-

Simon Beck’s supplies are a sketch and his Silva Expedition 54 compass.

-

The Icebreaker camp atop Jungfraujoch in the Swiss Alps. Photo by Claudia Cusano.

-

Simon Beck’s interpretation of a horned merino ram, a historic icon for Icebreaker.

-

Lac Marlou, Les Arcs, France: Simon Beck’s Cubert Koch Snowflake, which inspired a shirt in the Art of Nature collection.

-

In a six-hour time frame Simon Beck will walk, on average, 30,000 single paces.

-

Simon Beck’s Spirelli Tordue in Lac Marlou, Les Arcs, France.

-

Simon Beck, with a helper on the ropes, maps out one of the horns of his Icebreaker merino sheep head design in Jungfraujoch, Switzerland.

-

Simon Beck’s Sierpinski Triangle, as seen on select designs in Icebreaker’s Art of Nature collection.

-

Simon Beck examining the fresh snow in Jungfraujoch, Switzerland before beginning his design.

-

Simon Beck trekking to a fresh snow canvas in the mountains in Bachalp Lake, Switzerland.

A Design Collaboration: Simon Beck and Icebreaker

Naturally inspired.

Wool is an amazing, extraordinarily adaptable fibre, with many natural benefits and a wealth of history. Since sheep were first domesticated—and were hairy rather than woolly—mankind has been selectively breeding and experimenting to achieve a huge range of different effects for different uses.

Icebreaker is the New Zealand–based apparel company that takes natural, old-fashioned merino wool and spins it into high-tech whisper-like base layers.

Simon Beck is a snow artist. It’s possible you’ve never heard of him. Beck makes art—intricate and precise drawings—in virgin snow with nothing but an expedition compass and a pair of snowshoes.

Merino wool. Icebreaker. Simon Beck. A triad with a kinship to nature.

Icebreaker is a little company that put New Zealand’s merino wool on the map. Nothing about the budding enterprise was conventional. As a true New Zealand success story, the Icebreaker tale has been told many times. Jeremy Moon, founder of Icebreaker, was a 24-year-old Otago University graduate when, in 1994, farmer John Brackenridge tossed him a T-shirt made from merino wool, saying, “Try this.”

Moon had just been on a five-day kayaking trip, wearing polypropylene because “it was the cool stuff in the early nineties, and at the end of every day I’d be kind of sticky,” says Moon, recounting Icebreaker’s beginnings. “When I first tried [the merino wool shirt] on, it was like, man, if I can find a way for other people to have this same experience.” To Moon, the wool was the antithesis to his understanding of the fibre. “I grew up with wool being the enemy—heavy, prickly, and itchy.”

Brackenridge lived on an island with his wife, three children, and 8,000 sheep, and had no way of getting his message out. He needed to connect with someone. Moon was young, eager, and “had a dream of living in New Zealand and working around the world somehow.” He had an academic background in cultural anthropology and marketing, but no idea how a business based on merino wool could work. “I spent three months kind of trying to deconstruct what had happened, what the market was,” says Moon, “and I realized the great irony about the outdoor industry. The outdoor industry is about connecting people with nature, yet everything was synthetic. It was like, ‘get yourself in nature but wrap yourself in plastic.’ So, here’s something that’s technically superior, hasn’t been done, and is undiscovered, because merino wool was only used for $3,000 Italian suits.”

Moon grew Icebreaker from a $220,000 (New Zealand dollars) investment (a combined sum from eight individuals), by making every step part of his own journey, in which a vision unfolded and then took shape in the real world of business. Icebreaker has grown far beyond its original Wellington headquarters in its 20 years, and the global focus continues. Icebreaker now is available in 50 countries at 4,700 stores, producing $200-million U.S. in annual sales.

The history of the merino breed originates with kings and queens—in this case, in Spain. During the Middle Ages, it was considered treason to sell that country’s wool outside its borders. The official first reference to the merino breed dates back to 1307; today, half of the world’s sheep population is either a descendant or a merino crossbreed. No one is completely sure of the derivation of the term merino. The two most popular theories are that the original Spanish word derives from a Moroccan Berber dynasty that was called “Benimerines” in Castilian and fought throughout Spain during the Moorish era, or that it comes from the name of a government official in the Kingdom of León who inspected sheep pastures.

The merino genus in New Zealand has undergone intense breeding over the last 150 years to develop a uniquely long, strong white fibre. Merino wool—considered the finest and softest wool of any sheep—regulates the body’s temperature, keeps you both warm and cool, and draws moisture away from your skin (a process known as wicking). These qualities, along with its odour-resistant and anti-bacterial properties, make it ideal for high-performance athletic wear. And, it has the added advantage of being renewable—sheep need to be shorn at least once a year because their wool does not stop growing, making it nature’s gift that keeps on giving.

Icebreaker has pushed the limits of what can be done with merino, but the essence of the company is sustainability.

Moon didn’t exactly come from textile lineage. “My mom’s a potter and my dad’s a family doctor so I had to ask a lot of questions,” he says of Icebreaker’s try-and-try-again approach. “We found if we spun the yarns by making them tighter—how we press down the fabric to make it denser—it not only drapes better, but makes the fabric more compact.” Moon’s naiveté was critical to Icebreaker’s success because, he says, “Anyone that knew anything about textiles thought, ‘What? You’re going to use merino wool that normally goes into suits and you’re going to make underwear out of it? Have you lost your mind?’”

Icebreaker is a system of all-season garments that combines a natural fibre with the technology of engineered layers. The merino-wool base layers are measured for warmth by a numbering system—the bigger the number, the warmer the garment. “What’s different about merino,” says Moon, like a teacher educating his disciple, “is the natural fibres that absorb and release moisture to regulate temperature. [Merino] releases temperature to cool you down and absorbs moisture to generate heat. So there’s this incredible natural barometer.” With Icebreaker garments that are layered together, air is trapped in between each fine layer to generate even more warmth. (This summer, Icebreaker will launch Cool-Lite, a material that is 50 per cent merino and 50 per cent cellulose blended together to make it even lighter and cooler.)

“There are 187 families that supply us with 1,600 tons of merino every year from about three-million acres of Southern Alps in New Zealand,” says Moon. “We pay long-term contracts two to three years in advance at a price that they can lock in that’s profitable to them, which, in the last seven out of 10 years, has been considerably above the market price. And, in return, we get guaranteed ethics around environmental land care, and animal welfare, and quality.”

Icebreaker has pushed the limits of what can be done with merino, but the essence of the company is sustainability. One of Moon’s early mandates was for Icebreaker to be a global leader in sustainability and the cleanest clothing company in the world. “I don’t know of any clothing company that is cleaner,” he says of Icebreaker’s achievements to date—though he adds, “There’s always work to be done. Having a product made from natural fibres, well, that’s excellent. But everything can be improved.”

For some, that natural, sustainable image is at odds with Icebreaker’s manufacture in China. “If you want the worst stuff in the world—go to China. If you want the best stuff in the world—go to China,” says Moon of his decision to move to production facilities in Shanghai in 2003. He admits that transitioning to overseas manufacturing was a turning point, but says New Zealand was “constantly fixed at nine months behind, and the technology was 10 to 20 years behind the rest of the world.”

In 2008, Icebreaker launched the playfully named Baacode, a system that allows people to trace the merino wool in their garment back through the supply chain to the farms in New Zealand where it was grown. Baacode allows you to virtually meet the farmers, see the living conditions of the sheep, and follow the production process through to the finished garment. Traceability is increasingly used in the food industry, but it is very rarely available in apparel. Much of the environmental damage caused by the garment industry is the result of manufacturers buying cheap fabric from middlemen without taking any responsibility for how the fabric was made. “The global financial crisis triggered a real shift in consciousness—a rethinking of consumption,” says Moon. “So, globally, there are trends going back to quality, going back to craftsmanship, and simplifying life. And the role of nature has gone up.”

Moon, an avid adventurer, is continually looking for ways to connect with nature, and so, for fall/winter 2014, Icebreaker tapped snow artist Simon Beck to launch the brand’s first Art of Nature product series, an ongoing annual collaboration with artists who respect and work in nature, and who use objects found in nature in their work. Beck makes snow art in freshly fallen snow with nothing but an expedition compass and a pair of snowshoes. The Simon Beck collection for Icebreaker is made up of 20 garments with designs modelled after ephemeral art installations Beck has created by snowshoeing in the Alps. “I love people that are slightly offbeat and are doing something different and kind of redefining and using self-expression like artistry, but also exploring the relationship with nature,” says Moon of Beck.

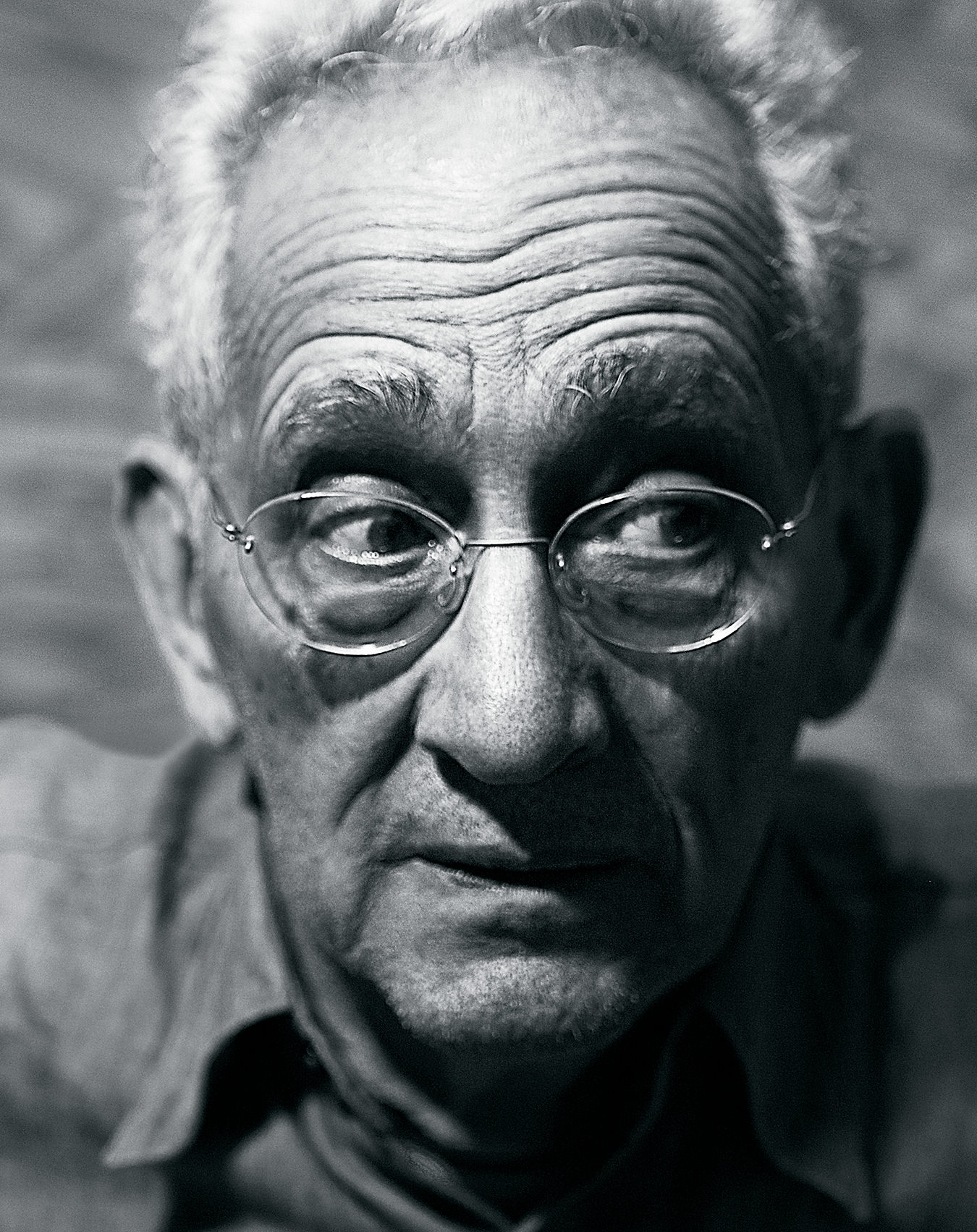

“I’m a loner,” admits Beck, his skin golden but weathered—undoubtedly from years of bracing the elements. He is en route to Jungfraujoch (elevation 3,454 metres, or 11,333 feet) in the Swiss Alps, where he will plod through the virgin snow to create a horned merino ram—a historic icon for Icebreaker.

Over the past decade, 55-year-old Beck has lumbered into freshly fallen snow to trample out his distinctly geometric patterns, footprint by footprint. Beck goes by a thumbnail sketch and gut instinct, rarely drawing out the entire piece beforehand because, as he dryly notes, “It’s too time-consuming.” Each snow drawing takes the artist between six hours and two days to complete, an impressive physical feat aided by years of training in the sport of orienteering. “I was growing too old for competitive orienteering, so plodding about on level snow was a low-grade activity,” says the artist.

“For years, I was the English madman who was going to get killed in Les Arcs,” says Simon Beck. Nowadays, he embraces his status as an outsider artist.

Beck walks for kilometres in the snow, all alone, to create his drawings. He spends hours creating each design just to have it covered by snowfall or have the mountain winds blow it away across the valleys. “Gradually, the reason [for doing this] has become about photographing my drawings. I choose sites where I have a good vantage point to take photos. What counts is the photographs—this is the key, as without that I have no work.”

Watching Beck work is a lesson in precision. He has a lean, taut frame and walks carefully but swiftly, with sketch and compass in hand, stopping only to survey his bearings with his Silva Expedition 54. There is no hesitation in his step, and he often picks up speed to a jog. At this pace, Beck cannot be weighed down and so is outfitted in layers of Icebreaker. He sometimes walks lines multiple times to get them deep enough that the angle of the light creates dimension.

Although his works on ski slopes may attract a captive audience, his regular haunts in the French Alps, where he lives, tend to be less accessible. “For years, I was the English madman who was going to get killed in Les Arcs,” says the mountain man. Nowadays, Beck embraces his status as an outsider artist, boasting about his Nikon D800.

To Moon, modern life is in direct contrast with Beck’s solitary existence. “We live in cities because we get a payoff from the intensity, the social networks,” says Moon. “But it comes at a cost of spiritual and emotional burnout unless we find ways to reconnect with our body, reconnect with the people that we love, reconnect with where we’ve come from—which is nature.”

Icebreaker has, from the beginning, had a connection between people and nature. During the early days, Moon stayed on a sheep station for an extended period. “I saw this amazing connection between the families, the animals, and the environment to create this fibre from an alpine region from the most pure parts of New Zealand,” he says. “And what really inspired me was the idea of connecting people with nature in nature.” For a country known for adventure, natural beauty, and sheep, it’s ironic that the outdoor clothing market was, 20 years ago, dominated by synthetics.

Moon does feel pressure to launch more collections, more SKUs—the more, and even more, that the apparel industry craves. “We keep on seeing new opportunities where we could apply merino and I could make a lot of beautiful products. My friends say, ‘Why don’t you do a golf collection?’ Every time I make a choice, it actually impacts our identity, and I’ve probably been a lot more thoughtful around how we create products.”

Moon has made many big decisions over the years, and for the first time in the company’s history, someone else will be calling the shots. Moon appointed a new CEO, Rob Fyfe, four months ago. The two sit across a table from each other at Icebreaker’s current headquarters in Auckland. “It’s a real yin and yang type case,” he says of the fresh hierarchy. “I’m working the same, but I’m working differently—sticking a bit to my roots.”

Icebreaker was the pioneer for merino wear in the active outdoor market. Competitors have come into the space and crowded it but, as with art, the original is an original. Warhol is Warhol. Beck is Beck. Icebreaker is Icebreaker.