Jennifer Abbott’s Lamentation for a Dying Planet

The grief of climate change.

_________

It’s snowing in July. Flakes float almost tenderly to the forest floor—a false sense of serenity that contrasts a more violent truth. Looking closer, it’s not snow at all but ash from a nearby forest fire along British Columbia’s coast. This is the opening shot of Jennifer Abbott’s Magnitude of All Things, one of the filmmaker’s latest projects and her most personal to date. The documentary, about the psychological effects of climate change, was catalyzed by the singular moment when Abbott mistook ash for snow—re-enacted in the film—and recognized the heaviness that weighed down on her: grief.

“For the first time, I identified grief as something that I was experiencing in relation to the loss of the world around us as we know it. I think the reason I could identify it so quickly is because I had experienced the loss of my sister,” Abbott says. The grief she felt that day as ash fell down on her was “similar in tenor but different in intensity” to the emotions she felt after losing her sister Saille to cancer in 2008. “Along with that realization came the subsequent exploration of the psychological and emotional dimensions of the climate crisis,” she says.

The Magnitude of All Things, which premiered at VIFF this fall and was co-produced by the National Film Board of Canada, is a story about this interconnectedness of grief, weaving together Abbott’s personal narrative of losing her sister and the narrative of various communities around the world affected by the loss of their lands, homes, and identities to climate change. But the film is not another urgent plea to save the planet while there’s still time—at least not in a direct sense. It’s a softer, poetic meditation on loss, an invitation to sit with the, at times overwhelming, emotional toll the world feels in an age of rampant information consumption.

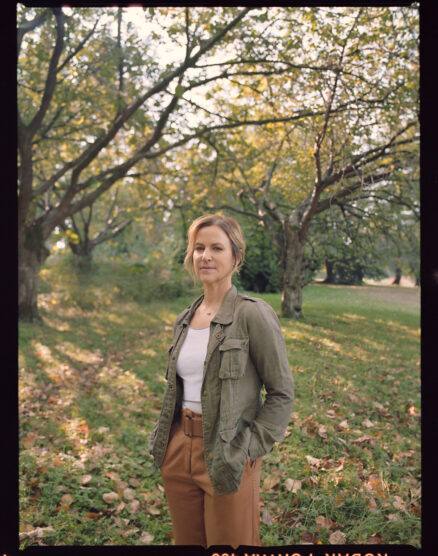

Director Jennifer Abbott in Labrador, Canada, during a shoot for The Magnitude of All Things. Photo by Stasia Garraway.

Loss is a universal intangibility; we all know how it feels to have a vacancy where something we loved used to be. The Magnitude of All Things contextualizes this loss in an environmental sense.

Loss is a universal intangibility; we all know how it feels to have a vacancy where something we loved used to be. The emptiness that follows is at once an individual experience and a collective sensation. Abbott’s film contextualizes this loss in an environmental sense: fires burn across swaths of land in Australia, glaciers melt away Indigenous ways of life in Nunatsiavut, and Amazonian forests are torn apart for their resources.

As a writer, director, and editor, Abbott has made a career out of creating documentaries about pressing social and environmental issues. “I’ve been very political and involved in social justice issues for really as long as I can remember,” the Montreal-born, Vancouver-based filmmaker says. After earning a degree in political science at McGill, with a focus on radical political thought and women’s studies, Abbott flirted with pursuing law to become a human or animal rights lawyer. Three days into law school, however, she dropped out to study film at Emily Carr University of Art and Design, instead. Film and documentaries, she found, carried a certain cultural power to “change hearts and minds and, by extension, the world.” Influenced by the likes of The Thin Blue Line director Errol Morris, Abbott sought filmmaking as a route to “work against injustice in its evolving and dynamic forms.”

Two years into studying at Emily Carr, Abbott decided to drop out and self-learn instead, (she would return to teach at the school years later). Subscribing to a do-it-yourself mentality—fittingly, she both directs and edits almost all of her films—Abbott figured she didn’t need school to make them on her own. Her first documentary, A Cow at My Table, which she completed in 1998, is an insight into the struggle between the meat industry and animal rights advocates.

But perhaps Abbott’s most famous credit is as the co-director of 2003’s documentary The Corporation, based on the book by UBC law professor Joel Bakan. Often referred to as one of Canada’s best documentaries, The Corporation is a massive undertaking of the capitalist status quo. The film asks a simple question: if a publically traded corporation were a person, what type of person would it be? Over nearly three hours, it supplies the answer through interviews with academics and political activists to diagnose the corporation as a psychopath, demonstrating the ways it influences and controls much of our lives with no remorse for the adverse consequences. “That film was a monster of a film,” Abbott says, citing almost 400 hours of raw footage she edited herself over two years. “When you’re making a film about the corporation, which has its tentacles almost everywhere, it’s more what you do not include as opposed to what you include.”

Through personal letters from her sister, Abbott grants us insight into the revelations her sister made on death while living with a terminal illness and how they can be connected to the way we approach climate change.

Aftermath of the bushfires in Australia.

In a testament to the times, the film’s sequel The New Corporation, aptly subtitled The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel, premiered at TIFF this year. Bakan and Abbott worked together again, this time putting into question the true nature of “socially conscious” corporations. “He made the realization that corporations were trying to look like they were cleaning up their act, but really what they were doing was making themselves more superficially charming,” she explains. “At the same time, every problem that we addressed in the first [film] is getting worse.”

If The New Corporation is the academic essay detailing the cause and effect of capitalist greed, then The Magnitude of All Things is the poem that laments the aftermath of that greed: climate change and its manifestations around the globe. With sweeping cinematography, philosophical dialogue, and re-enactments of her childhood experiences with her sister (played by Abbott’s own twin daughters), she describes Magnitude as a hybrid between narrative and documentary. Through personal letters from her sister, Abbott grants us insight into the revelations her sister made on death while living with a terminal illness and how they can be connected to the way we approach climate change.

“Culturally, most of us aren’t that willing to face our mortality—it’s something we understandably compartmentalize. And the same is true of climate change. The scale and violence of it is just so much [for] most of us, including myself. It’s overwhelming,” she says. “When my sister died, she was just such a beautiful model for walking this line between wanting to live and fighting to live but on the other hand surrendering to her death. She understood that that was the only way she could live a conscious, kind of whole death, if you will … Because my sister was able to face her deepest fears and sorrows, she actually knew in her death she could teach me about life. And because I had the great privilege of witnessing that, I thought, ‘Yes, of course, we have to do that with climate change.’ We have to go towards our deepest fears and sorrows. If we turn away, we’re not going to see what’s coming in our direction. We’ve got to go towards it, we’ve got to accept it.”

Accepting the inevitability of death, and similarly accepting the reality of climate change, is not a route to complacency, Abbott argues. Instead, she offers an almost radical perspective that it is the concept of hope that placates. “As filmmakers, we are pressured to make hopeful films, and it’s my belief that hope can be a form of denial itself. If you have hope, it’s not necessarily the best motivation to get you to change your life radically, make sacrifices, or take action. I’m not saying everybody should lose hope,” she quickly adds. “I think hope is not what we think it is, it’s a complicated dynamic. Maybe you’re depressed, you get a little hope, then you act. Or maybe you lose hope and then you act,” she explains, referencing that climate activist Greta Thunberg’s (who appears in the film) bout with depression is what spurred her to initiate a climate strike.

“[My sister] felt like hope got in her way,” Abbott says. “When she had hope, it took her out of the present moment because she was projecting into the future this life she would have. She identified hope as an obstacle, and it was only when she let go of that hope that this new spark of life bubbled through for her and she became present. Being present is ultimately what we all need to be right now.”