to the new plays he produced in England because movie tickets were a quarter of the price. By 1932, he was bankrupt. He sold his grand home in Australia and moved with his wife into a cottage in Sydney.

But this was far from the end of Huge Deal. Suddenly he was successful again, as the operator of the Tivoli Sponge Bakery, making sponge cakes. Success, however, ruined the business, as it attracted many imitators with more capital.

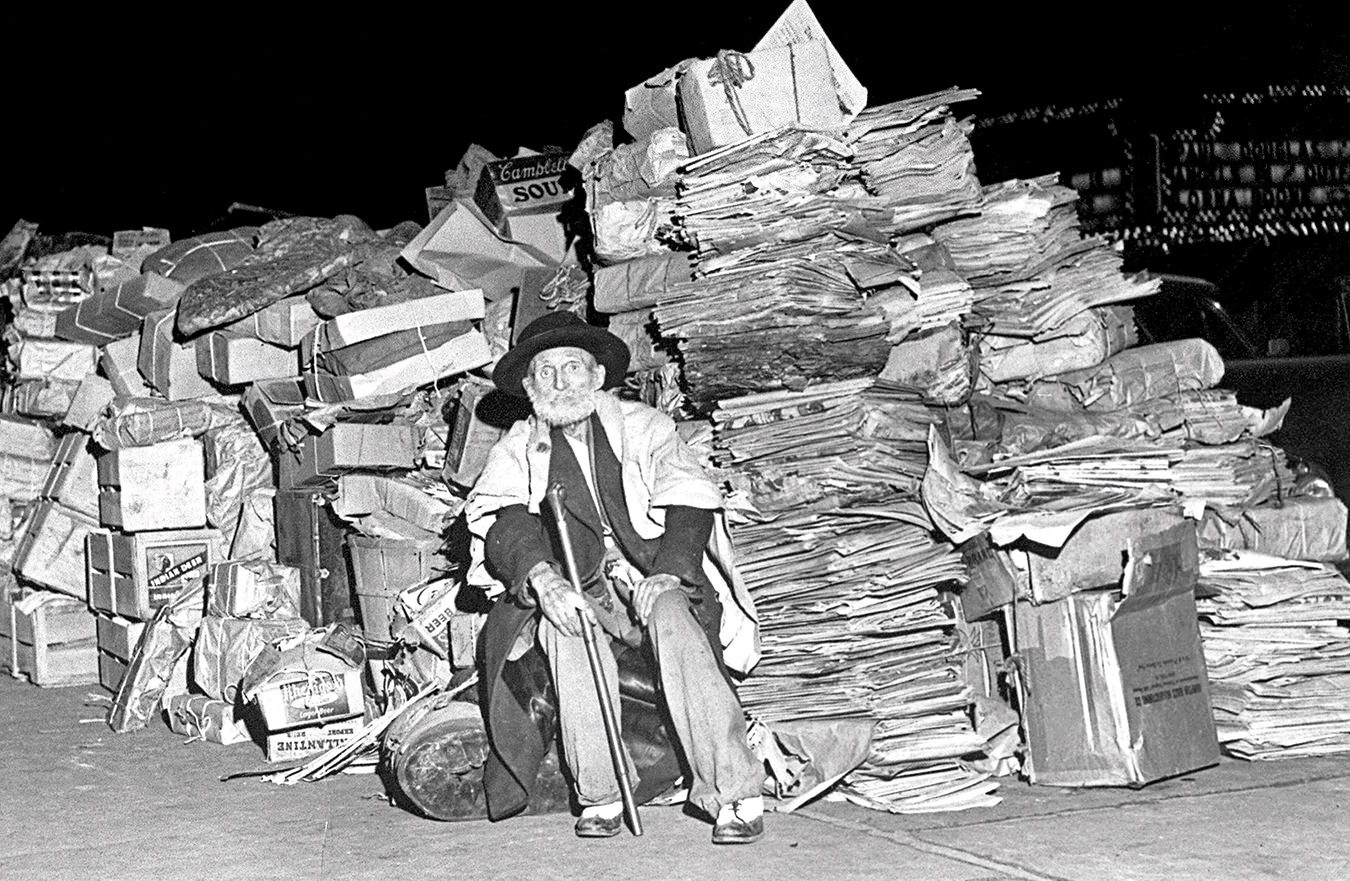

McIntosh briefly got back into boxing and made some money, but not enough to begin to pay his creditors. Next he took a job managing a guest house in the Blue Mountains. When the year was out, in 1934, he left Australia for the last time, travelling third-class with his wife to England. Within a few months, he had picked himself up yet again and was running a successful milk bar. Soon there was a second, a third, and eventually 20 Black and White milk bars throughout the country. But as with the Tivoli Sponge Bakery, competition laid him low.

McIntosh entered the timber business just as war was declared in 1939. The next year he served as inspiration for the character of a social-climbing hustler who owned a boxing stadium in the Australian film Come Up Smiling. The year after that, he was diagnosed with colon cancer. He died in London on February 2, 1942, at the age of 65. At the end, he had only £2 to his name. Friends paid for his cremation.

A lot of men fancy themselves hustlers and entrepreneurs, pulling off vast projects by brains or energy or chicanery—but, in comparison, they are only little deals. There has only been one Huge Deal.