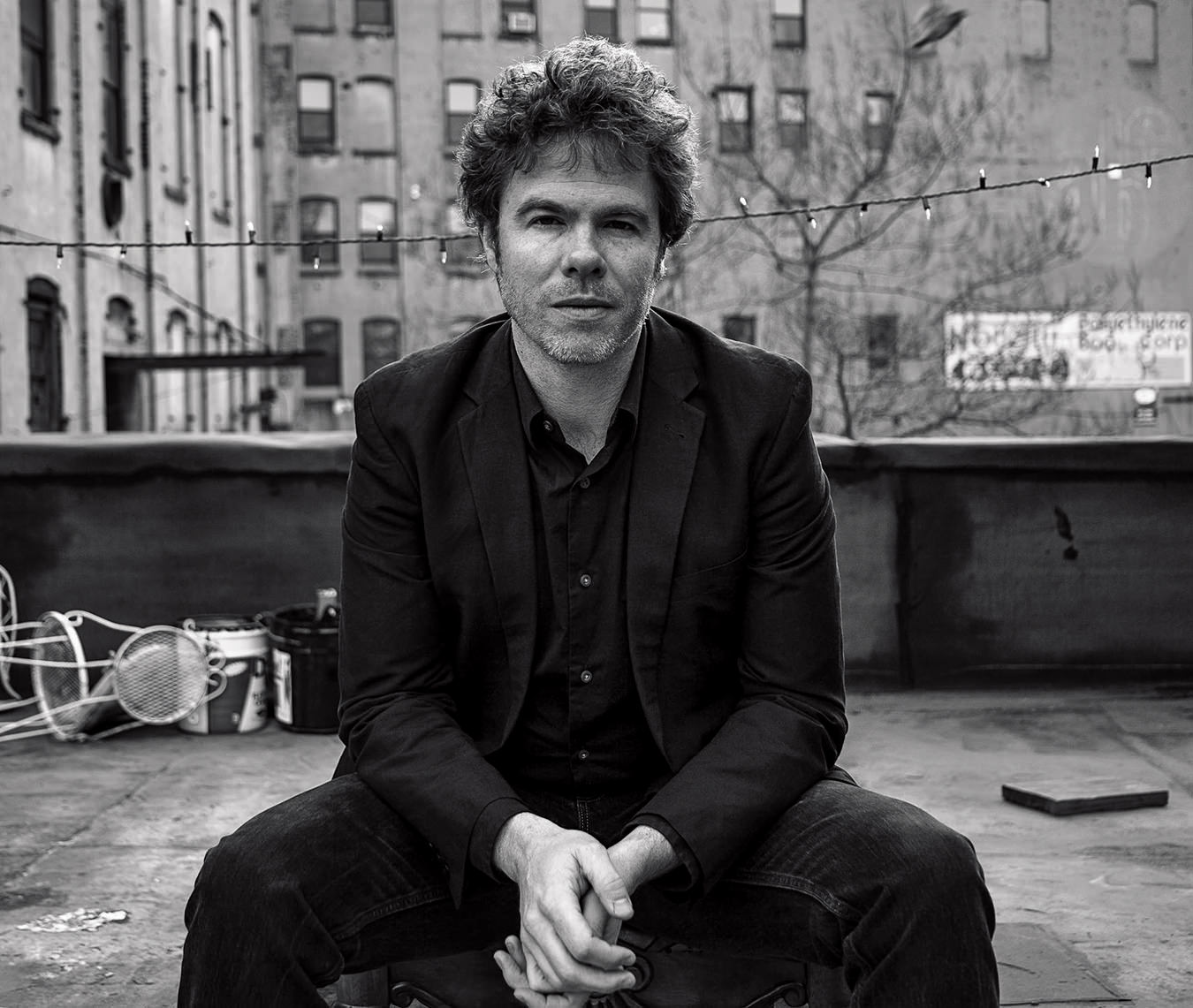

Daniel Lanois

Soul-mining music man.

Late-afternoon sunlight is flooding Daniel Lanois’s studio in downtown Toronto. In front of the ivory leather couch that we’re sitting on is the most impressive drum kit I’ve ever seen. Beyond that is his pedal steel guitar (he calls it his “church in a suitcase”), and just over his shoulder is a red piano topped with awards. The rest of his awards are in L.A., where he lives when he’s not in Jamaica or somewhere in Europe. At the end of the room is the mother of all mixing boards. I’m in musical Shangri-La.

Lanois has a warm smile and eyes like dark-chocolate pudding. When he sits down beside me, humming bass lines, I try to remember why I turned down the champagne he offered when I arrived.

If you don’t know his name, you definitely know what he sounds like. The French-Canadian musician has produced records for Peter Gabriel, U2, Willie Nelson, Bob Dylan, Emmylou Harris, Ron Sexsmith and the Neville Brothers, to name just a few. He’s also made some of his own, accumulating 10 Grammy’s and five Juno awards in the process.

He began making records in the early 1970s in Hamilton. He and his brother Bob had a studio in their mother’s basement. “I wasn’t really called a producer then,” he says. “I was just a guy running a studio, being helpful. We were connected with the Gospel Association of Canada. They brought artists from all over the world, and my mom’s basement was one of their stops. They were usually quartets. That was a big part of my education: being constantly exposed to the harmonic interplay of four parts.”

Meeting and working with Roxy Music keyboardist Brian Eno encouraged Lanois to dig deeper into the garden of sound. Together, they made experimental ambient music, which led to an invitation to work with U2. Lanois and Eno co-produced The Unforgettable Fire in 1984 and The Joshua Tree in 1987, the latter winning a Grammy for album of the year. Later came production credits on Achtung Baby, All That You Can’t Leave Behind, and How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb.

I ask about another impressive endeavour, performing at Carnegie Hall; he’s played there twice. “Carnegie Hall was great,” he says, eyes lighting up. “The first time was with Emmylou Harris and Daryl Johnson, who is a great singer. We did some lovely three-part harmony. The big hall is an echoey place, and choral music sounds best in there. I did a rock show in the smaller room—again with Emmylou Harris as my guest.”

In 1995, Emmylou’s Lanois-produced album Wrecking Ball won a Grammy for best contemporary folk album. He speaks highly of her. “She is a sweet soul,” he says.

To Lanois, the console is not a piece of technological equipment but a musical instrument, and mixing is a type of expression.

While we’re on the topic of greats, Bob Dylan comes up. Lanois has produced him twice: in 1989 on Oh Mercy, and in 1997 on Time Out of Mind, which won the Grammy for album of the year in 1998.

“That award is impossible to get. I was very proud of that,” says Lanois. “I felt like that record really had a powerful identity. Bob knew what he wanted to say and I knew what records he loved, and I referenced those records, mostly old blues and rock ’n’ roll records. I understood what he loved about them—they had a sense of discovery and urgency. I like the sound of the limited technology of the thirties, forties and fifties, and I made sure Bob got that sound. I found that by having fewer microphones and things happening live in a room, you got an automatic depth of feel—something about the natural geographical space between the players. So we approached it that way and got great natural depth of feel, and a sense of urgency.”

Lanois says that Dylan is one of the most dedicated people he knows: “He’s completely committed to his lyric.” Being in the studio with Dylan, he says, is “just coffee and work, there’s no meanderings. The studio is not a place of ‘Let’s play pinball in the green room while somebody does a guitar overdub’. None of that for Bob. He’s someone who made a big impression on me as I was growing up, and I was happy to be able to return the favour.”

In his autobiography, Chronicles, Volume One, Bob Dylan discusses in detail the time he spent recording Oh Mercy with Lanois in New Orleans. “One thing about Lanois that I liked is that he didn’t want to float on the surface. He didn’t even want to swim. He wanted to jump in and go deep. He wanted to marry a mermaid,” writes Dylan. “He slept music. He ate it. He lived it. A lot of what he did was pure genius. … He stood in the bell tower, scanning the alleys and rooftops. … He was like a doctor with scientific principles. I asked him once ‘Danny. Are you a doctor?’ ‘Yeah, but not of medicine,’ he smiled.”

Lanois’s feature-length film Here Is What Is recently premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival. The packed house hollered, clapped and laughed in praise. He’s produced and composed movie soundtracks before (including Birdy for Peter Gabriel in 1984 and Sling Blade in 1996), but this project has his fingerprints all over it. The film (for which he is a co-director and co-producer) documents a year and a half of Lanois at work, along with some antique footage, and performances and appearances by Garth Hudson, Sinead O’Connor, Billy Bob Thornton and many others. The film is about the creative process, and gracefully explores the source of art.

The film’s title is based on a Jamaican proverb: “Don’t look to tomorrow, look to right now.” To Lanois, it means that it’s important to maximize what’s available to you. “Those islands don’t have everything,” he says. “But they’ll have something that’s fresh. Maybe it’s a mango or maybe it’s a fish, and that’s what will be in the meal of the night. It’s the opposite of having an endless source of options.”

We discuss a scene in the film where Lanois is sitting in front of a console demonstrating how he mixes a song, and his whole face lights up as we talk about it. This is when he’s at his best—talking about making music, the thing that he eats, sleeps, breathes and loves. To him, the console is not a piece of technological equipment but a musical instrument, and mixing is a type of expression. Beyond working the technical equipment, Lanois’s skill as a musician is his greatest asset in the studio, allowing him to communicate with the players. His approach has always been to maximize the talent and potential of the people in the room, which, he says, is more important than bringing others in.

Lanois uses the term “soul mining” to describe what he does. “Soul mining suggests you have to roll up your sleeves and find a fragment—a lyric or riff of a song that resonates with you. Once you’ve got that gem out of the ground, you need to cut it and polish it and place it and have it be appreciated.”

Lanois uses the term “soul mining” to describe what he does. “Soul mining suggests you have to roll up your sleeves and find a fragment—a lyric or riff of a song that resonates with you,” says Lanois. “Once you’ve got that gem out of the ground, you need to cut it and polish it and place it and have it be appreciated. Soul mining is about the centre. It’s about your discovery—going down the shaft and being driven by possibilities. That’s always been my main interest because I understand the value of the centre of the bedrock. What I talk about in the film is what we get up in the morning for, what we’re excited about.”

After the film premiere, at a party in the bowels of the Great Hall on Queen Street West, the summer heat is cooking up the room. So is Lanois. He’s playing guitar and pedal steel, and is joined on several numbers by other musicians, including his sister Jocelyne on bass. At one point he demands silence, and Garth Hudson (keyboard player for The Band) emerges from the shadows and walks slowly to the keyboard. Looking down at the keys, with only his signature white beard visible from under a dark, wide-brimmed hat, Hudson (whom Lanois calls his “Canadian piano hero”) begins to lay down a groove. “How often do you get to hear the great Garth Hudson play?” Lanois calls to the crowd, while his son Simon places a fan next to the keyboard to cool down Hudson and his band. Somehow, I don’t think it’s going to work.

Back in his studio, back on his couch, Lanois strokes his uniquely trimmed facial hair, and the word “conquistador” comes to mind. He says music has been his passion for as long as he can remember. “I had music around me growing up as a French-Canadian kid. My father and grandfather were violoneux [fiddlers]—not professionals, but good players. The music was very melodic, and those melodies stuck with me. Then my parents split up and we moved from Quebec to Hamilton with my mother.”

Lanois remembers experimenting with music at a young age. “I would get one dollar each week,” he says. “One day when I was nine or 10, I saw what looked like a clarinet in a store window—it was actually a pennywhistle—but it cost a dollar. I bought it, and played it and played it. I invented my own notation system so I could remember what I was doing. When people ask me about producing records in studio, I always say remembering is the whole thing—when you hear something nice, you write it down.” He smiles as he glances at the notebook in my lap.

“When I was working with Peter Gabriel in England, I lived in this little bell tower, a room at the top of this beautiful old house. That’s all I did for a year. I’d wake up in the night in a half-dream state and I’d write my thoughts down. At the end of each week—I had Sunday off—I’d look through the book and choose my favourite parts and type them out. It’s a simple work ethic like that which helped me out with remembering things,” he says.

“I love preparation, because preparation is dedication.” Lanois points to the drum kit in front of the couch. “I hand-picked that drum kit—that’s a Black Beauty snare drum from the thirties. The cymbals have been hand-picked—one’s an Italian hand-hammered cymbal and the other’s a contemporary Zildjian, a Constantinople.” He continues to list the components. “I put a lot of time into that drum kit. It took six months of work. This means when a drummer walks in the door, I can speak his or her language. They’ll respect you for it and you’ll get a better performance.”

Lanois’s current projects include releasing a companion record to his film and continuing work with U2 on their next album; he and Eno have been writing with the band. “It’s touching to know that you’re still associated with people 25 years later, as has been the case with Eno and U2,” he says. “There’s something special about entering the arena and having that kind of history behind you. It’s great to be back in the studio with my old compadres.” When Lanois was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame in 2002, Bono paid tribute to him, declaring, “Your country doesn’t need you—we do.”

As I stand up to leave, he bypasses my extended hand, and kisses me on the cheek. With “The Maker” (written by Lanois and covered by many) playing in my head, I leave the studio, and him to his craft—and I have a hunch that before I’m too far down the street, he’ll be back working. No doubt he’ll strike gold; he’s a determined soul miner, after all.

Direction: Sandra Zarkovic. Location: Daniel Lanois’s studio, Toronto.