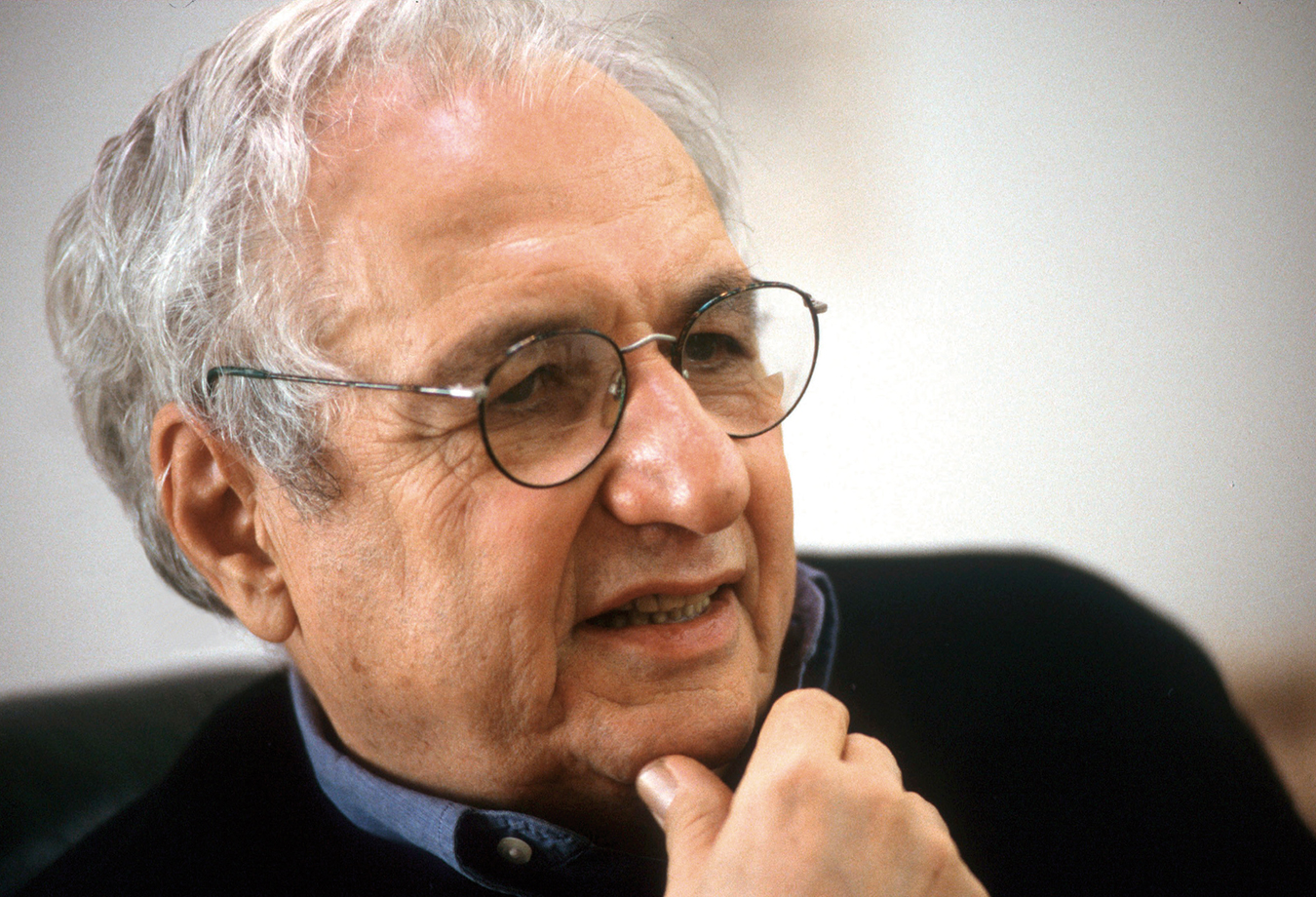

Frank Gehry

Redesigning spaces.

He may be the most celebrated and sought-after architect of our time, but Frank Gehry insists that all he wants is to be a good neighbour.

“I’m an egomaniac like all the others,” he confesses happily. “But I’m a Canadian egomaniac. Modesty is built into our lives.”

That modesty, Gehry argues, is also built into his architecture. “My buildings are inclusive,” he says. “You respect what’s next door, even when it doesn’t look like what you want it to. If you just see pictures of the Bilbao Guggenheim, you think it’s Martian or something, but I spent a lot of time fitting it into the city.”

Anyone who has seen Gehry’s 1997 masterpiece knows it is an icon, but it’s one that works as part of its context, not simply as something within a context. It connects with the city in many ways, both physically and symbolically. Up above, an elevated tramway track almost runs through the gallery. Down below, riverside terraces join the city to the Nervión, and provide breathtakingly beautiful spaces to watch as it flows to the North Atlantic.

This vista is just one among many the 79-year-old architect has created during his long and distinguished career. Born in Toronto during the Depression, Gehry’s extended family was large and relatively prosperous. A cousin now serves as a cabinet minister in the Ontario government, and Gehry makes regular trips to see the city and his relatives. Since 1947, however, when the Gehry family packed up and moved to Santa Monica, California, that city has been Gehry’s home. “I don’t think I could’ve had the same career if I’d have stayed in Canada,” he says. “I don’t think it would have been possible.”

Not so in the land of opportunity south of the 49th parallel. Yet even so, Gehry didn’t come to public attention, by his own account, until he was in his 60s. If nothing else, his experience proves the adage about architecture being an old man’s game.

Still, he has made good use of his years in the sun: Gehry’s work virtually defines the era. Wooed by governments, corporations and cultural organizations, he can change a city with a single project. Few architects can make such a claim. Visitors come from around the world to ogle his designs. The phenomenon even has its own name: the Bilbao Effect, after the Guggenheim.

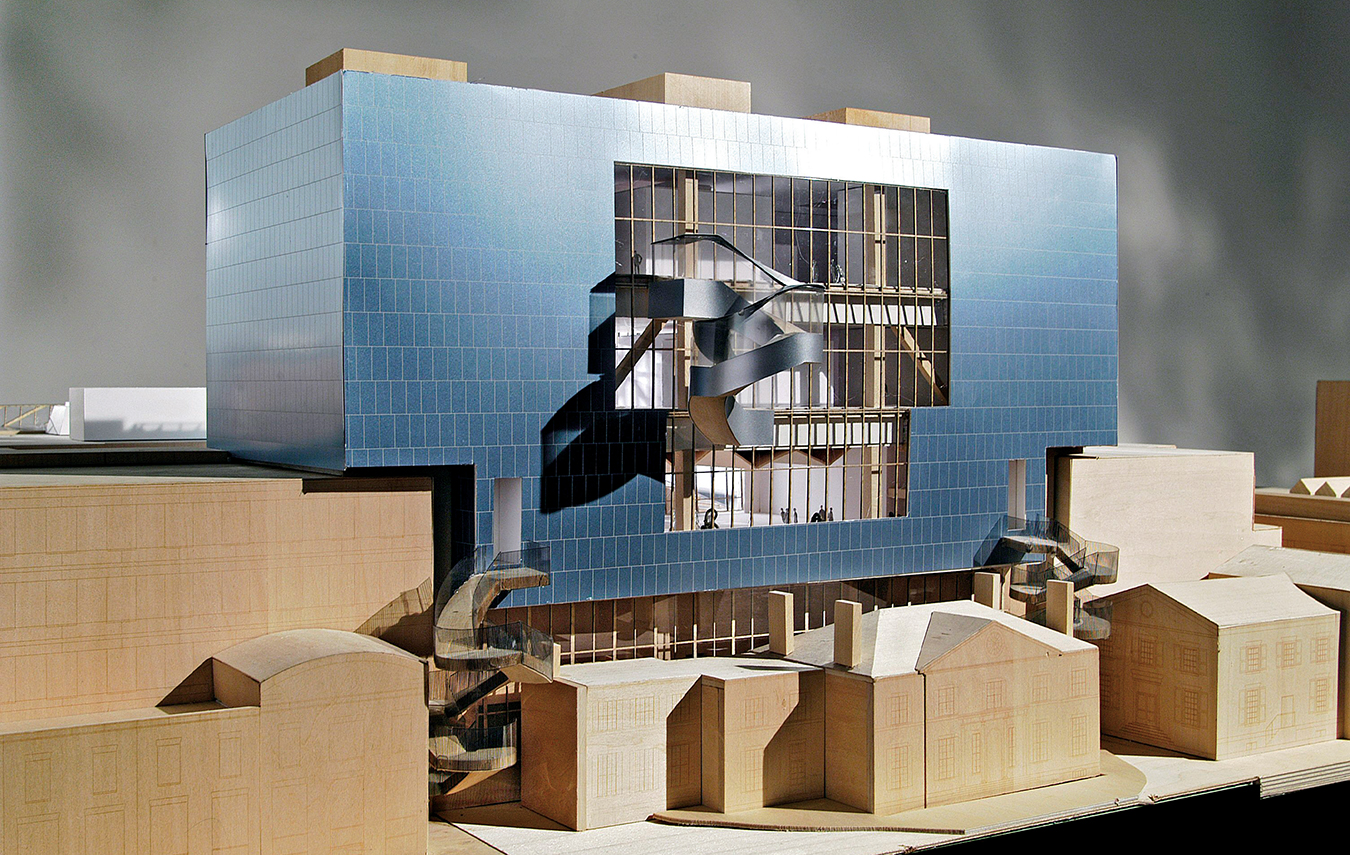

Yet his first major Canadian commission, the $222-million transformation of the Art Gallery of Ontario in Toronto, is unlikely to take its place among these global landmarks. True to its Canadian roots, it’s simply too modest to attract the usual Gehry-related levels of attention. This isn’t to say the project won’t rank among his finest. If anything, the restrictions—mainly of space, but also of money—seem to have prompted Gehry to produce a work of unusual, though wholly admirable, restraint.

Not that the new AGO, which opened November 14, doesn’t have its share of Gehry flourishes. He has introduced a series of striking stairwells inside the gallery and out, the most dramatic of which extends 10 metres from the addition on the back of the original building. Functionally, it provides access between the contemporary art galleries on the fourth and fifth floors. It also doubles as a viewing platform from which visitors can take in a grand urban vista that even includes a glimpse of Lake Ontario.

Gehry’s buildings engage and entertain us as they celebrate the messy vitality of our existence.

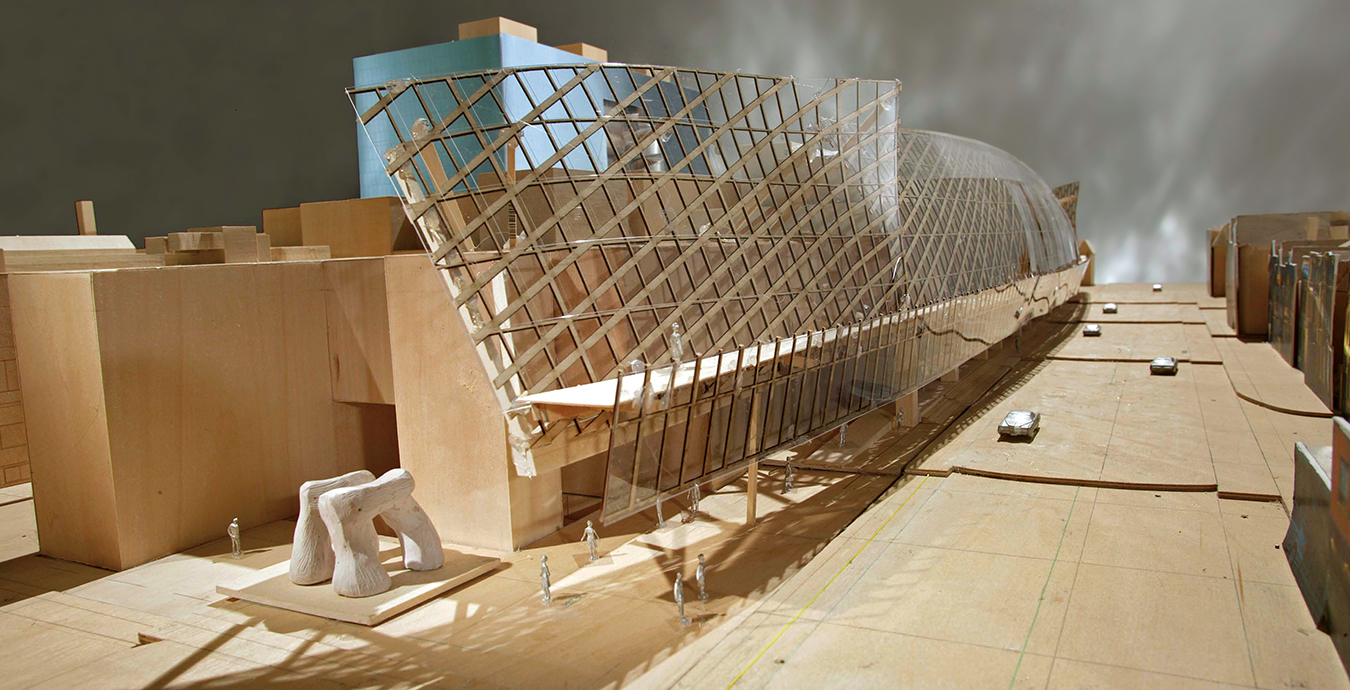

On the front of the building, the big gesture is a long glass-and-wood gallery called Galleria Italia that extends the length of the main façade on Dundas Street. It is a place to view sculpture, as well as to enjoy hitherto unseen views of the downtown core. It is moves like this that demonstrate the truth of Gehry’s stated desire to engage with his surroundings. His revamped AGO is as aware of the city around as of the art within.

Speaking of art, this is one cultural institution that hasn’t lost sight of its purpose—to display artworks. With their devotion to design, architects have often been given free rein to ignore such mundane matters as function. For example, at the Royal Ontario Museum’s controversial new addition, the Michael Lee-Chin Crystal, architect Daniel Libeskind has eliminated just about every right angle and straight wall. The price of his multi-faceted conceit is large volumes of empty space that are all but unusable. This is the kind of thing that drives curators crazy, and makes for rooms that can seem unfinished in places. For Libeskind, however, it seems nothing can be allowed to interfere with the architecture.

By contrast, Gehry has bent over backward to put the AGO’s collection—as well as that of the late art collector and gallery benefactor Ken Thomson—in the best light. This is true both literally and figuratively: an elaborate system of reflective light wells brings sunshine from the roof down into the innards of the AGO.

More important is the physical layout of the gallery; for even the most casual visitor, a trip to the AGO is an odyssey of sorts. No more dead ends and corridors that go nowhere. Now we travel through the different periods of Canadian art, each following naturally from the one before. Major figures—from Cornelius Krieghoff to Michael Snow—have rooms of their own. The idea is to allow visitors a chance to experience a critical mass of an artist’s work, as well as providing them with an understanding of the trajectory that has taken the visual arts from landscape to abstraction, from realism to conceptualism.

Though we shouldn’t put too much in stock comparisons between the ROM and the AGO, it’s interesting to see how each, in its own way, represents different—even contradictory—strains of contemporary architecture. Where Libeskind is all about confrontation and provocation, Gehry devotes himself to the pleasure of architecture. Where the Crystal is all sharp angles and looming façades, the AGO is soft, transparent and inviting. The glazed exterior of the Galleria Italia, for instance, allows passersby to penetrate the building long before they actually enter it. Given the often-threatening nature of art, especially contemporary art, this can be counted on to enhance a reluctant public’s willingness to visit the gallery.

“I like people,” Gehry says. “And I hope it shows. The idea here was to engage the city. When you go to the AGO, you’re always looking back at the city.”

Gehry’s building offers views of the city that have never been seen before. In this sense, it is as much about its civic surroundings as its cultural contents. For example, Gehry went out of his way to ensure that the gallery has a relationship with its spectacular neighbour to the south, the Ontario College of Art & Design. Created by bad-boy British architect Will Alsop, the OCAD building, nicknamed the Flying Tabletop, is suspended in the air on brightly coloured steel legs. Since opening in 2004, Alsop’s spectacular creation has become an icon of the new Toronto. It is the kind of building that people either love or hate. In the beginning it was mostly the latter, but in the years since, the Tabletop has established itself as one of the city’s most popular structures.

“I raised my building up to meet Alsop’s,” Gehry explains. “I hope he likes it.”

He undoubtedly will. Despite their differences, the two buildings speak to one another in a way that will bring new life to the busy downtown precinct.

The Art Gallery of Ontario hasn’t lost sight of its purpose—to display artworks—and Gehry has put the gallery’s collection in the best light.

Of course, from the moment the AGO announced that Gehry would redesign the gallery, many have wondered why he wasn’t asked to do a new structure. Remaking an existing building just isn’t the same thing. Given the fact that Toronto is embarking on a huge, multi-billion-dollar revitalization of its long-neglected waterfront, some have argued that Gehry should have been given a site on the shore of Lake Ontario and, say, $1-billion to produce his most brilliant building ever.

“I’d love to do something free-standing,” Gehry says. “But it wasn’t to be. It’s hard to remodel a building, especially a Barton Myers building. It would have been great to do something that wasn’t encumbered. The situation at the AGO was less than ideal.”

Regardless, most will soon forget what the old gallery looked like and grow to love the new one. Besides, since the AGO first opened in 1901, it has undergone a number of changes and additions. The original neo-classical building was expanded in the 1970s by John C. Parkin and again in the early 1990s by Myers. Although architects like nothing so much as an empty site, a tabula rasa, typically cultural institutions such as the AGO grow over the course of decades.

In the case of the AGO, however, Gehry’s remake could well be the last; residents of this well-organized downtown neighbourhood have let it be known that they would oppose any further developments. And if the truth be told, they were less than enthusiastic about this one. That, too, will change.

“I’m excited about it now,” Gehry says. “But I spent a lot of time worrying. The thing we wanted was a definite budget, but we kept on going back and forth and getting double messages. We went through enough iterations that we finally came up with something reasonable. It got better.”

Despite its innate conservatism, Toronto is waking up to the fact that of all the buildings that constitute the city’s so-called cultural renaissance, the new AGO will be the easiest to love. In Gehry’s hands, the architectural avant-garde has morphed into a kind of design populism we haven’t seen before. No other architect has received such critical respect and mainstream acclaim. People don’t just admire his buildings; they actually like them. After decades of modernist hegemony, when theory had it that form must follow function, Gehry’s brand of architecture can only be understood as a kind of liberation.

Unlike his predecessors, who thought they could control (and improve) human behaviour through architecture, Gehry’s buildings try instead to engage and entertain us as they celebrate the messy vitality of our existence. He rejects the idea that human activity can be confined to a series of boxes, big or small. He revels in complexity and contradiction, while also embracing connectivity and community.

Ultimately, Gehry’s AGO may best be viewed as a metaphor for the city itself: diverse, varied and by turns unexpected, but in the final analysis deeply rational, if not always obviously so. This is a building that kids will enjoy as much as their parents. Those looking for fun will find it here. Others searching for something more profound will also be satisfied.

For Toronto, a city known for its timidity and self-doubt, the Gehry AGO marks something of a breakthrough. For all the limitations of space and money, this is one building that couldn’t have been built anywhere else.

Photos ©2008 Art Gallery of Ontario.