-

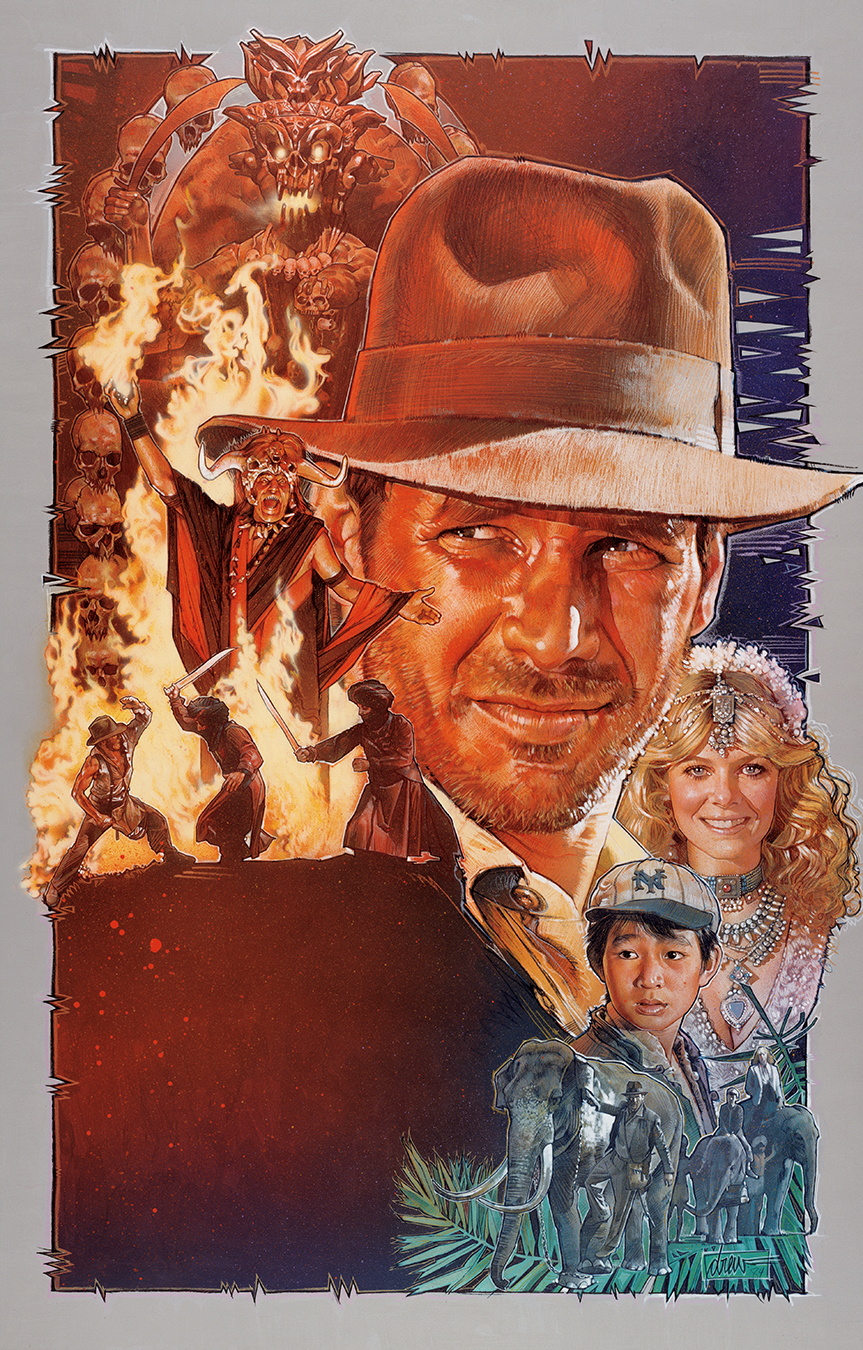

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. ©Lucasfilm Ltd. 1984.

-

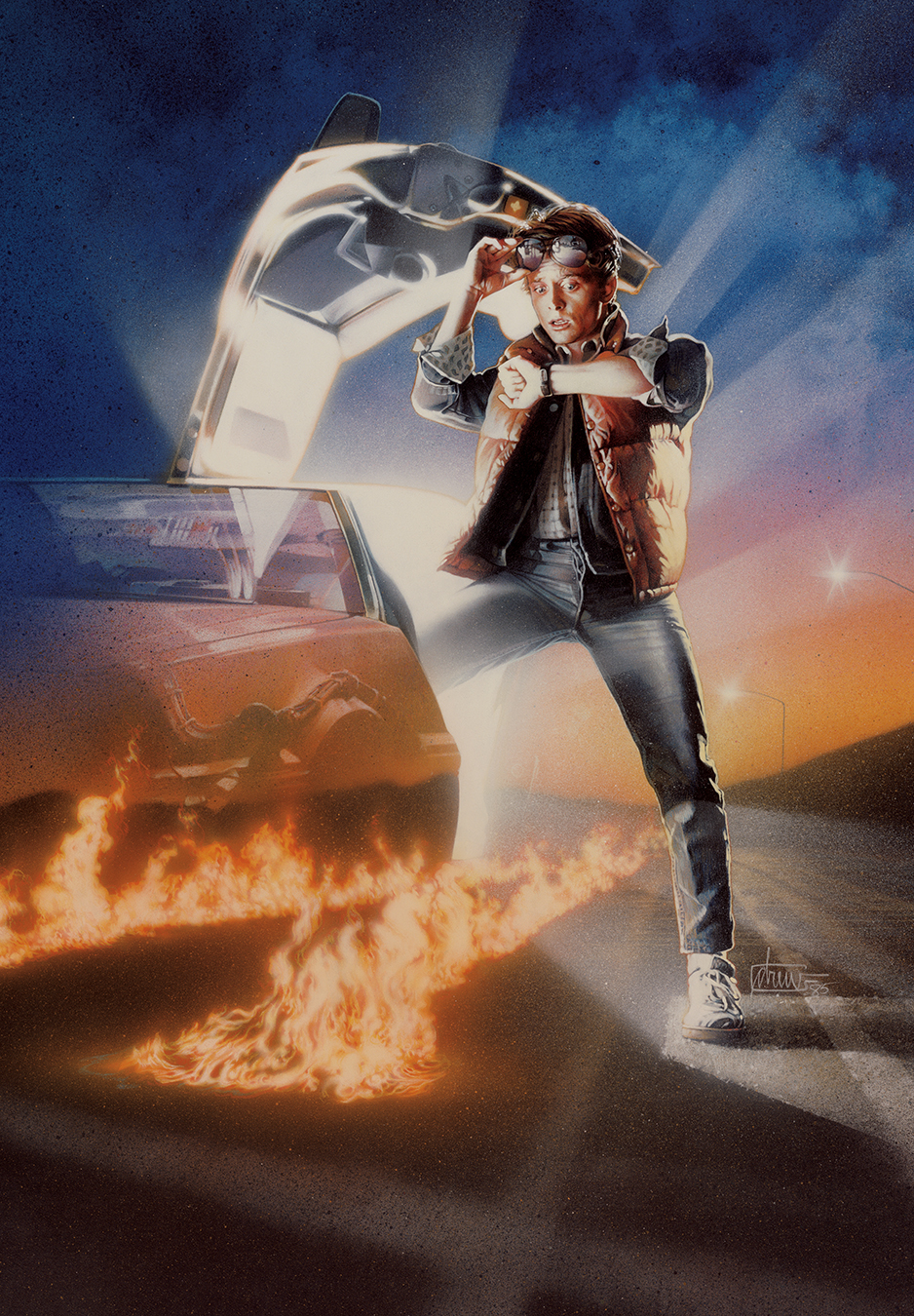

Back to the Future. ©Universal Studios 1985–1990.

-

E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial. ©Universal City Studios 1990.

-

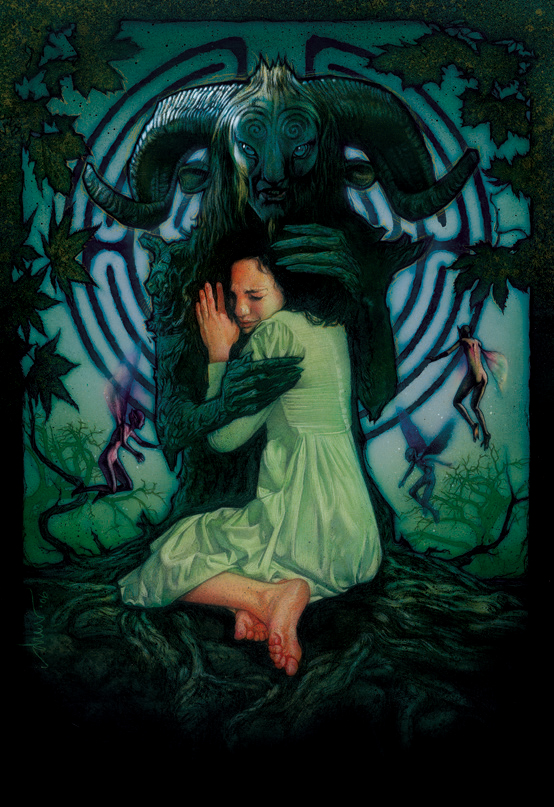

Pan’s Labyrinth. ©Drew Struzan 2006.

Drew Struzan

Painting his way through pop culture and beyond.

Make your way along the Los Angeles Interstate web, a skein of ramps, exeunts in extremis; drivers overtaking you at the speed of sound; passing so many familiar names benignly posted on green highway signs, white lettering spelling out Dodger Stadium, Rose Bowl, the Walt Disney Concert Hall. Exit to Pasadena, to a quiet suburban neighbourhood, sunny of course, but also somehow sheltered and shady in an agreeable way. Past a park, among a row of nicely kept homes, is the residence and studio of Drew Struzan. This is no Xanadu, but something fantastical occurs here pretty much every day, and it would surprise you, should you stroll by on your way to the park, to learn that some of the art produced here is known throughout the entire world.

That, in a way, is a defining characteristic of artist Drew Struzan. His personal life and his work are one with each other, yet seemingly at odds too. He lives in a smallish, nice home, garage to the right as you enter, and out back, a lovely studio. This day, he is taking a cup of coffee with his wife, Dylan, discussing the high probability that the writer from the Canadian magazine will get lost. But they both hit the ground running when the odds are somehow beaten, two very welcoming people discussing presidential races, the weather differences between Canada and California, raising children, that sort of thing. Then Dylan gracefully excuses herself, and what ensues is not so much an interview as a demonstration of how a good conversation is the operative definition of starting something you can’t finish. Nor, in this case, would you want to. Drew Struzan is not one for small talk, really, and so we are off.

How did it begin? “I always knew I would be an artist,” he says. “I was even checked, medically, as a kid, since my eyes seemed a bit different, or at least the way I saw the world was different. Turns out, in fact, I see things with some kind of mild 3-D effect—my depth perception is different. So is my perception of colour. I seem to see richer, deeper tones, more vivid. It is not a unique condition, but for a young guy wanting to be an artist, it was simply a confirmation, to me, that this was meant to be.” He sits under a comfortable canopy in the backyard, but the energy he exudes, at once calm and implacable, is impossible to resist. “As a young man, with a baby in my arms, I went to various employment offices looking for work. My wife was holding down a steady job, was the breadwinner as they say. One day, I just asked someone, ‘Do you have postings for artists once in a while?’ ” He smiles, leans back in his chair a bit. “The answer was, ‘Rarely, but yes, and in fact someone posted one yesterday.’ ”

That someone was from a record company, and they needed an artist for album covers. In those days, album covers were a bigger deal: the records were issued on vinyl, and the art was 12 by 12 inches, not the five by five of today’s CD booklets. “It was interesting work, but I knew it wouldn’t be enough. How many album covers, at $150 apiece, do you need to make a living? But then a movie producer called and asked me to do a poster, which I did. Then a few more. And all this time I was doing my own art, as well. Not a lot of spare time.”

The serendipity of it all is, in retrospect, overwhelming, seemingly ordained, as those B-movie posters led to work on another, much higher profile film.

At this point in cinematic history, George Lucas had done an alternative, experimental film, which did a paltry box office, and then a paean to fifties and early sixties pop culture, which was massive. Then along came Wars.

“The most important thing for me is to have people see my work, to participate in it, to like or dislike it—and to engage in it. This, for me, is what art is about. Not isolation, doing something in a room and never showing it to anyone.”

“I got the [Star Wars] job from a fellow artist, Charlie White,” says Drew. “He got the commission to do a Star Wars re-release poster. He was a marvellous painter, but did not do portraits. He asked if I’d like to ‘share’ a painting with him—I’d do the portraits and he’d do the robots.”

Lucas, who, after all, seems to have some kind of instinctive finger on the pulse of popular culture, and is in fact an artist himself, later said, “I like to think I am reasonably sophisticated about art—that I have an eye for what is good and for recognizing talent when I see it. When I first saw the illustrations of Drew Struzan, I knew that his work was special and conveyed a sensibility, artistic flair and dramatic depth that would fit perfectly with the characters and films that I had created.”

Drew’s work on Star Wars was soon followed by a lengthy series of recognizable pieces of movie art: Back to the Future, the Indiana Jones series, the Harry Potter films, Blade Runner, E.T. And on it goes, a collection of images deeply and popularly ingrained. Drew has been a part of all these, and in the process left an indelible mark on the history of Hollywood cinema and on pop culture.

Although the posters are an essential component of advertising campaigns, the movie marketing system is not part of Drew’s vision of art. He invests his time and his ability in movie poster art because it is part of his understanding of the world, and of art’s place—its role, even—in the world. “The most important thing for me is to have people see my work, to participate in it, to like or dislike it—and to engage in it. This, for me, is what art is about. Not isolation, doing something in a room and never showing it to anyone.” He leans forward. “The reason I am an artist is that I want to look at the world, take it in and tell the truth. So for me, art comes from inside yourself. You try to express an emotion in a painting, in all its nuances and subtleties, in order to express truthfully what you see and feel.”

Throughout the conversation, Drew often makes mention of his understanding that his abilities and his work are part of a greater fabric, in the sense that while he is a painter, an artist, his vocation is no more valuable or intrinsically noble than any other. The constant theme with him is a modesty that is totally convincing, despite the evidence that he has something truly special in his skill set. “It’s just me doing what I need to do. The most important thing is just to be true to yourself, to not simply be reactive to the world at large, but allow it in and then make it your own. That is what everyone tries to do. And from there, in terms of artistic expression, you try to be unique, uniquely your own.”

Drew’s studio is a few paces from the back door of the house, and is of a piece with the architecture of the place. But once inside, it is as if you have entered an entirely different world. There are easels, with paintings in various degrees of progress upon them. There are finished works that have not yet found a home, or are soon to be on their way. There is a narrow shelf running the entire circumference of the room—for it is in fact a single room—and on that shelf are some remarkable pieces. There are early mock-ups of Indiana Jones, an image of Mickey Mouse, E.T., various portraits that became larger artworks.

Sacrifice. ©Drew Struzan 1996.

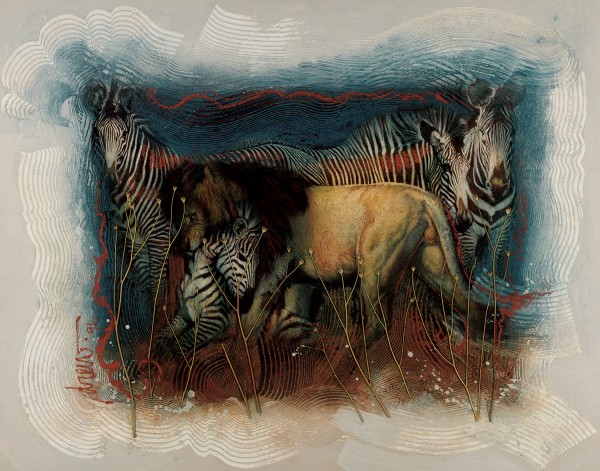

Drew usually works on poster art at around 27 by 41 inches (the same size as the end result), and his personal works can range from half to twice that size. So there is a visceral impact upon seeing them, an understanding of how he strives to achieve that effect on an audience. Sacrifice is a case in point. It is a striking, vivid and unnervingly mimetic painting in which a lion stands proudly with a dead zebra in its mouth, a surrounding herd of zebras calmly ignoring the fate of their comrade. It is oddly moving, evocative, and the emotional states of all the creatures achieve, in ensemble, a profound morality tale. “I showed this at a gallery once,” says Drew, “and someone brought a group of patients from a psychiatric facility to see the show. One patient looked at this painting, and then shouted out, ‘That’s exactly what those bastards are like. They don’t care.’ I found that extremely moving, that this person would engage in the painting on that level. That, for me, is what it is about.”

Filmmaker Guillermo del Toro, who knows well this motivation and approach to process, commissioned Drew to work on a poster for Hellboy, and asked him to create a piece of art for his great work, Pan’s Labyrinth. “What Drew does isn’t really distilling the elements of a movie,” says del Toro. “It’s almost alchemy. He takes images and makes them quintessentially cinematic. His style has been copied so many times in a bad way, people don’t realize until they revisit his posters just how powerful the pure Struzan style is.”

There is no motivation to do movie work at this stage in Drew’s career. “The paintings for Hellboy and for Pan’s Labyrinth, they weren’t used by the studios as the posters, as they were designed and intended for,” says Drew. “So when Guillermo asked me to do the second Hellboy, he was reluctant after their non-use of the first Hellboy poster, but wanted it even if the studio did not want to use what we did—and they didn’t. Universal conducted the market research on the poster, and they received the highest approval rating they ever got, and still never did use that art. The studio didn’t like it. At a press conference in Europe, a reporter asked why my art was never used for Hellboy II, and the answer was, ‘Because it looks too much like art.’ So I knew then it was over for me, because I don’t make those kinds of distinctions. After a lifetime of working to make art out of advertising, there appears to be nothing left for me to do.”

Yet it remains, unquestionably, that whatever struggles exist, Drew’s works are one of a kind, to a point that’s all too clear to the veritable superstars in the film industry. Director Frank Darabont, for whom Drew created posters for The Shawshank Redemption and The Green Mile, sums it up: “Most of what passes for movie poster art these days are just Photoshopped pictures of actors striking saucy poses and staring at us like a troop of lobotomy victims. Drew’s work speaks to me on a much deeper level. The images he renders become part of that film’s iconography and history.” Steven Spielberg has an appreciation of Drew that is direct, immediate: “Drew Struzan’s artwork makes such a promise of grand entertainment that he puts tremendous pressure on all of us directors to keep that promise.” You might think all this praise and such illustrious company would affect Drew, but you would be wrong. He does the work with a purity of intention and execution that make him unique, an artist expressing the truth of what he sees and sharing it with his audience.

In the Struzan living room is a piece of Drew’s called Green Jungle, intimidating, evocative, dramatic, mesmerizing. In the Struzan kitchen is a refrigerator, with a rendering of The Last Samurai. The brown tone of the art is perfect for the kitchen’s demeanour. These are, in sum, the parts of the whole of the art universe that is Drew Struzan. He does not distinguish between fine art and popular art, but rather thinks of art as a mode of expression, and therefore as communication. So while he may not be coming soon to a theatre near you too many more times, if at all, he remains a prominent part of the cultural fabric. And he still has a thing or two to share.