The Legacy of La Maison Guerlain

Scents and sensuality.

“This was my office, and my father’s,” says Jean-Paul Guerlain, sitting in the serene honey-coloured salon of number 68 Champs Élysées, the stylish building that has been home to the celebrated perfume company since 1914. He and his family lived on the fourth floor for several years, he says, and he remembers watching the liberation of Paris from the balcony as a boy. Today, traffic roars, tourists crowd the wide sidewalks of this grandest of thoroughfares, and the boutiques that line it are those common to cities everywhere. And yet, mute out evidence of the 21st century and much is unchanged: the balconied façades, the leafy trees and especially the calm elegance of the House of Guerlain.

White-haired and patrician, Jean-Paul Guerlain is the fourth generation of France’s first family of parfumeurs. The creator of Vetiver, Habit Rouge, Chant d’Arômes and numerous other fragrances, he can track his lineage—and the company’s tradition of making women feel beautiful—back to 1828. “The first Guerlain was a chemist,” explains Sylvaine Delacourte, the company’s fragrance creative director. Trained in England, Pierre-François-Pascal Guerlain created cucumber- and strawberry-based skin cremes, salves and breath-freshening products, all revolutionary for their time. Formulating a citrusy Eau de Cologne Impériale for the Empress Eugénie as a migraine remedy earned him the title of official perfumer. Soon a royal favourite, he designed scents for Queen Victoria, Queen Isabella of Spain and the court of St. Petersburg.

A defining moment occurred with the second generation of the Guerlain family when Aimé, the eldest son, developed a fragrance called Jicky, its name celebrating a woman he had met in his youth. He had never married, and at age 60 created this “poem” to his lost love. (A romantic family, these Guerlains; to them, fragrance is always a personal expression.) Prior to the introduction of Jicky, scents had been mostly single-note florals, whereas this was a symphony not only in its complexity but also in its ingredients, a daring accord of synthetic substances and pure floral essences that made it the first genuinely modern perfume. This ground breaker first scented the air in 1889, the same year the Eiffel Tower was unveiled at the Paris World’s Fair. With its alliance of bergamot, rose and jasmine, plus tonka bean and vanilla—and coumarin and vanillin, their synthetic cousins—it seemed to symbolize the new technological expertise. Moreover, Jicky didn’t just imitate nature, it stirred emotion so much that women initially considered it too radical and handed it to their menfolk.

Guerlain perfumes have always been in gentle step with the zeitgeist. The early part of the 20th century was a thrillingly turbulent time to be living in Paris, an extraordinary era that the House of Guerlain, now with a new generation in charge, mirrored in a cavalcade of now-classic perfumes. The soft-focus art of the Impressionists inspired Jacques Guerlain’s romantic L’Heure Bleue in 1912. As Europe swung into the Roaring Twenties, the passion for all things oriental met its match in Mitsouko, the first chypre (which Luca Turin has called “the best perfume of all time”). Later Vol de Nuit flew in, dedicated to women of action; Sous le Vent was created for Josephine Baker; and, during these years, the most famous Guerlain perfume ever was born.

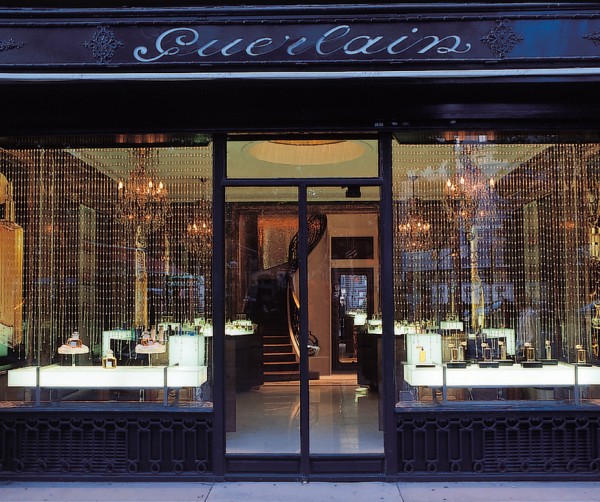

La Maison Guerlain, 68 Champs Élysées, Paris.

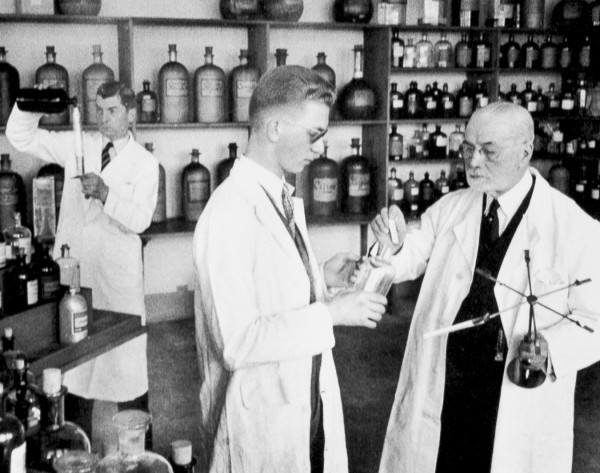

“A lot of things happen by chance. It’s good when there’s not so much premeditation,” says Thierry Wasser, who joined the company in June 2008 as a perfumer, the first non-Guerlain “nose” in the company’s history. Jacques Guerlain was very curious about new technology, Wasser explains: “He took Jicky and put a whole lot of vanillin in, and said ‘Wow!’” Then Guerlain reshaped and rebalanced it, and launched the voluptuous result in 1925 as Shalimar, which means “temple of love” in Sanskrit. Its distinctive bottle with the blue fan-shaped stopper represented the company at the genesis of art deco, the Decorative Arts Exhibition being held in Paris in 1925.

Luca Turin once wrote, “Guerlain never starts with a blank sheet of paper but with a blurred filigree of everything they ever built.” Devotees allude to the “Guerlinade”, the foundation notes of jasmine, rose, vanilla and tonka bean, a recognizable signature that is the basis of most of the company’s fragrances. These are authentic ingredients. The jasmine, for instance, comes from Egypt, India and the southern French town of Grasse, renowned as a centre for fragrance. The famous May rose, also from Grasse, is blended with lavishly scented damask rose. Guerlain is the leading user of lemon-scented bergamot in the perfume world, and is one of the few perfumers to purchase natural iris, the most expensive raw material in the world.

Over its 180-year history, the company has put its name to 760 perfumes, the recipes hand-written in a family formula book stored in a vault. Time has occasionally necessitated changes. Shalimar was reorchestrated. Parure was discontinued due to the legislation of one of its ingredients, oak moss. “We couldn’t find a substitute,” says Wasser, so rather than compromise, the company simply rang down the curtain (although the name survives in its makeup line).

Today, Guerlain has boutiques in cities worldwide, including Toronto and Montreal, and spas in many countries, but its flagship remains its long-time location on the Champs Élysées. In 2005, Guerlain redesigned the boutique, a listed monument, with architect Maxime d’Angeac and interior designer Andrée Putman working magic on the space with gold and transparency to create “a journey to the centre of the fragrance”. Gleaming mosaic walls curve and undulate, glass bead curtains filter out the exterior world and, between entresol and ground floor, a gold-chain chandelier hangs like a single, colossal drop of perfume. In this garden of sensuality, a lineup of black paper fans stands ready to be sprayed with perfume and wafted through the air. On the first floor is the beauty spa, still with the lamps by Giacometti and furniture by Jean-Michel Franck that were commissioned for the world’s first beauty institute when it opened in 1939.

When I was 16, my grandfather said, ‘Remember to create the perfumes for the women you are in love with and the women you live with,’” says Jean-Paul Guerlain. “That’s what I did my whole life.”

From its earliest days, the Guerlain name has been as synonymous with skin care and cosmetics as with perfume. When alabaster skin was the identifying mark of a lady, Guerlain originated skin whiteners and powder such as pale pollen. Come the trend toward a natural tan, and the company was first out of the gate in 1984 with Terracotta, makeup that provided a warm glow.

“It’s always exciting to make something new when you have a magic name like Guerlain,” says Olivier Échaudemaison, creative director of makeup since 2000. He describes the uncomplicated black case for the eyeshadow palette as “modern chic”, saying of the subtly embossed Guerlain name: “We are not very ‘logo’. We are not very ‘show-off’.” But they are very practical, as in the Le 2 de Guerlain, a “double” mascara with different formulations for upper and lower lashes. “I want to bring back the innocence of big eyes” from the 1960s, he says. As with Guerlain perfumes, the goal is never to shock, but to seduce.

In 1994, Jean-Paul Guerlain passed the reins to luxury-brands leader LVMH, but the corporate culture remains familial. Sylvaine Delacourte, who has been with the company for 20 years, emphasizes her pride: “It’s the top of the market. After the caviar, what can you eat?”

The loftiest peak of this perfume luxury is the bespoke fragrance. It starts with a two-hour consultation held in the same salon that was once Jean-Paul Guerlain’s office, where Sylvaine Delacourte interviews a client intensively, “travelling through their memory to find positive smells”, she says, taking them back to their childhood on an individual olfactory heritage walk. Having established a client’s favourite scents from the past (which can range from a few to as many as 30), she further refines preferences with a series of visual cards “to validate what the client says, to confirm and to enrich”. Next stage: picking fabrics from a varied selection of colours and textures. Finally, from a large tray of small bottles, Delacourte chooses blends and pure essences, for the client to say, “Yes, you’re on the right track.” The exact brief is then translated into two litres of custom-made fragrance.

Archival photo of Jacques Guerlain (right) in his laboratory.

Thierry Wasser works closely with Sylvaine Delacourte and Jean-Paul Guerlain. “I try to teach him what I know, to give him what I have learned in 55 years,” says Guerlain. A bon vivant, a gourmet, a lover of gardens, horses and, above all, women, this is a man whose knowledge of scent is encyclopedic. He created Vetiver while still in his teens; launched in early 2008, Vetiver Pour Elle is the house’s current best-seller, an astonishing feat given that it is a rewrite of a 50-year-old fragrance. Ask him why it’s still successful and he tells you, “It was created with love.” Ask him to name his favourite fragrance, and he smiles and says, “The one the lady I am in love with wears.” It’s been his guiding rule. “When I was 16, my grandfather said, ‘Remember to create the perfumes for the women you are in love with and the women you live with,’” says Guerlain. “That’s what I did my whole life. I hate marketing people because they don’t create perfume with love.” Modern market demands also force strict deadlines that require a perfume to be ready six months or more before it goes out into the world. Jean-Paul Guerlain worked on Chant d’Arômes, the demure bouquet of spring flowers he conceived in 1962, until two days before its launch. And what of perfumes “created by” celebrities? “That’s stupidity,” he says. “If there’s no romance in perfume, there’s no perfume.”

There’s laughter and swift French conversation as Wasser recalls a television interview in which Jean-Paul Guerlain described the effect of vanilla in a woman’s perfume on the male psyche. Brief translation: it’s a magnet, and men are doomed.

From the start, men have also had their own Guerlain fragrances. The reason that women wear them too, says Guerlain, is that “women and men have the same taste in food … lobster, vanilla ice cream.” He points out that in the mid-sixties, when he created Habit Rouge, “at that time men’s fragrance was very spicy, very bitter. My new fragrance was sweeter. I used two or three new materials never used before and never used since.”

This tradition of using unexpected scents continues in the recently issued Guerlain Homme. “As a little wink to Monsieur Jean-Paul [Guerlain], we used a tiny drop of vetiver oil,” Wasser says, adding, “We wanted something very fresh. Monsieur Guerlain said, ‘Why don’t you try rhubarb?’” Rhubarb? Well, they explain, the greenness and tartness go very well with citrus and mint, the other elements. And should you remark that rhubarb is an unusual ingredient, in fact, you can’t recall ever hearing of it being used before, but that in this context it seems absolutely right, Wasser simply reminds you that, after all, “Monsieur Guerlain is the king of firsts.”