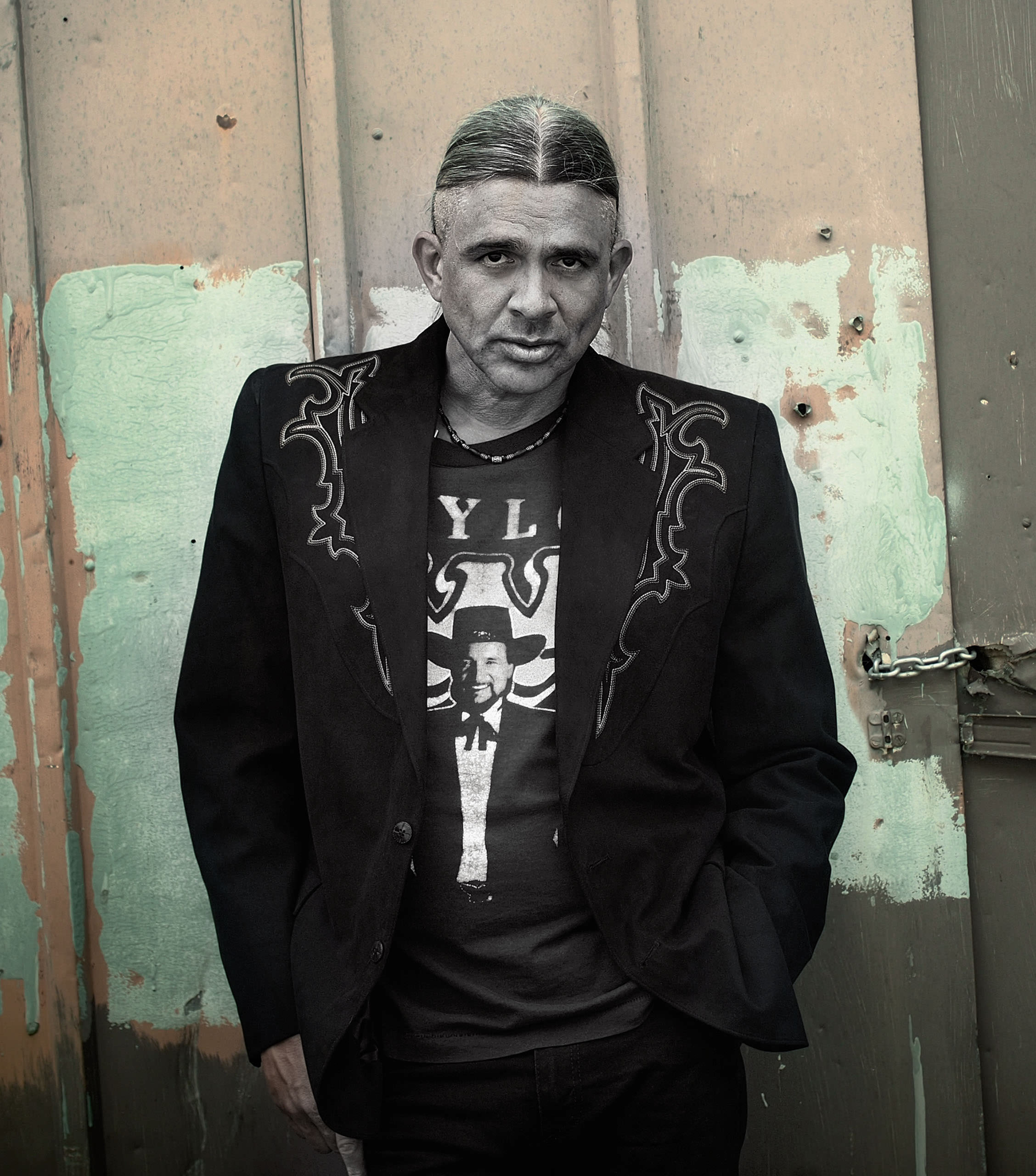

Stephen Graham Jones Battles Stereotypes and Serial Killers in His Breakout Novel

The perils of being a good Indian.

Stephen Graham Jones, member of the Blackfeet Nation, is an athlete of the printed word, often localizing common slasher tropes in the context of Indigeneity.

Stephen Graham Jones approaches writing as if he’s going to battle. Even over video conference call, Jones beams a level of hyperfocused energy normally associated with Navy SEALs. He cracks his neck, Bond-villain style, several times during our interview, and I’m not surprised to learn that he types with such force he regularly wears out his computer keyboards. Jones is not your typical desk-jockey author—he is an athlete of the printed word.

“I’ve heard other writers say that their sock drawer is never so organized as when they’re writing a novel,” he says from his home in Boulder, Colorado, where he is the Ineva Reilly Baldwin Endowed Chair Professor of English. “Which is to say, when they’re writing a novel, they’re looking for other things to do. I’ve never had that issue. When I’m writing a novel, the sock drawer is not organized, the lawn is not mowed, and the oil in the truck is not changed. I don’t like doing those things. I like writing.”

If Jones’ output is anything to go by, that sock drawer must be messy, indeed. Since his debut novel, The Fast Red Road: A Plainsong, landed in 2000, Jones has published over 15 novels in a dizzying array of genres: horror, western, science fiction, crime, thriller, and experimental literary fiction. Then there are the 250-plus short stories to his credit and too many comic books, essays, and think pieces to count.

Given Jones’ love of his vocation, he’d have been happy to keep hewing to the path of a Great Writer You’ve Probably Never Heard Of, his name a byword for innovative but fan-friendly fiction among genre nerds and academics (University of New Mexico Press published a book on his work in 2016).

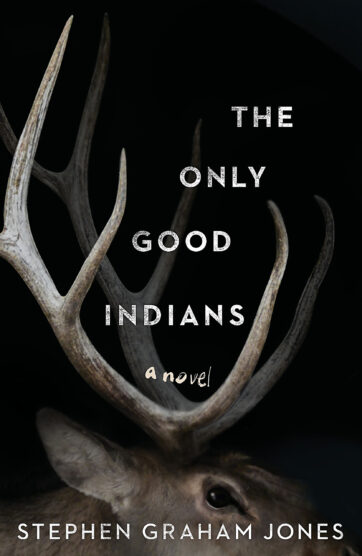

No one could accuse Jones of being apolitical or disengaged. Like all his work, The Only Good Indians, for all of its laugh-out-loud humour and pop-culture savvy, is a testament to the survival of Indigenous peoples and the threats that shadow their daily lives.

Then 2020 happened. In July, Jones released The Only Good Indians, the story of four friends living on and around the Blackfeet reservation in Montana pursued by a vengeful spirit. Jones is a member of the Blackfeet Nation and has always written from that point of view, peopling his work with a wide array of Blackfeet characters. But with Black Lives Matter protests forcing America to face its collective racial sins, the culture finally caught up to Jones.

Before the novel hit the stands, The Only Good Indians was already garnering comparisons to Jordan Peele’s Get Out as a cultural touchstone for this race-charged historical moment. Preorders, online and print reviews, and word-of-mouth buzz pushed the book into a second printing before the drop date, and since publication, the novel has gone into a fourth print run, attracting rave reviews.

If Jones is fazed by the intrusion of next-level success into the author’s cloistered world, he doesn’t show it. Warrior-like focus aside, Jones is personable, soft-spoken, and quick to laugh, and he shrugs off the spectacular praise for The Only Good Indians with a shrug, as if he’s slightly embarrassed by the attention, chalking it up to good luck in his laconic Texas accent. He laughs when I ask about the accent. “My granddad met my grandma up in Fort Belknap, Montana, where she had just left the reservation to go to typing school,” he explains. “He was in the air force, and after they were married, they gallivanted around the bases. When he retired, they just happened to be in West Texas.”

Jones grew up in a small West Texas town, barely a dot on the map. There he played basketball for the local high-school team (the sport figures prominently in The Only Good Indians) and cultivated his love of genre fiction and horror and action movies from the local video outlet. His parents were often short of money, leading at times to a hardscrabble existence. “Money was the big concern in my family growing up. We worried about the rental place hauling away the furniture again.”

Reading provided a necessary escape and point of focus for the restless youth. “An uncle of mine showed [me] his library,” Jones says. “It was mostly paperback westerns. He also had all the Conan the Barbarian books. Living in a small town, to be able to imagine a place like Conan’s Hyperborea—it was so transportive. Then I got into Stephen King. I would go into the bookstore and see all those horror paperback covers—man, every one of them looked good.”

By the time he entered grad school in his 20s, he was already imagining a future as a writer. But for a kid from a sleepy Texas town who’d cut his literary teeth on a diet of westerns, space operas, and Friday the 13th movie novelizations, the school’s reading list—heavy on experimental, postmodern fiction—was a shock.

“When I came to grad school, it felt like a betrayal of the stuff I’d grown up reading. So the deal I made with myself was: you can go to grad school, but you have to be in ninja mode. Go in and steal the good craft and smuggle it back out to science fiction and western and horror. But when I was introduced to Thomas Pynchon and John Barth, all these authors who push the edges of story and narrative, I just fell into the whole of them.”

Jones’ first published book was, as he puts it bluntly, his version of a Thomas Pynchon novel, but he was already working on several genre projects, one of which evolved into his debut horror novel, Demon Theory (2006). He never looked back. Though he still writes in several genres, horror remains his primary focus. Which brings us full circle to The Only Good Indians, a riveting take on the iconic 1980s horror subgenre, the slasher (think Freddy Krueger of Nightmare on Elm Street fame). The novel follows four middle-aged friends who, in a fit of testosterone-inspired bravado 10 years earlier, shot up a herd elk on a patch of Blackfeet reservation land set aside for the nation’s elders. Amongst the victims is a pregnant elk cow so infuriated by the hunters’ violation of sacred tradition that she returns to wreak vengeance, taking the form of an entity known as Elk Head Woman.

Jones has revitalized the slasher’s hoary tropes with a decidedly local twist—Elk Head Woman has got to be the first supernatural elk serial killer—but the novel’s title points at the work’s deeper intentions. As Jones has observed in interviews, the title is taken from a remark attributed to then soon-to-be U.S. president Teddy Roosevelt, who opined that “the only good Indians are the dead Indians.” But the reference is more than an indictment of the genocidal campaign against Native American peoples and the ongoing racism faced by the survivors.

Jones insists that the only way forward for him is to continue bringing a complex vision of humanity to the page.

“I am trying to push back against both definitions of the ‘good Indian,’ the white version and the traditional,” Jones explains. “And the ones I’m pushing most hard against are the in-community standards and stereotypes that you’re supposed to fit into as an Indian. Lewis [one of the novel’s protagonists] is an example. He identifies himself for a long time with being a good hunter. He’s still adhering to an old notion of what it means to be an Indian. But there’s so many good ways to be one.”

Jones isn’t sure how that message will be received within the Indigenous community. “From what I’ve heard, a lot of people are saying, ‘Yes, I’m going through the same thing.’ As an artist, that trap is still set in the culture, that if your character is not the default—that is, not white—the question becomes, when is that Indianness going to activate?”

Indianness, as Jones wrote in a much-discussed essay, is not a superpower that the hero reveals in the movie or novel’s final act. “You’re born Indian, you die Indian, and you’re Indian pretty much the whole way through, except maybe at Halloween, when other people get to buy a costume of you.”

No one could accuse Jones of being apolitical or disengaged. Like all his work, The Only Good Indians, for all of its laugh-out-loud humour and pop-culture savvy, is a testament to the survival of Indigenous peoples and the threats that shadow their daily lives. “I’ve been in situations—with the police, for instance—where I know how [being Blackfeet] can play out, how it wants to play out.”

Jones insists that the only way forward for him is to continue bringing a complex vision of humanity to the page. “In this climate,” he says, “when I write fiction, my attention tends to go to real people. In order to do real people, I have to do nuanced depictions of race, sexuality, gender. The character has to be real or the reader won’t care about them … Of course, I wonder sometimes, should I be writing or should I be marching in the streets with a sign? How can I best contribute? That’s an important question.”

Jones recently released his second book of 2020, Night of the Mannequins, a novella that also turns the slasher subgenre on its head. He is currently writing a comic for Marvel’s new Indigenous Voices series, as well as a feature film script and teleplay that he is “not allowed to talk about.” He recently completed another novel—yes, it is a slasher—and has several projects in various states of completion.

“I will always choose to write over everything but my family and my health,” Jones says. “When I come to my desk or to my keyboard, wherever my keyboard is, I feel like I’m hiding from the world and playing with dragons.” His new and old readers will no doubt be waiting to rejoin him there.

Photos provided by Simon & Schuster.