La Vida Colombia

Out of the shadows.

The historic La Candelaria neighbourhood of Bogotá. Photo by Katie Nanton.

Safety first. That is always the rule when heading to a foreign land (although it’s not one that I’ve always heeded). When my plane takes off for Bogotá, the Spanish-speaking elderly lady on my left signs the cross. After we hit the tarmac in Colombia, the young woman to my right does the same. Surrounded by this protective bubble, I’ve almost never felt so safe on a plane—let alone on the ground in a country once deemed far too dangerous for travellers.

“Ninety per cent of the country can now be visited,” says Fabio Quiroz, my guide while in Bogotá, assuaging any lingering fears on my first day in the cool capital city. (Here, everybody tends to carry an umbrella in September, as they do in June. The city’s location on a 2,650-metre-tall plateau is part of the reason for its 15ºC year-round median temperature; they know no seasons.) Taking to the streets, we walk up some of the steep San Francisco–like hills of La Candelaria, the historic and cultural core of the city that was named a national monument in 1963.

“Before the Spanish arrived, this was a spiritual spot where people came to a lake and performed spiritual ceremonies,” Quiroz explains as we come upon Plaza del Chorro Quevedo. According to historical accounts, this was the very place where Bogotá was founded. Today, there is no lake in sight, but there are teenagers splayed upon steps, studying textbooks. Farther downtown is Bolívar Square, where the perplexing human desire to feed the pigeons is in full force—only here there is a rare juxtaposition of llamas lazing in the sun.

“Bogotá is known by two colours primarily: the red of the brick and the green of the mountains,” says Quiroz. These are joined by gold at Bogotá’s expansive Museo del Oro (Gold Museum), which houses the Banco de la República’s collection of more than 50,000 shimmering pre-Colombian gold pieces. Originally founded in 1939, the museum recently reopened in 2010, and proudly displays gold-plated conch shells and gilded breastplates with cosmological signs etched into their surfaces. These sit alongside everyday objects turned extravagant with the Midas touch, like gold tweezers and fish hooks. For all that the conquistadores took in the days of pillage and plunder, the museum seems to overflow with gold. “Fortunately, the Spanish couldn’t take it all,” says Quiroz. “They left some so we could do business.”

The past few years have seen travellers flocking back to a territory once considered a no man’s land for foreigners. Colombia is undergoing a present-day architectural and urban revitalization on a very visceral level.

It was those Spanish who found another of the country’s sparkling natural resources in the form of emerald mines; almost 70 per cent of the world’s emeralds come from Colombia. Far less glamorous but also sought-after, another delicacy forms underground here: salt. An hour’s drive north of Bogotá is the Salt Cathedral of Zipaquirá, a twisting network of underground caves that were once working salt mines and later opened to the public. I overcome claustrophobia to stroll deep underground and am confronted with a multitude of large crosses, carved out of salt, that appear backlit by soft lights in their own vignettes: the 14 small chapels representing the Stations of the Cross. Farther still into the caverns is a choir pit and a 16-metre high cross, which has the thrilling distinction of being the largest underground carved cross in the world. After almost an hour of walking inside this mountain, I feel released from purgatory as I step outside into the fresh air.

There seems no better time to fly headfirst into heaven, so the next day I take to the skies and travel north to Medellín, the second-largest city in Colombia. It is here that I encounter a man who wants to save my life. He limps through traffic wearing a bright red T-shirt at the crux of 10th avenue and 43rd street with his hands waving through the air and eyes stern. His name might not be widely known by locals, but he is. “He was hit by a car on this corner, years ago,” explains Daniel Álvarez, my guide to these unfamiliar roads. “Now he’s always here directing traffic because he doesn’t want it to happen to anybody else. Sometimes he holds a hand out for money, but you don’t have to give him anything—he does it because he wants to do it, every day.”

The past few years have seen travellers flocking back to a territory once considered a no man’s land for foreigners. Colombia is undergoing a present-day architectural and urban revitalization on a very visceral level. It is most pronounced in Medellín.

The city was, in the late 1970s and ’80s, the epicentre of Pablo Escobar’s drug cartel. The narco-trafficking fallout led to ongoing internal conflict that was only accentuated by the drug lord’s death in 1993. Today, numerous public spaces are being created through city policy measures, many of which were initiated by Sergio Fajardo—the charismatic mayor who held office from 2004 until 2007—and continue under the current mayor, Aníbal Gaviria. Communities are becoming connected, allowing real change to flow through the city. Like other destinations that have been touched by tumult in the not-so-distant past, it seems as if everybody has a six-degrees-of-separation story to someone who has fallen to cartel crossfire. To say that, in those days, Colombia truly was dangerous was undoubtedly fact. Today, Medellín’s streets no longer hold the clear and present danger that they once did; far from it.

Early morning is the best time to visit the pinnacle of the city, before the workday rush begins. Take the metrocable gondola ride up 2,072 metres of Medellín’s mountainside. The three gondola lines were completed in 2010 and connect the outer slums with the bustling city, making it one of the most significant emblems of social change in town. The fee is also government-subsidized for locals. It glides over the labyrinthine streets as it climbs, the expansive city basin opening up below. The dwellings are built closely together, but the streets are as clean as the buildings are colourful.

The voyage up has three stops, the second of which is in the Comuna 13 neighbourhood, where three onyx-black structures sit like rocks: this is Biblioteca España, built by Colombian architect Gian Carlo Mazzanti in 2007. Comuna 13 was notoriously one of the city’s most impoverished areas a decade ago, but you wouldn’t know it today. One room of the library is filled with schoolchildren working diligently on computers; in another, a group watches the environmental documentary An Inconvenient Truth while weaving old plastic bags into bracelets and ornaments.

Farther up the metrocable lies Parque Arví, the last stop and a favoured hiking destination full of dense, protected forest. At its mountaintop market, I sample fresh fruit juices while plump abuelas spoon out dollops of creamy arequipe dessert for passersby to taste. A man with a gelatinous mixture in a vat by his feet is spinning a doughy concoction in the air like a cat’s cradle. We converse in broken English and I add “homemade marshmallows” to my Spanish vocabulary list.

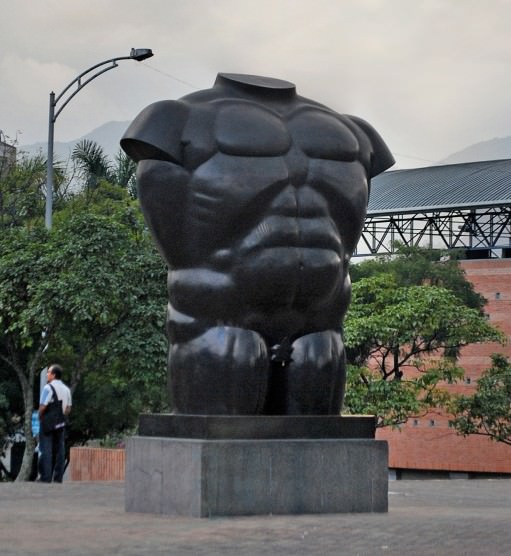

Fernando Botero’s Torso Masculino Desnudo at Parque San Antonio in Medellín.

I travel back down the hill to another revitalized part of town: Jardín Botánico, recreated as a botanical garden in 1972 from its previous state as a bathhouse. An oasis in the centre of town, the garden contains the modern Orquideorama, an architectural marvel of interconnected honeycombed modular structures, designed by architects Felipe Mesa and Alexander Bernal. Eight years ago, nobody would walk through this area unless by necessity. Today, lunching ladies and well-dressed business people dine on salads of cured cow tongue with green papaya, and fish and chips with fresh lime, at In Situ, the gardens’ restaurant, before strolling through the rambling grounds.

The metrocable gondola in Medellín connects the outer slums with the bustling city, making it one of the most significant emblems of social change in town.

Colombia’s transformation is unmistakably happening from the inside out. It is for the people who live here, first, and for visitors, second. Groups of young, educated entrepreneurs who had left Colombia have returned. Víctor Saldarriaga is one such individual; he tends shop at La Sierpe, a jewellery store that wouldn’t look out of place in Brooklyn. “I’ve lived all over—in New York, even in Vancouver,” he says. “But I’m back for good now.”

As the sun descends on my last day, there is probably no better place to visit than one of the city’s oldest graveyards. The Cemetery of San Lorenzo is now used for Edgar Allan Poe readings, open-air cinema screenings, and live performances. It is yet another sign that Medellín is not covering up history but regenerating critical, cultural thought. There is a desire to form connections between the present and the past, proving just how far the infrastructure has developed.

The last stop of the day is Parque San Antonio—not on our regular schedule but it’s a place I’ve been curious about. As I walk up the steps of the parking lot–like square, one of the public artworks by Colombian artist Fernando Botero appears before me: Torso Masculino Desnudo (Nude Male Torso). On the far end of the square sit two more sculptures. One is a voluptuous dove, Pájaro de Paz (Bird of Peace), perched up on its haunches. The second is but a scarred remnant of his robust brother. It is a tragic sight, not only to see one of the artist’s distinct larger-than-life depictions all hollowed out, but for what it stands for. It is symbolic of the loss of life that occurred when a guerilla group detonated a bomb underneath the sculpture in 1995 that killed 23 bystanders.

The Medellín-born artist agreed to cast another grand sculpture to replace the injured piece, on one condition: that the old version remain on display as a reminder of the ugliness of warfare. Speckled shadows fall around the melted bird as a trio of young boys climb inside, at play within a past that is behind them.

All photos, except Gondola photo, by Katie Nanton.