The Salzburg Festival Turns 100

High note.

The aim of the festival, as founding director Max Reinhardt once described, was to bring people together through music and drama, “to escape the chaos of the times.”

There’s an old joke that’s told among musicians: a violinist arrives as a new recruit to the Celestial Orchestra, and is dumbstruck. “What an amazing orchestra!” he exclaims to St. Peter. “Heifetz leading the violins, Casals leading the cellos… But that old man conducting—he’s terrible! Who is he?” “Oh,” replies St. Peter. “That’s God. But he thinks he’s von Karajan.”

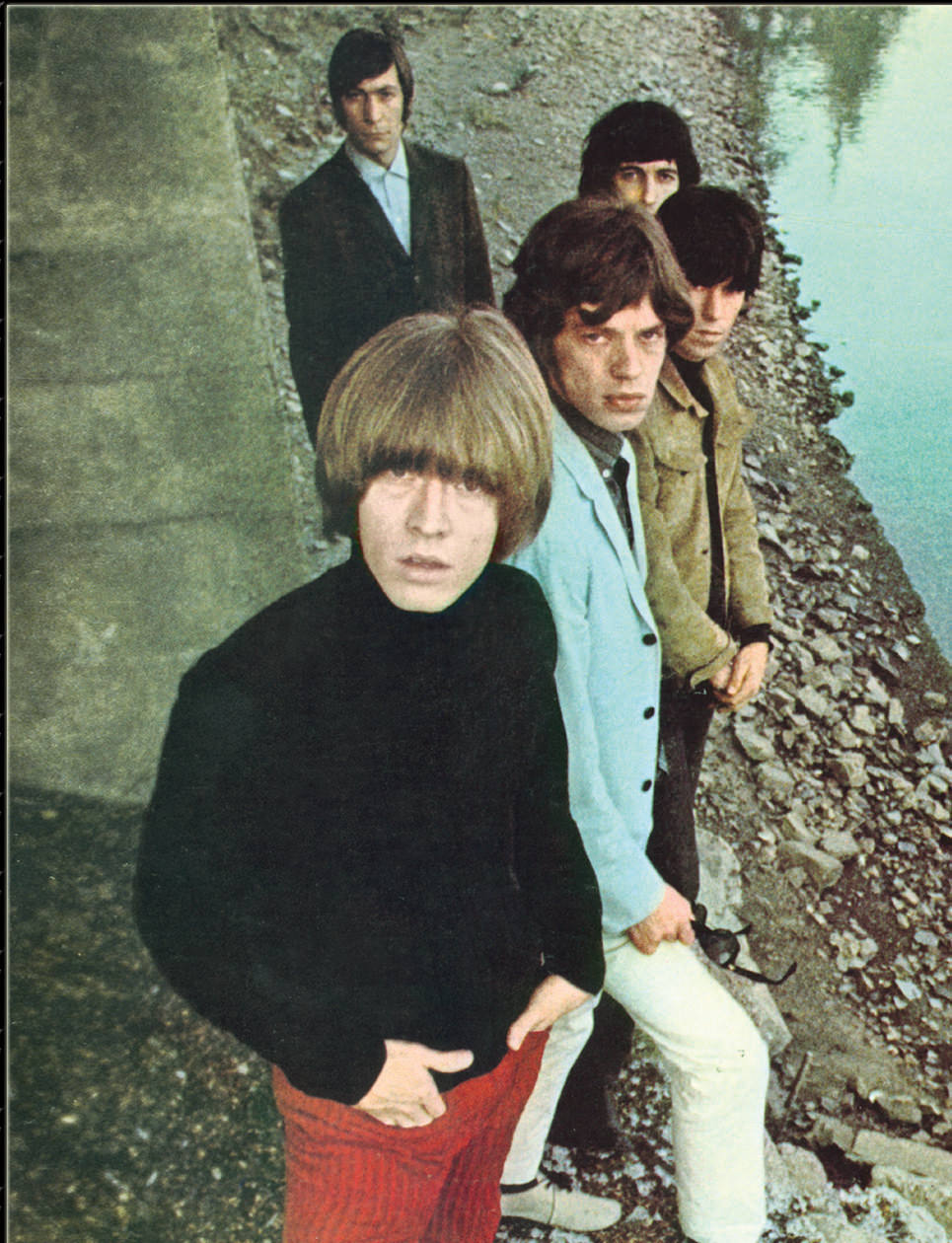

From the 1950s until his death in 1989, Salzburg-born Herbert von Karajan was arguably the most famous conductor in the world, dominating the music scene with his twin powerhouses—the Berlin Philharmonic and the Salzburg Festival. Karajan, who was known as much for his racy lifestyle—fast cars, yachts, and jets—as for his music making, was also reviled for his early links with the Nazi party and his autocratic tendencies. This was the era in which members of the bejewelled international jet set, who might otherwise not have set foot in an opera house, flocked to the maestro’s performances in Salzburg like iron filings to a magnet. The most dedicated groupies stayed at the Hotel Friesacher, close to his home in the nearby village of Anif, hoping some stardust might waft their way. Even today, many associate the Salzburg Festival with Karajan.

Yet the roots of the festival, which turns 100 this year and runs from July 18 to August 30, were nurtured in very different soil. Founded in the aftermath of the First World War by the intellectual triumvirate of theatre director Max Reinhardt, dramatist Hugo von Hofmannsthal, and composer Richard Strauss, the aim was to bring people together through music and drama, “To escape the chaos of the times,” as Reinhardt once described. Salzburg, according to him, was “far from the distractions of a big city,” and the trio’s ideal venue—a world capital of the arts. In the wood-panelled library of Schloss Leopoldskron—a former palace Reinhardt had purchased in 1918—the festival began to take shape.

Jedermann [Everyman], written by Hofmannsthal.

The choice of play to launch the festival on August 22, 1920, was pointed. Jedermann [Everyman], written by Hofmannsthal based on an English Protestant morality play and directed by Reinhardt—both men were Jewish—was a sensation. This annual summer festival has since blossomed into over 200 opera, concert, and theatre events held at various venues throughout the city during its six-week period, with Jedermann a constant, reprised in an open-air theatre in front of the cathedral each year.

“Are you here for The Sound of Music?” my guide, Sabine, asks wearily when we meet in the so-called New Town on Makartplatz. On one side of the street is the house Mozart’s family moved to when the composer was 17; on the other, the Mirabell Palace and Gardens, one of myriad pilgrimage sites in Salzburg for fans of the film—Maria and the von Trapp children sang “Do-Re-Mi” around its Pegasus fountain. Sabine brightens considerably when I state that this is not why I am here. “Would you believe,” she says, “that 300,000 people a year come to Salzburg only to see locations from the film? They are not interested that Mirabell Palace was built by Prince-Archbishop Wolf Dietrich von Raitenau in 1606 for his mistress, by whom he had 15 children—let alone that the Mozart family performed [at the palace].”

Salzburg’s baroque architecture—which includes the cathedral—planted amid the medieval streets, narrow-fronted houses, and forts of the Old Town, owes its existence to the prince-archbishops. We pass the famous Hotel Sacher, formerly the Österreichischer Hof and one of the first luxury hotels in the city, with its rogues’ gallery of actors and musicians—it is the place to see and be seen during the festival. We cross the Salzach River, which separates the 19th-century New Town from the Old, arriving in the Domplatz. We are in time to hear the 35 bells in the tower of the New Residence chime a minuet from Don Giovanni. “The bells were brought by horse and carriage from Antwerp in a three-week journey in 1695,” says Sabine. “The melodies change, but the times of the carillon remain constant: 7 a.m., 11 a.m., and 6 p.m. every day.”

Orphee Aux Enfers play.

In this quarter of baroque purity, there are other constants: a 430-year-old pharmacy, and the Stiftsbäckerei St. Peter, a 12th-century bakery, with its reconstructed waterwheel and wood-fired ovens that entice passersby with an irresistible whiff of fresh sourdough bread. An atmospheric cemetery where Mozart’s sister, Maria Anna—endearingly called Nannerl—is buried leads to St. Peter’s Abbey, to which the bakery once belonged. Next door, St. Peter Stiftskulinarium, where Charlemagne is said to have lodged, lays claim to being the oldest inn in Europe. First mentioned in the historical record in the year 803, today it is a labyrinthine restaurant of cozy nooks and crannies that is known for its traditional fare.

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was born on the medieval Getreidegasse in 1756, is the city’s most famous son. Mozart remains the most performed composer at the festival. A 1781 quarrel between the irreverent composer and his early patron, Prince-Archbishop Hieronymus von Colloredo, would see Mozart decamp to Vienna. He returned two years later to the abbey church of St. Peter’s to premiere his (unfinished) Great Mass in C minor with his wife, Constanze, as soloist. That the Salzburgers were less than flattering towards her was the last straw, and Mozart broke with his native city.

But Salzburg’s musical foundations had been laid, and the Salzburg Festival has become the city’s driving force. “The Salzburg Festival represents 100 years of European cultural history,” states artistic director Markus Hinterhäuser. “But it is not enough to look back. It is important to lead the festival into a new present.”

Jedermann [Everyman], written by Hofmannsthal based on an English Protestant morality play and directed by Reinhardt.

For the centenary program, Hinterhäuser has balanced homage to the past with a modernist aesthetic and avant-garde stagings. Among the new opera productions are Strauss’ Elektra, a work that brought together the three festival founders; and Mozart’s Don Giovanni—the first opera performed at the festival, under the baton of Strauss in 1922. These operas, characterized by the excesses of the individual, are counterbalanced by others with the theme of society, as represented by Modest Mussorgsky’s Boris Godunov and Luigi Nono’s Intolleranza 1960. “It is a cliché that the Salzburg audiences are conservative,” insists Hinterhäuser. “Things are changing. I know of no other festival audience so generous in its response to contemporary music.”

The festival has a tradition of championing young artists. Among those making their way over the hallowed cobbles this year will be Lithuanian soprano Aušrine Stundyte (Elektra) and Greek firebrand conductor Teodor Currentzis (Don Giovanni). More familiar names include Cecilia Bartoli (in Don Pasquale, which in 1925 was the first non-Mozart opera to be performed here), Plácido Domingo (I Vespri Siciliani), and Tosca, with Anna Netrebko in the title role and her husband, Yusif Eyvazov, playing Cavaradossi.

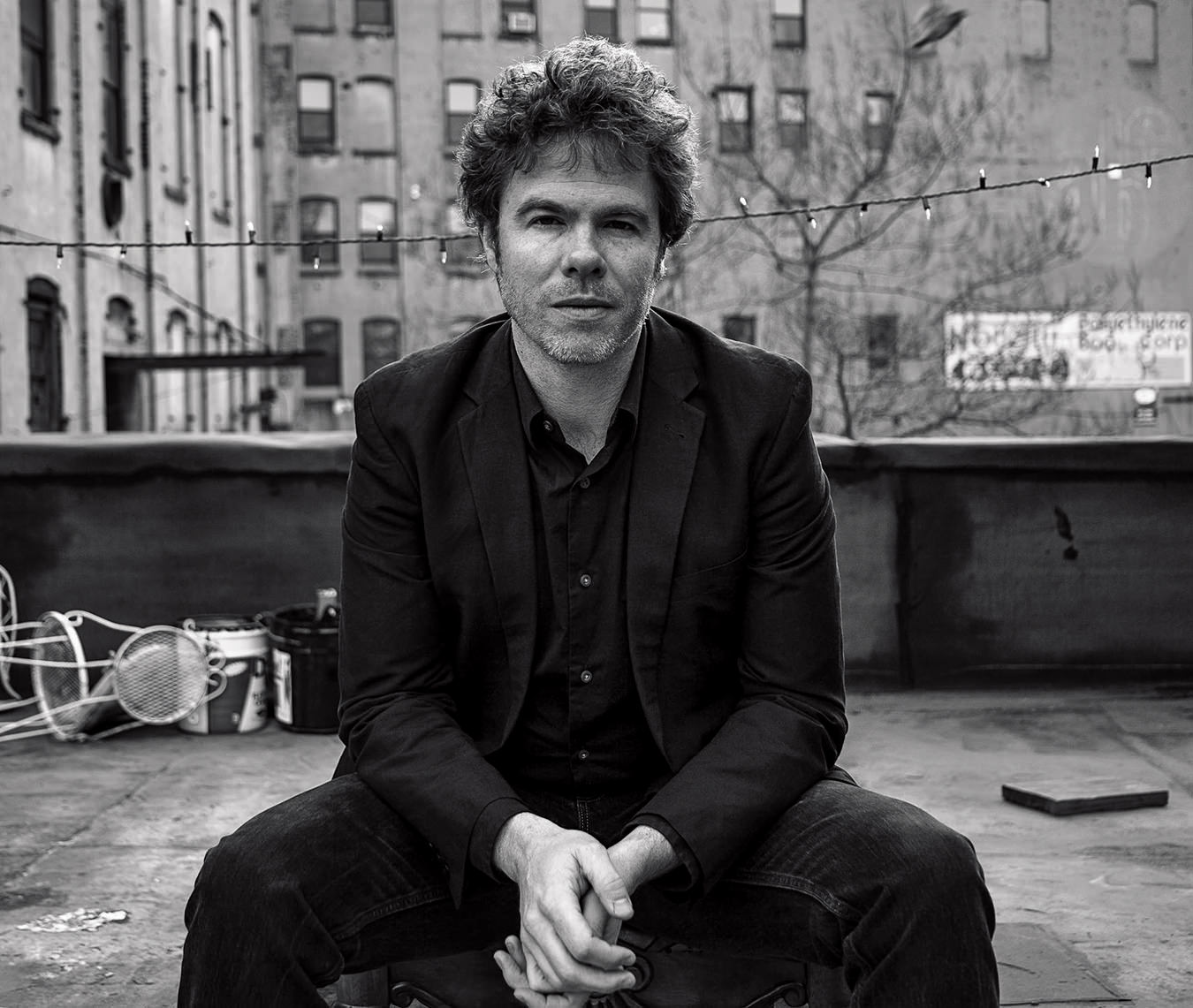

Out of the 91 notable concerts and starry recitals taking place, the cycle of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, played by phenomenal young pianist Igor Levit, promises to be a highlight. Levit—“One of the most fascinating and important musicians of the new generation,” says Hinterhäuser—will perform this tour de force over eight evenings, marking the composer’s 250th anniversary.

One thing is certain. In this city of music, whatever happens at the festival is the talk of the town. “In Salzburg,” says Hinterhäuser, “even taxi drivers will discuss programs with you.”

________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.