-

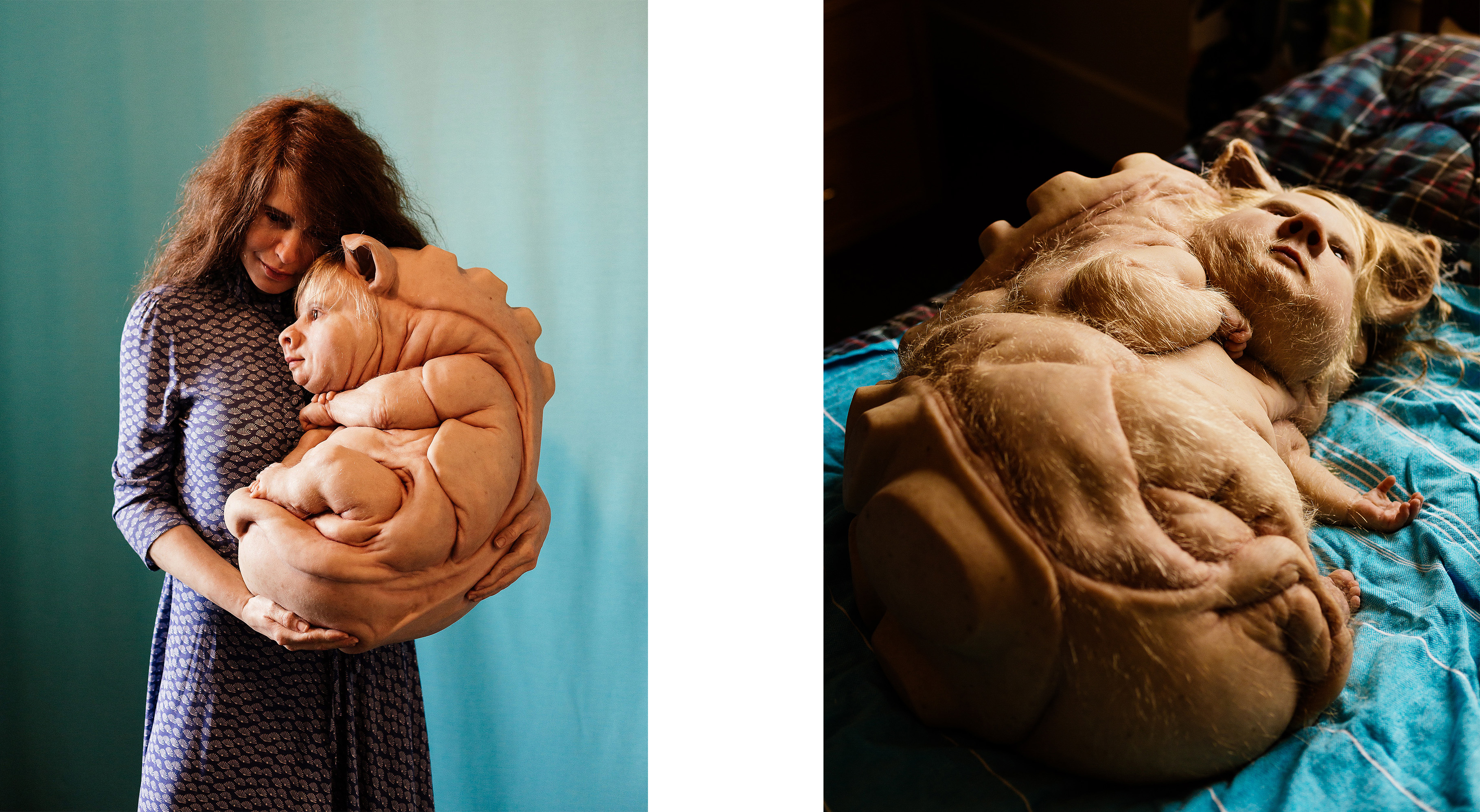

Patricia Piccinini sits beside Kindred, 2017.

-

Detail of Kindred, 2017.

-

The Young Family, 2002.

-

Prone, 2011.

-

The Couple, 2018.

-

The Comforter, 2010.

-

The Curious Case of Patricia Piccinini

Tender beings.

When Patricia Piccinini talks about her sculptures, her eyes soften, but her body tenses. Like most mothers, she wants to advocate for these children of hers, but she knows they are at the mercy of the world and they have a life of their own. Fresh off a 15-hour flight from her home in Melbourne—accompanied by her biological children, 13-year-old Hector and 11-year-old Roxy—the artist is a quiet island in the hectic atmosphere of the lobby at the Patricia Hotel located on Vancouver’s East Hastings Street. Having just taken a walk-through of her exhibition, Piccinini appears placid as she readies herself for the barrage of press and photos that will descend on her while she is in the city to introduce Curious Imaginings, on show as part of the Vancouver Biennale.

A few weeks prior, Peter Hennessey—Piccinini’s husband and creative partner, and a sculptor himself—arrived in the city with the artworks. “He showed me what was going on over FaceTime,” Piccinini says. Hers is a family practice: Hennessey participates in the creative process, from inception to installation. “Our relationship informs a lot of these works,” she says. “We go to bed talking about this stuff, and we wake up talking about it.”

Born in Sierra Leone, Piccinini, 52, grew up in Canberra, Australia, where her family moved following a brief stint in Italy after fleeing political unrest in the West African country in the late ’60s. Her artistic career began after she earned a degree in economic history from the University of Sydney and subsequently decided to enroll at the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne. It was during this transition that she met Hennessey, who then went on to pursue a bachelor’s of architecture at RMIT University, beginning his own artistic career alongside Piccinini.

Left: The Bond, 2016. Right: Teenage Metamorphosis, 2017.

A familial theme is present throughout the exhibition. Roxy appears in the show: she was the model for the little girl peering joyfully into the eyes of a sloth-like creature with very long fingernails in The Welcome Guest. Piccinini’s love for her work is palpable, even evidenced in the tender title of each piece. The Young Family is a work of meticulously layered and painted silicon and human hair that is painstakingly applied by hand, depicting a transgenic (containing genes from another organism) mother and her little ones: a little bit pig, a little bit human. One of the most notable works is Kindred, an orangutan-ish being holding her two offspring, one more human, the other more primate. All of these creatures have taken up lodging in 18 of the rooms at the Patricia Hotel, some having arrived from Piccinini’s latest exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Brisbane.

Curious Imaginings is one of the artist’s few shows outside the context of a gallery. Setting the show in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighbourhood was the brainwave of Marcello Dantas, the curator who brought Piccinini’s work to Rio de Janeiro in 2016. “If these sculptures came to life, there is little doubt that they would have a hard time fitting in,” says Dantas. “If these creatures were to come [to the city], where would they go? Where would they stay? [The Patricia has become] like a hotel of refugees of another dimension.” Indeed, news outlets and viewers routinely use words like “horrendous”, “disgusting”, and “disturbing” to describe Piccinini’s creatures. “I don’t want the work to shock. I want to make work that people can connect to,” she clarifies. Her art exists to challenge assumptions about what is acceptable and normal, versus what we have learned to perceive as unacceptable and abnormal. “We have a hierarchy in nature—we think that penguins are cute, but walruses are ugly. We’re all weird,” she says. “This work is actually about boundaries, and when you look at it, you see the collapse of boundaries between species, or between the organic and the artificial.”

“This work is actually about boundaries, and when you look at it, you see the collapse of boundaries between species, or between the organic and the artificial.”

Each sculpture is crafted at Piccinini’s studio in Melbourne by an eight-person team, which includes artists specializing in each step of construction. “If I was the sort of artist who made every bit of this work, I’d only have one work out there,” she explains. “Kindred took nine months to make as a team of people.” The team members have themselves become family to Piccinini and Hennessey, and it is this collective energy that imbues the body of work with a sense of deep care. “My strength is a kind of creative, imaginative, collaborative sensibility,” she says. This team structure also allows Piccinini to explore different mediums for expressing her ideas, which extend to video, drawing, and even the creation of the hot air balloon Skywhale in 2013, commissioned by the city of Canberra.

Walking through Curious Imaginings feels voyeuristic. The figures are so skillfully made, the skin wrinkling at the bend of a wrist, no vein missing. As a viewer, you wait for the sculpture to move. In each room, the scene is so intimate and dynamic that the impulse is to say, “Sorry! Didn’t realize you were in here” and close the door. In the nursery where Prone, the bat-nosed baby, is lying in a crib, you feel the urge to speak softly, to coo at the little one. Nature is filled with strange-looking babies, from giraffes that tumble out of their mothers with lanky legs akimbo to puppies that look like hairless rodents. Prone asks if human babies are any less strange than a newborn bat.

Left: The Welcome Guest, 2011. Right: The Coup, 2012.

“I have been watching people see her work, and something happens inside the viewer, which is a transformation from rejection to acceptance, rejection to empathy,” says Dantas. In the case of Piccinini’s artworks, their meaning is not in their technical accomplishment or ability to express something about cultural norms—though both of these things are vital aspects of the work—but in the relationship the viewer comes to have with the sculptures. Each creature asks the audience to consider it deeply, to move past initial shock and discomfort and really see the creation. Curious Imaginings requires patience, to spend a minute with your own reactions and assess them. “I think one of the things you might arrive at is the thought, ‘How can I continue to believe in these artificial categories when these boundaries have all collapsed?’ ” says the artist. Piccinini’s work is ultimately about vulnerability: the emotional process the sculptures evoke requires the viewer to admit they are uncertain, to let their guard down, and to enter the unknown.

Piccinini sits down next to Kindred and the sculpture takes on new life: both artist and artwork share the same tenderness. The orangutan’s brown eyes mirror her creator’s, and their hair falls the same way over their cheeks. Piccinini won’t touch her own sculptures for fear that it will give others permission to do the same; she knows her creatures’ boundaries. In front of the camera, in the small room full of strangers, Piccinini is herself a vulnerable member of the spectacle. Her rescue comes with a shuffling in the hallway. “Are my kids here?” Once again, her eyes soften as Roxy and Hector wander into the room, inattentive to the fanfare that surrounds their mom. Piccinini takes Roxy’s face in her hands, and if the moment were to freeze, there would be no way of telling whether the mother and daughter were just another part of the exhibit.

_______

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.