-

Gu Xiong in his Vancouver studio, in front of Crushed Coca Cola Can, 2014.

-

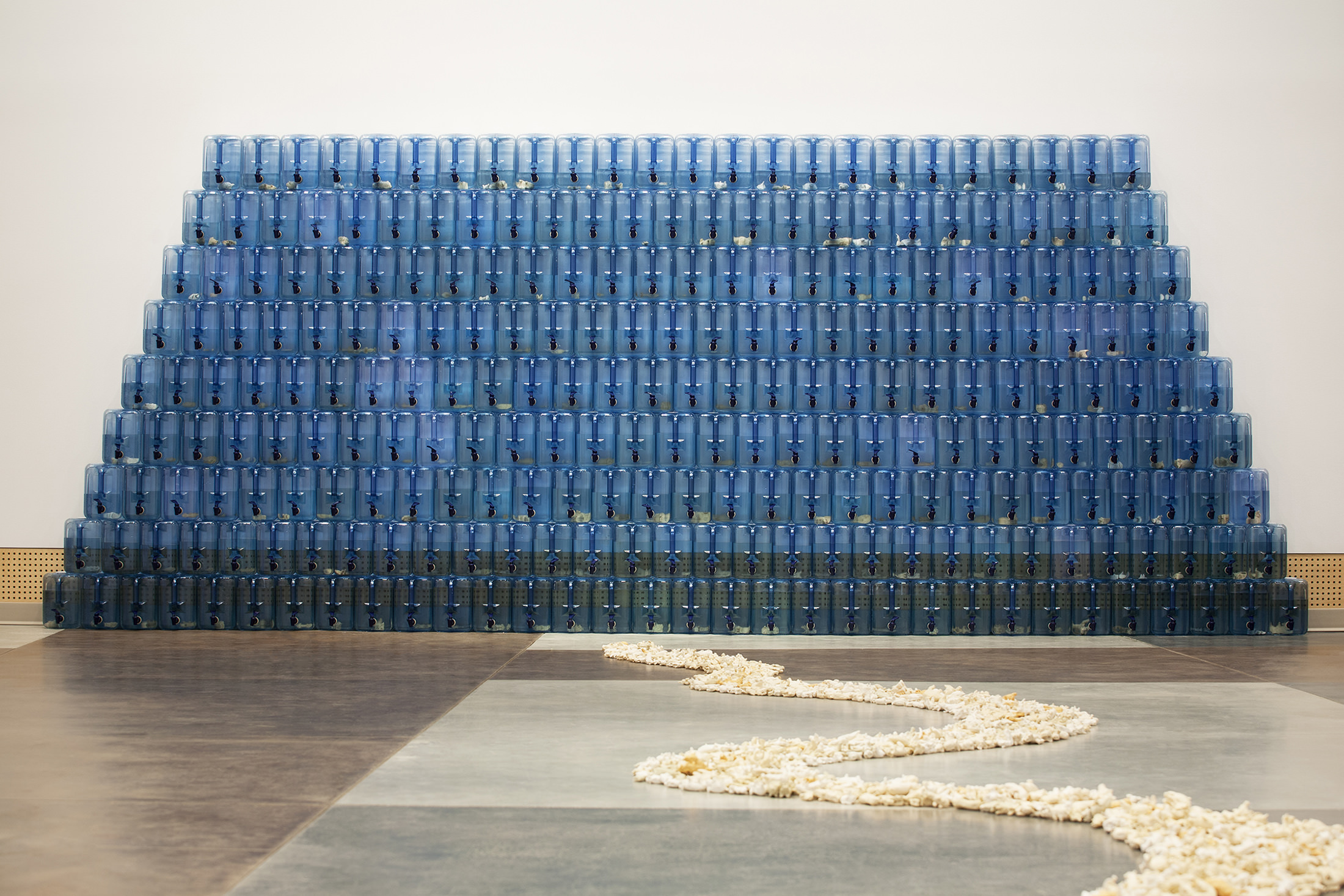

Pigs River, mixed media installation, 2013.

-

Enclosure, performance, 1989.

-

Sketches from the cultural revolution.

-

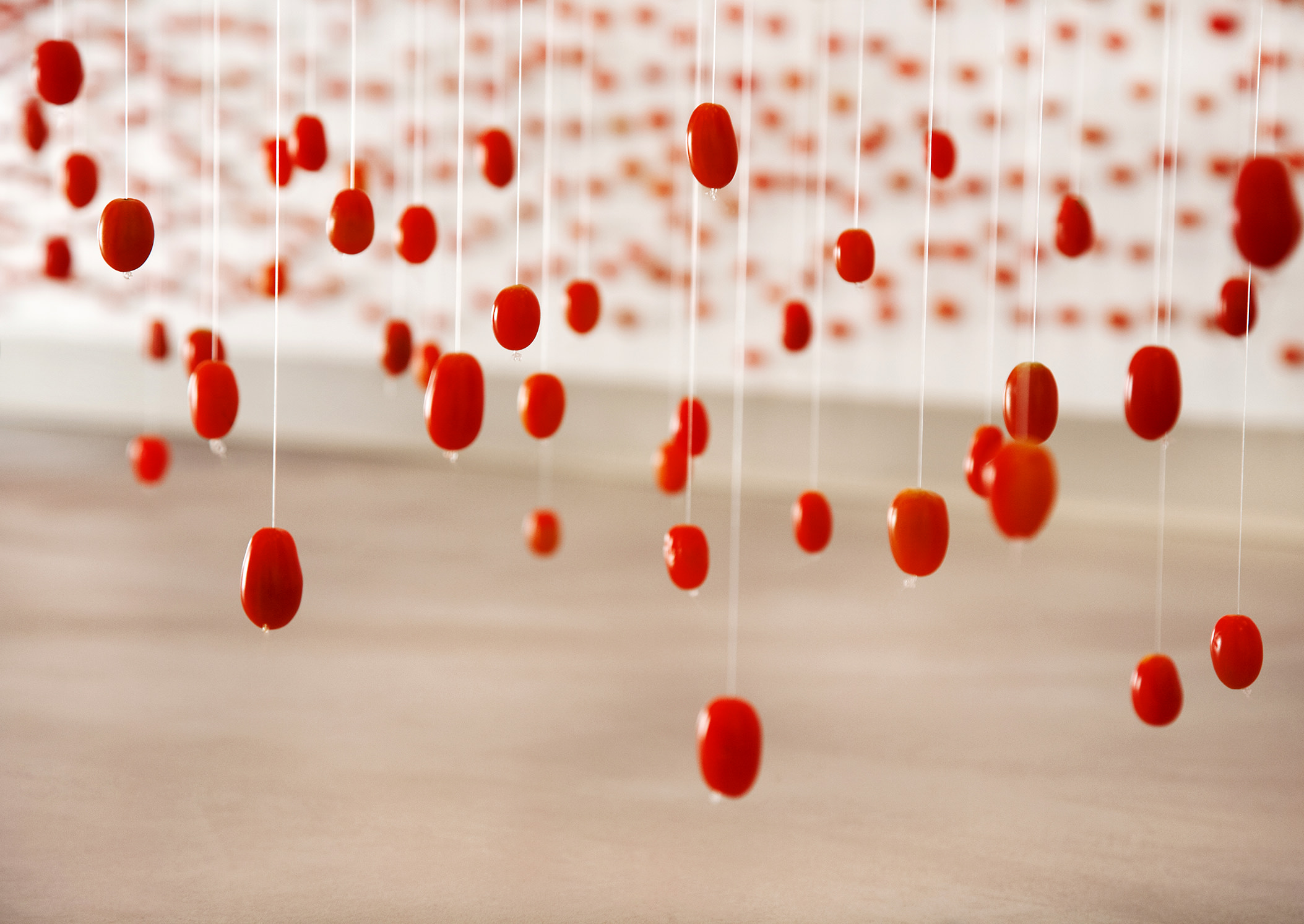

Here, There, Everywhere, mixed media installation, 1995.

Multimedia Artist Gu Xiong Connects the Personal with the Political

Art as a voice.

Vancouver artist Gu Xiong has never courted trouble. Yet trouble has dogged him: first as a young man growing up in China during the Cultural Revolution, then as an artist pushing the country’s artistic and political boundaries, and later as an immigrant to Canada, where he struggled to find his place as an artist in a new land. Gu’s work is provocative, but he is no Ai Weiwei, the activist artist who has achieved international fame by poking a stick at the Chinese government through his words and art. Gu strives to keep his relations with China on an even keel, partly for personal reasons—his parents, who are in their 90s, still live there. “I want to see them every year,” he says. But even if going back was not so important, Gu says he wouldn’t use his art to turn against the country he left behind. He wants his art to have global reach—he has exposure not only in North America, but also in some of China’s largest cities.

As Gu tells it, once he immigrated, his work evolved to reflect his expanded world view. The theme he has explored since leaving China is human migration. And while his earlier work focused on his personal journey, it now more often reflects the paths of others. A recent work titled A Bone House, which was part of a group exhibit at the Hubei Museum of Art in Wuhan, China, turns the spotlight on Canada. It tells the story of Chinese migration to Canada through haunting photographs depicting the bones of Chinese immigrants being cleaned, dried, and wrapped in white cloth in preparation for return to relatives in China. An accompanying video of the Chinese cemetery in Victoria that in 1937 replaced the “bone house” is still and silent, save for the ripple and roar of the ocean that carried the immigrant workers to Canadian shores.

Invisible in the Light, mixed media installation, 2014.

Gu’s subject matter also earned him a place in an exhibit last year at the Art Gallery of Ontario called Every. Now. Then: Reframing Nationhood. Featuring works by many Indigenous and immigrant artists, it pushed viewers to confront the dark, discriminatory parts of Canada’s history. Gu’s multimedia installation depicts the hardscrabble lives of present-day migrant labourers picking fruit in orchards around Niagara. Titled Illuminated Niagara Falls, the piece includes 4,000 photographs of people who toil for months away from home, as well as bottles of “illuminated” water from Niagara Falls and fruit baskets from farms in Ontario. It was presented alongside an installation by his daughter, filmmaker Yu Gu, whose three-channel video titled Interior Migrations shows the workers’ families in Jamaica and Canada. “This is globalization,” Gu Xiong says. “Those labourers move from country to country, from place to place.” Their labour is transported as readily as a tool.

Andrew Hunter, who co-curated the AGO exhibit along with Anique Jordan, Quill Christie-Peters, and Laura Robb, is a long-time friend of Gu’s and admires his art for its accessibility and intelligence. Gu’s work is informed by growing up during the Cultural Revolution, when art was used as a tool to convey a message, Hunter says. But he explains that Gu’s art does more than promote a narrow political perspective—it advocates for social change and social justice. And his pieces are deep, not simply the illustration of ideas, Hunter says. “They are profoundly powerful artworks because they bring together ideas with very creative and innovative ways of telling a story.”

Gu says the migrant workers in Niagara reminded him of the darkest period in his own life, when he was sent to the countryside to toil alongside peasant farmers during the Cultural Revolution. He had just finished high school and was exiled for four years, longer than many others because his father was on the outs with the Communist Party. When he turned 20, there was no end in sight for the gruelling 12- to 14-hour days spent in the fields. He despaired for his future. To stave off depression, he began spending his nights sketching scenes from farm life. He filled 25 notebooks in a search for meaning in his life. “That was a tough time. Art saved me.” He still has the sketchbooks; they were displayed as part of a group installation at the China Institute Gallery in New York and Seattle’s Asian Art Museum.

After the Cultural Revolution, Gu studied at Sichuan Fine Arts Institute and eventually became an instructor there. In the mid-1980s, China went through a period of openness and cultural exchange. Canadians were allowed entry, which is how, in 1985, representatives from the Banff Centre came to visit Gu’s printmaking studio at the institute. At the time, he was working on woodcuts based on traditional Chinese methods mixed with the influence of Western modern art methods; they depicted scenes of southwest China. The Canadians encouraged him to apply for a year-long exchange program. Gu knew nothing about Canada and wasn’t even sure the offer was genuine. “All I knew about Canada was that it is cold.” But he applied and was accepted, attending the school the very next year. His experience in the West radically transformed his art. He turned to large-scale installations that today often combine sculpture, photography, video, and prose.

To stave off depression, he began spending his nights sketching scenes from farm life. “That was a tough time. Art saved me.”

In 1989, Gu took part in the first China/Avant-Garde Exhibition at the National Art Museum of China. Government authorities were unenthusiastic about the show, but the artists themselves had chipped in to rent the gallery space, so it was allowed to proceed, Gu says. Throngs of people lined up for the show on opening day, he recalls, but after just three hours, it was shut down by police when one artist used a handgun to shoot at her installation inside the gallery. The closure foreshadowed the looming political crackdown, which culminated in the Tiananmen Square massacre months later.

Around the same time, the Banff Centre offered Gu another year as a visiting artist. By then he was married and had a five-year-old daughter; the decision to accept the post was absolutely wrenching. “I remember when the airplane was above the Yangtze, I was in tears.” Once he was in Canada, friends encouraged him to apply for permanent residency. Gu, who didn’t dare discuss the matter with his wife by phone or letter, initially resisted. But as the political situation in China worsened, he changed his mind. In September of 1990, a friend helped his wife get a visitor’s visa and she flew to Canada with their daughter, not knowing she would end up staying for good.

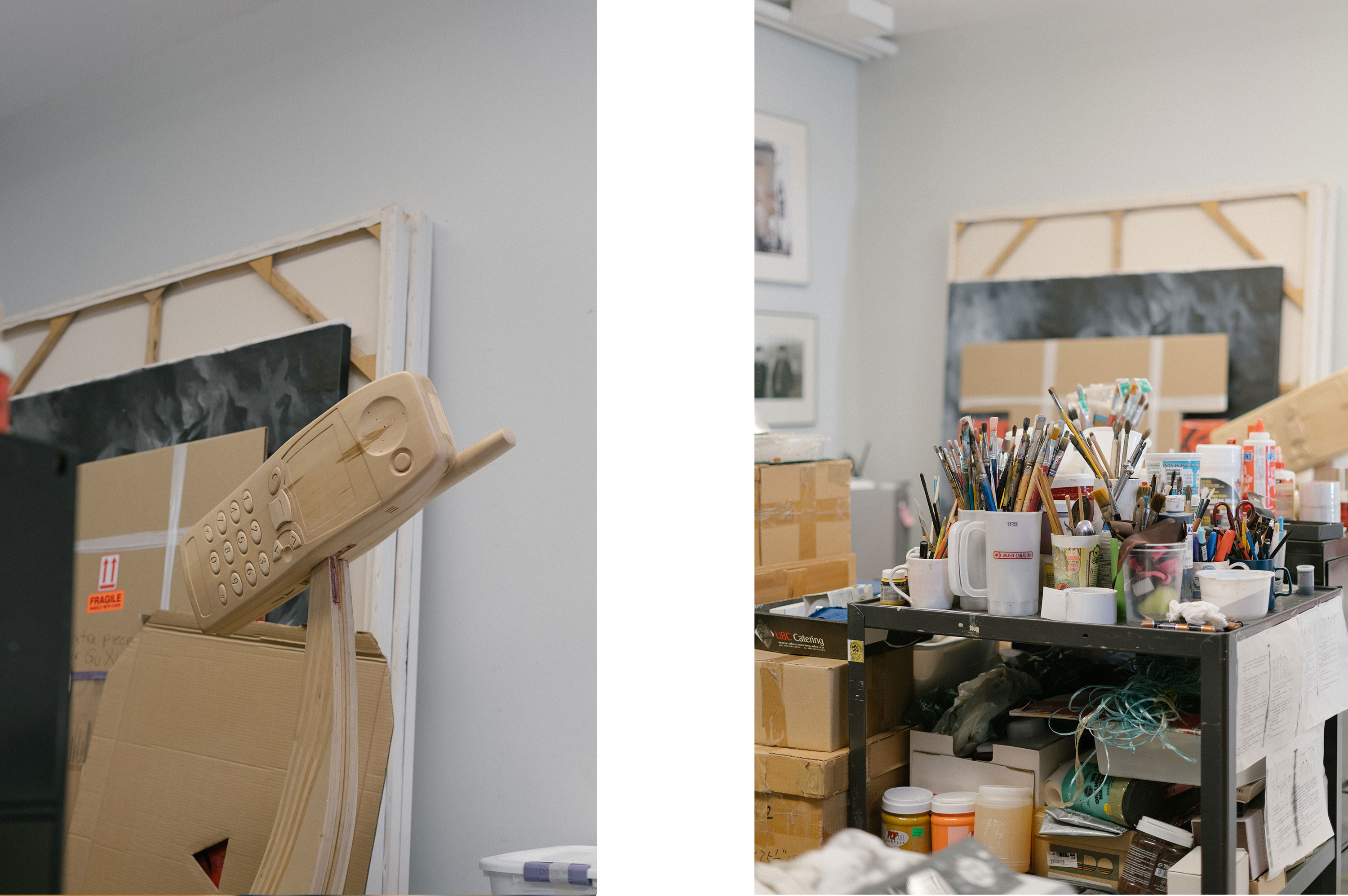

Gu Xiong’s Vancouver studio.

When Gu’s time at the Banff Centre was up, the reality of life as an immigrant artist with poor English hit home. He had moved to Vancouver and was working three minimum-wage jobs. He had little time for art, but he persevered in his off-hours. Unlike some immigrant artists, who resort to sketching tourist portraits in Stanley Park, Gu stayed true to his art, encouraged by friends who told him his talent would someday be recognized in Canada. He was working in a University of British Columbia (UBC) cafeteria busing tables when his big break came.

Once again, Gu had drawn artistic inspiration from his labour. This time, it was crushed Coke cans discarded by students that he tossed out with the garbage each day. He painted a series of large acrylics depicting the crushed cans. The paintings are reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans images. But unlike Warhol’s cans, which are intact and uniform like the ubiquitous product itself, each of Gu’s crushed cans is unique. To him, the cans symbolized the new culture he was trying to understand and his struggle to rebuild his life. “Every day when I threw away garbage bags, that became a symbol of how I recognized myself. Every day, I became a better person.” The series was displayed at Vancouver’s Diane Farris Gallery. “That exhibition gave very good publicity for me, and after that people paid attention to my work.”

Crushed Coca Cans, acrylic on canvas, 2014.

The show was a springboard for a couple of sessional teaching gigs at Emily Carr University of Art + Design and UBC, where he eventually gained a professorship. For Gu, art is not about perfecting expression through one medium. It’s about ideas. He begins with a concept and then chooses the most suitable medium for conveying his message. For that reason, says Hunter, Gu’s activist art is sometimes unfairly dismissed by people in the art world as “social work”. He has done amazingly well to rise from working in a university cafeteria to becoming a visual arts professor at UBC, Hunter says. “He’s an artist that deserves the big exhibition, the big retrospective project at the Vancouver Art Gallery or the National Gallery.” But often artists like Gu don’t get this because of barriers erected by a privileged, mostly white establishment that sets the art agenda, Hunter says.

Gu makes no apologies for his philosophy about art, and he teaches his students to start every project with thinking, “You have to say something, keep your own voice, be heard.”

_______

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.