The BMW Art Car idea was born in 1975. Race-car driver Hervé Poulain was interested in establishing a link between the worlds of art and racing, and approached BMW with the idea of working with an artist to alter the appearance of his BMW 480 hp 3.0 CSL. The car company welcomed the idea, and Poulain’s friend Alexander Calder was commissioned to design the art for the automobile. Since that first creative endeavour, BMW has established a collection of 16 Art Cars by prominent artists including David Hockney, Jenny Holzer, Roy Lichtenstein, Frank Stella, Robert Rauschenberg and Andy Warhol—each making a unique statement about the appearance and meaning of cars in our time.

That statement, these days, is admittedly very different than in years past. Driving a car has long been considered an individual activity: you can go where you want without restraint, in an act of transportation liberation. But recently, environmental concerns have become paramount. Due to climate change and our anticipation of its potentially disastrous consequences, the focus is now on environmental awareness.

So when internationally acclaimed Danish-Icelandic artist Olafur Eliasson accepted BMW’s commission to create a BMW Art Car based on the hydrogen-powered H2R model, he wanted to take a slightly different approach. “The project would not revolve around the car as object,” he says of his plan for the Art Car. “Rather, it would be the point of departure for inquiries into form development, temporality, individual and collective mobility, as well as environmental concerns.”

The H2R, which has the look of a futuristic race car, is a research vehicle. It has a 12-cylinder, six-litre engine that can accelerate from 0 to 100 kilometres an hour in around six seconds, achieving a top speed of over 300 kilometres an hour. The hydrogen-combustion engine is based on the petrol-drive power unit featured in the BMW 760i. BMW has been researching the use of hydrogen for more than 25 years, and has established numerous records for hydrogen-powered vehicles featuring a combustion engine.

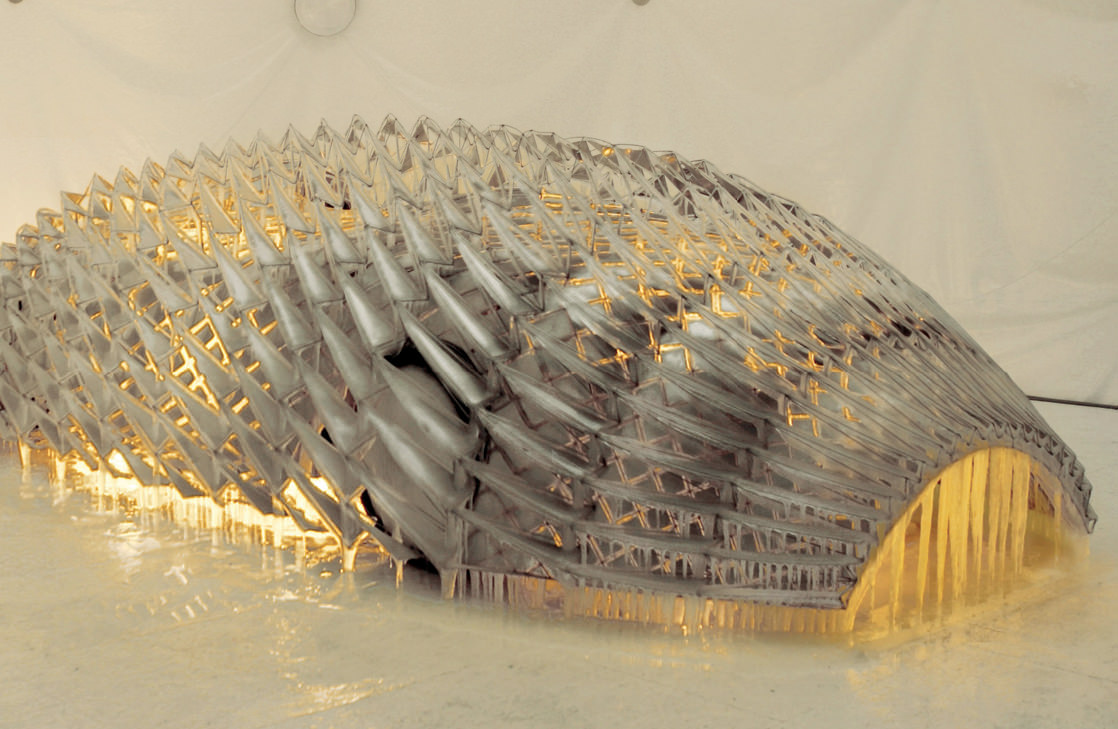

For his take on the Art Car, which he titled “Your mobile expectations”, Eliasson removed the outer covering of the H2R and replaced it with a complex skin of metal that envelopes the body of the car, which was then covered with a fragile skin of ice. The exposed frame was sprayed with some 2,000 litres of water to gradually produce the intricate frozen layers. It celebrated its premiere at the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich this summer, where the vehicle was exhibited in the museum in a –10ºC freezer to preserve the car’s ice coating; guests could go right into the freezer to see it, and were provided with blankets.

Eliasson worked on the H2R project for over three years, and talked to a range of BMW Group personnel, including Chris Bangle, director of group design, and his team, as well as engineers and others who deal with mobility and sustainability. “I’m interested in how we connect with our surrounding world,” says Eliasson. “My artistic practice isn’t about this or that object; it’s a laboratory process. So, a car might initially seem a very odd thing to engage with, but I’m extremely interested in mobility and our understanding of time and movement. … I think movement is intimately linked with our way of perceiving the world. It emphasizes the physicality of our being; it connects our bodies and brains.” The car’s ice-covered cocoon is intended to dissect the relationship between car production and global warming. As a work of art, Eliasson’s transformation of the H2R is a design provocation that opens up debate about the impact of art and design in a contemporary social setting.

Notably, the automobile doesn’t have a BMW logo—which is quite the statement in an industry in which importance is placed on corporate identity. Does the lack of logo matter? “No,” says Thomas Girst, spokesperson of cultural communications for BMW Group. “What is important is that Olafur Eliasson tackled the subject and was interested in dealing with mobility and dealing with hydrogen as a renewable energy source, and that is what I think matters. The idea of the race car is still there.”

With his H2R project, Eliasson has challenged us to think not just about the way we move, but about the status of movement. “A car takes us from point A to point B, but it is the space in between—the movement—which defines. What does that journey represent?” That’s an all-too-relevant question we should be asking ourselves, and one implicit in Eliasson’s frozen creation.