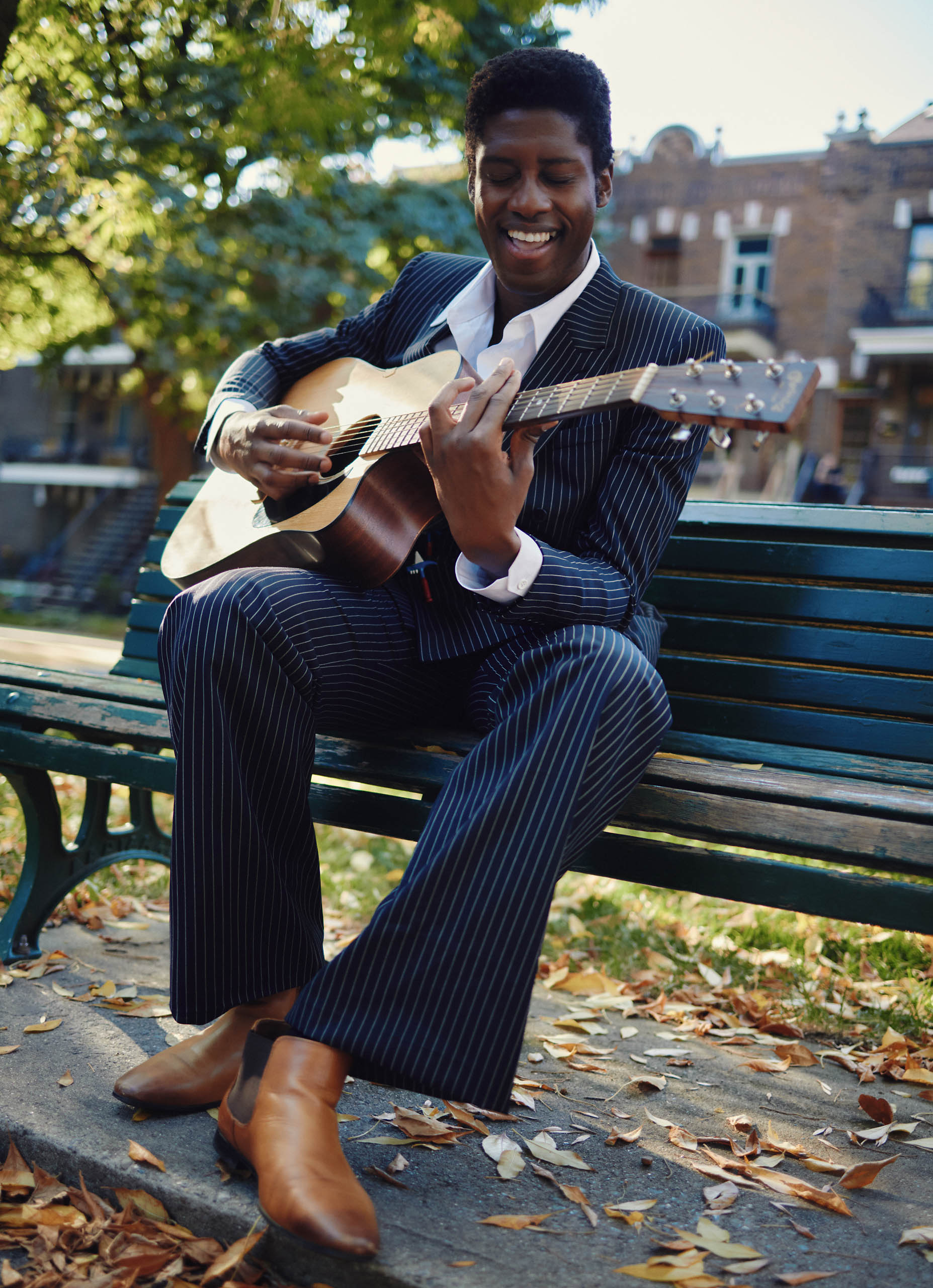

Louis Vuitton look.

Smooth Like Butter

Take a trip through Clerel’s gliding vocals and soul-stirring beats.

In the infinite stretches of imagination, even the smallest of moments can trigger sweeping possibilities. For Clerel Djamen, inspiration can strike as he’s walking down the street, where the sounds of construction work—the bangs and clanks of objects being moved, the rhythmic whirring of a machine—come to him like a song. Without realizing it, he’s singing along to the cacophony of the world, finding melody in its chaos. “A lot of times, I’m humming something before even noticing. I had to learn to stop and say, ‘Oh, where does that come from? I like that,’ ” the soul singer, who goes by his first name on stage, tells me from his home in Montreal.

Louis Vuitton look; boots Clerel’s own worn throughout.

_

It’s strange to look at Clerel, a man who emanates the suave coolness inherent to blues and soul singers, and think he could be anything other than an artist. As he performs, leaning slightly back and plucking away at the strings of his guitar, his Sam Cooke–inspired voice flowing out of him, he looks at home. Precisely where he should be. Yet if fate had twisted a little differently, this artist could have ended up a chemist.

An affinity for music has always been instinctive, a type of knee-jerk reaction he never thought twice about. From the Cameroonian music he grew up with in Douala—singers like Francis Bebey and Manu Dibango—to the contemporary Top 40 R&B of the 1990s and 2000s, song and rhythm were formative companions throughout his youth. He unknowingly developed his vocal talent by singing church hymns as a child, but the thought of actually being a musician simply didn’t click in until he was an adult.

“I feel like sadness or longing is one of the most innate human traits. Sometimes you don’t even know what you’re longing for. And for me, soul music was a partial answer to that in the sense of being able to express that yearning.”

—Clerel

Fendi look.

That revelation came when he was a pre-med chemistry student in the States, where his family had immigrated to after Clerel finished high school. A serendipitous trip to the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis sparked a love affair with the genre for Clerel. He became swept up with the sounds of icons like Otis Redding and Marvin Gaye and soon after, picked up a guitar for the first time. His roommate taught him chord progressions, and slowly, in the pockets of time after class, Clerel progressed song by song.

Still, it wasn’t until he moved to Montreal after graduating university in 2013 that he even contemplated performing in front of an audience—spurred more than anything by the idea of meeting people in his new city. “I went to an open mic, and honestly, that was the best decision,” he says. “That’s basically where I met all the other musicians in town, how I heard about other open mics, other jam sessions.”

Hermès look.

Bottega Veneta blazer and pants available at Holt Renfrew; Hugo Boss turtleneck.

The rest, as they say, is history. After a stint leading a double life—a “grown-up” job during the day, jam sessions and live shows at night—Clerel jumped head first into his art, quit his job, and became a musician full time. “I figured it would either go really bad or work really well, but either way, I didn’t want to get to a point where I look back and say, ‘Ah, man, I should have done that,’ ” he says.

And today, with an EP, several singles, festival appearances, and a performance on The Late Show with Stephen Colbert under his belt, Clerel is not looking back with regret. His songs—sung in English as well as his native French—are detailed with bouncy guitar lines and smooth-like-butter vocals. Yet, for all its sonic flourishes and upbeat tempos, Clerel’s music is deceptively melancholy; a closer listen reveals his lyrical tendency toward nostalgia and heartbreak. It makes sense, though, when we remember that an urgent affinity for American soul music was the catalyst for his art to begin with.

Louis Vuitton look.

“I feel like sadness or longing is one of the most innate human traits,” he says. “Sometimes you don’t even know what you’re longing for. And for me, soul music was a partial answer to that in the sense of being able to express that yearning.”

“Blackstone,” the song of choice for his Late Show appearance and by far his most popular single yet, exists in a sort of contradicting space of emotion. The song is made up of major chord progressions—sounds primarily associated with happiness—while the lyrics lament a love lost with lines like: “Well, time will help us cauterize the open wounds.”

But, Clerel explains, those happy-sounding major chord progressions are actually quite melancholic to him. “I don’t know if it’s because I grew up listening to [major chords] in a different light in Cameroon,” he wonders out loud, sharing how these sounds stir up childhood memories and evoke a sense of nostalgia and vulnerability for him. Conversely, he tells me, he finds minor chord progressions, typically the sad-sounding chords, to be “the fun ones.”

Ermenegildo Zegna look.

Gucci look.

Hugo Boss look.

Perhaps it’s a side effect of learning music as an adult. He’s yet to be influenced by the conventions and boundaries of music theory, which has allowed him to make music purely from an emotional space while drawing from his personal histories both lyrically and sonically. Indeed, he tells me that songwriting is like a continual process of therapy to understand himself and the world around him. The emotions that can be hardest to convey with simple words, he translates to melody. And in that bittersweet mix of happy and sad lies a purity of emotion that, like Clerel’s inherent artistry, cannot be denied.