One on One with Monsieur Hermès

What's in a purse?

It would be easy to consider Hermès not dissimilar from other maisons de luxe. Beautiful packaging, logo and signature product recognition, along with a terrific price tag keep it in line with its alleged competitors. Beyond the superficial, however, resides a philosophy and even a philosopher with a belief in the “exquisite perception of the improbable.” The improbable is the essence of the Hermès product.

This is perhaps why Mr. Jean-Louis Dumas-Hermès, Chairman and fifth generation Hermès, smiles to himself and responds jokingly to a question on whether he’d be willing to undertake such a venture as Hermès anew in 2003: “I would run to an asylum.” He quickly qualifies that he’d immediately “try to find people able to create without too many boundaries.”

Entering the modernist building in Pantin where Hermès houses one fleet of its artisans (1,000 artisans in total are employed), one discovers the fruits of the aforementioned search. The evidence for everything Hermès represents can be found in this Paris suburb, approximately 15 minutes outside of central Paris, where the head office and flagship store are found at 24 rue Faubourg St-Honoré. There certainly appears to be an absence of conventional profit-cost analysis in the making of anything Hermès. A privileged tour with Yorick de Guichen, Head of Leather Development, makes this clear. One artisan will take between 10 and 20 hours to complete a Kelly bag and between 12 and 24 to complete a Birkin. It will take 250 butterflies and the silk from their cocoons to complete one Hermès scarf. The hum from all this activity at the ateliers sheds a new perspective on the theory behind the Butterfly Effect.

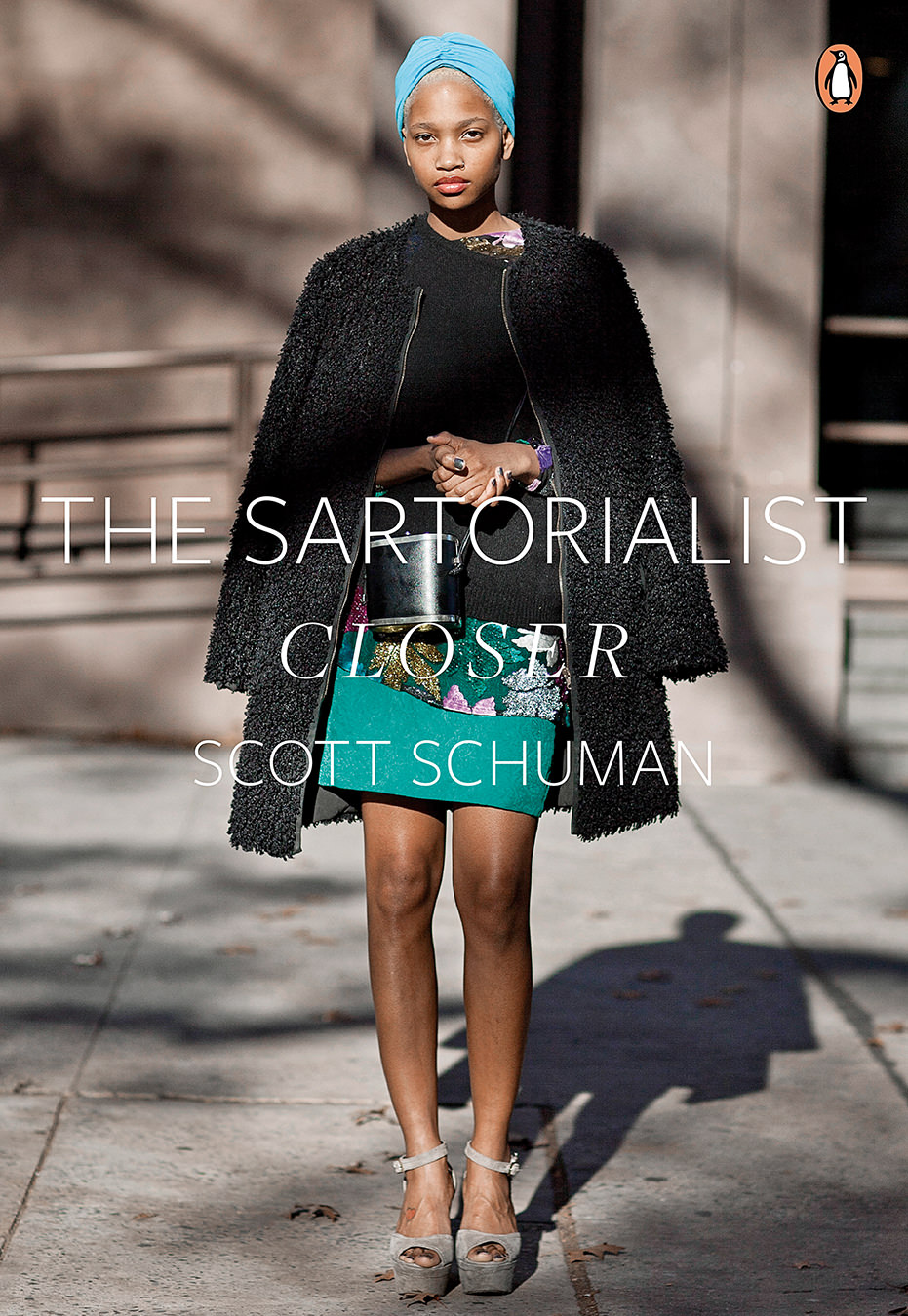

The Birkin 35cm bag, a scarf from Le Mediterranée theme, glycerine soap, H-our or HeureH watch, linen baby shoes. Photo by Clinton Hussey.

The store at 24, rue Faubourg St-Honoré, 1926. Photo by D.R.

The store at 24, rue Faubourg St-Honoré, in 2003. Photo by P.A. Decraene.

The Hermès family began to make leather products in 1837 when Thierry Hermès started his business making saddles and harnesses on the rue Basse-du-Rempart. Leather continues today as the core essence of the company’s goods. What distinguished Thierry’s work was a definition of quality that was his own, a definition of quality which has no point of reference elsewhere. And the company has in fact today become the definitive authority on excellence.

Before the age of 30, Emile-Maurice, Thierry’s youngest son, left Paris to seek out new markets. He gained the Royal Court of Russia’s commission and Hermès became the supplier to Czar Nicholas II. But Emile did much more, so much that he placed the diversification of Hermès decades ahead of its confrères. He expanded the products to include handbags and luggage, travel, sport and automobile accessories (extremely shrewd of a man steeped in the equine tradition), silk scarves (1937), belts, gloves, jewellery, and wristwatches.

Atelier Cuir Pantin. Photo by Johannes Von Saurma.

Today the same exacting standards which won the royal court commission are transferred to each artisan trained into the Hermès family. Yorick explains the role of the Hermès craftspeople and their importance in achieving the Hermès brand of quality; “Every craftsman is different so he gives a different soul to each product. The rationale behind this is that we are working with a material where every skin is different and therefore must have a definition of quality that can adapt.” He explains further, with a subtle yet confident respect and affection for the artisans who make it possible: “The definition is rational, but also emotional,” because every artisan is different. Apparent is the faith and value given to these workers. It is an ethos which permeates the entire Hermès enterprise, beginning with Mr. Dumas, and is perhaps the Hermès difference.

There is no rule, it is a devotion, an obsession for quality with the idea that it can give back the time used to make it and much more.

It is not about the inanimate objects the company creates but about the people who create them. The family Hermès has empowered its artisans with their own creativity. There is no assembly line; “each craftsperson starts from the beginning and ends by signing his creation.” The only boundaries placed upon them, as Yorick explains, is the scarcity of raw materials. A tanner will begin with a group of 1,000 skins which he or she then reduces to 100 worthy of presentation to the Hermès buyers. Of those 100 approximately eight will meet the standards to qualify as a potential Hermès leather good.

It is interesting that Mr. Dumas’ opening strategy of running to an asylum is followed by his comment on creativity without boundaries; it is the very scarcity of these people that in effect creates the ultimate boundary. Yorick comments, “this is the largest scale process we can afford without losing any quality. We are scarcity driven not scale driven.” In other words there is no compromise. If the proper skin cannot be obtained or the artisan properly trained, there will be no product. Fortunately, the artisans trained at the Hermès school stay for their entire careers. They have not only the opportunity to work with the finest skins but also the opportunity to nurture their creative skills and present ideas for new models to the comité de creation where Mr. Dumas himself sits and agrees with the concept, or not.

Atelier Cuir Pantin. Photo by Johannes Von Saurma.

Standing next to Yorick, inside the ateliers, though, imparts a certain incongruity to a conversation on scarcity. The shops seem to be filled with more artisans at workbenches than one would ever conceive for trades work, and the building’s multiple levels promise more of the same. Each area is allotted to craftspeople specializing in their own strength or preference; some have greater dexterity for working with accessories, others greater strength for working with crocodile skins or making briefcases. A workman walks by with yellow Kellys; there are six on his arm. Yet one artisan can only produce two bags per week, sometimes only one, depending on the skin.

Veronique Nichian, the menswear designer for Hermès, has some insightful thoughts on how a company with such a rigorous demarcation for quality can withstand and endure in the 21st century: “C’est pas le business—il s’adresse aux gens qui apprecient et comprennent cela. Il y a toujours des gens qui veulent attendre. Il faut toujours garder tous ce qui vous fait rêver—des marques qui ne se sont pas cedées au marketing. On s’adresse a peu de gens.” It seems improbable that such lofty ideas and philosophically driven goals would make for such a profitable corporation. Nonetheless, such appears to be the situation in le monde Hermès. (The improbable becomes tenable when you create your own world on your own terms. Dumas himself expanded the boundaries of this world when he restructured and strengthened the existing métiers of silk, leather, and ready-to-wear and added enamel, china, baby clothes, gardening gear, silver and crystal to the product range and not least or last of his contributions is the creation of the legendary Birkin bag.) It is this philosophical viewpoint which grants acquiring a piece of the Hermès universe humanity.

It is evident that above all Mr. Dumas has faith in human creativity. Of the incredible employee rewards he is notorious for creating he muses, “It is a question of sharing. Each individual gives a lot and he needs to receive a little more than his salary—respect and the ability to open his mind.” This humbly comes from the man who created what was known as L’Odysée for the employees of Hermès who did not travel for the business. Five hundred and twenty employees in total, 10 employees per week for 52 weeks, embarked on a one week tour of a given country and were told to bring back a “bag of loot”—images, drawings, objects. “It was a beautiful event,” he smiles.

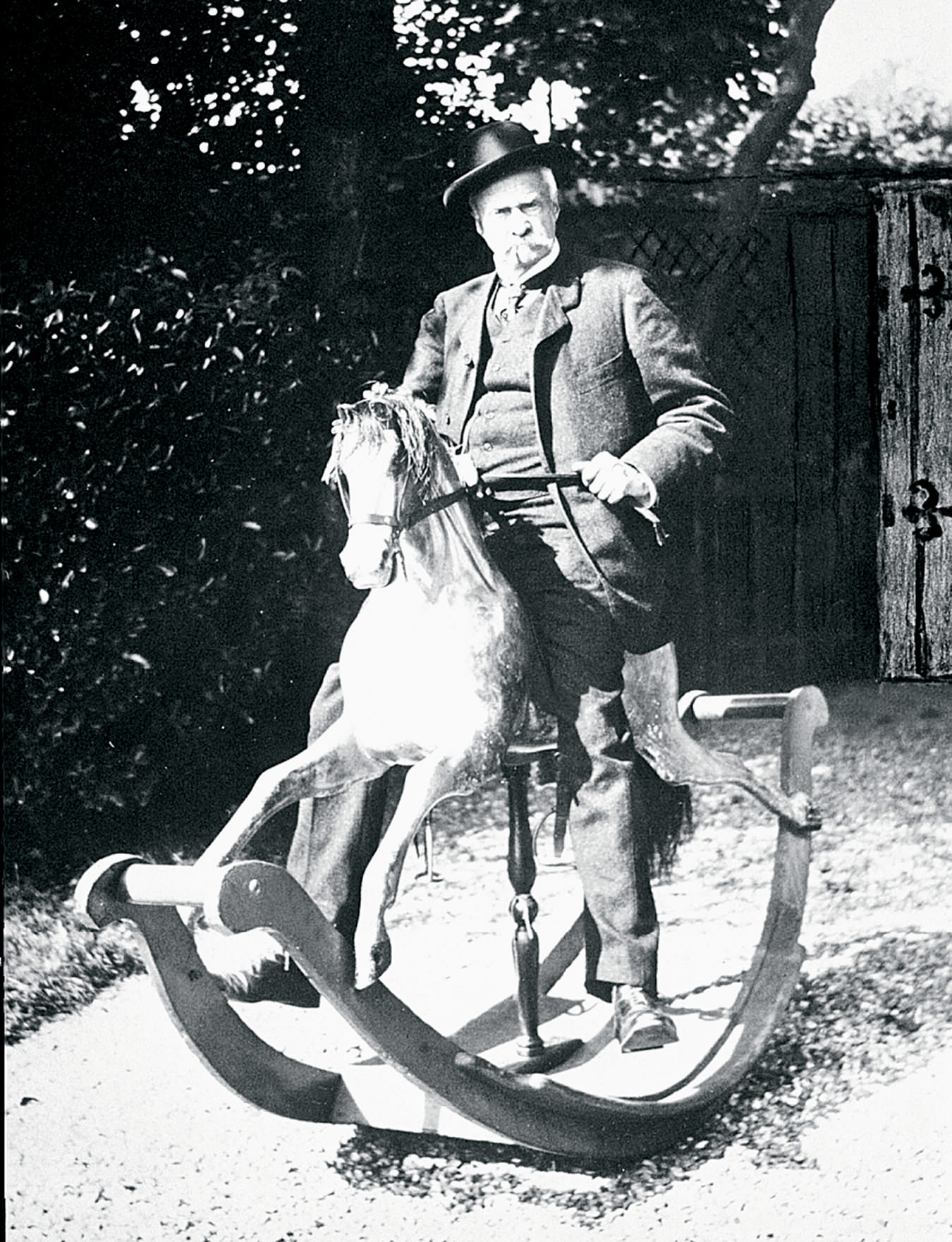

Thierry Hermès (1801–1879). Photo courtesy of Hermès Archives.

Charles Emile Hermès (1831–1916). Photo courtesy of Hermès Archives.

When pressed on how couture for horses could become such a world renown business, Mr. Dumas simply responds “it so happened, it is presumptuous to consider there is a recipe. There is no rule, it is a devotion, an obsession for quality with the idea that it can give back the time used to make it and much more.” Mr. Dumas attributes the longevity of the products to “the intelligent attention to details.” It is in the details that the strength of the product is made, and if it so happens that a leather good must be refreshed during the career of the craftsperson who made it, that piece is returned to the same artisan for adjustments. Everything of le monde is made not simply for the current generation; it is not transitory like much of what exists in the fashion world.

One such detail is the stitching on the bags, rooted in 18th century saddle making techniques. As Yorick points out, “Not much has changed in the way we make our goods.” The linen thread is coated in beeswax to give it strength and a matte finish. This also prevents any water penetration at the seams. The artisan uses two needles and starts at the far end of the bag and works towards himself.

In one particular historic detail Mr. Dumas reveals, despite the insistence on the lack of a recipe for success, that “there is a permanent and visible presence in the genes of the house—the ability to serve this elephant animal”. He brings over a photo of his father Robert Dumas at his house in Normandy, elegantly dressed in tweed. (Robert added ties and perfumes to the company’s legacy as well as cemented their position as unparalleled silk illustrators.) He comments on the sport look of the clothes and digresses into a story about his grandfather Emile. It is the prescience of Emile that played a pivotal role for the house in the 20s. “Canada will always have a special place for me. It was there that Emile discovered, in the cars of the Canadian army, the zipper. He’d been sent there by the French government to buy leather harnesses. There he contacted the engineer who invented the zipper and obtained the right to use it for everything not regarding the automobile.” Hermès leather jackets and handbags with zippers appeared in Paris in 1927.

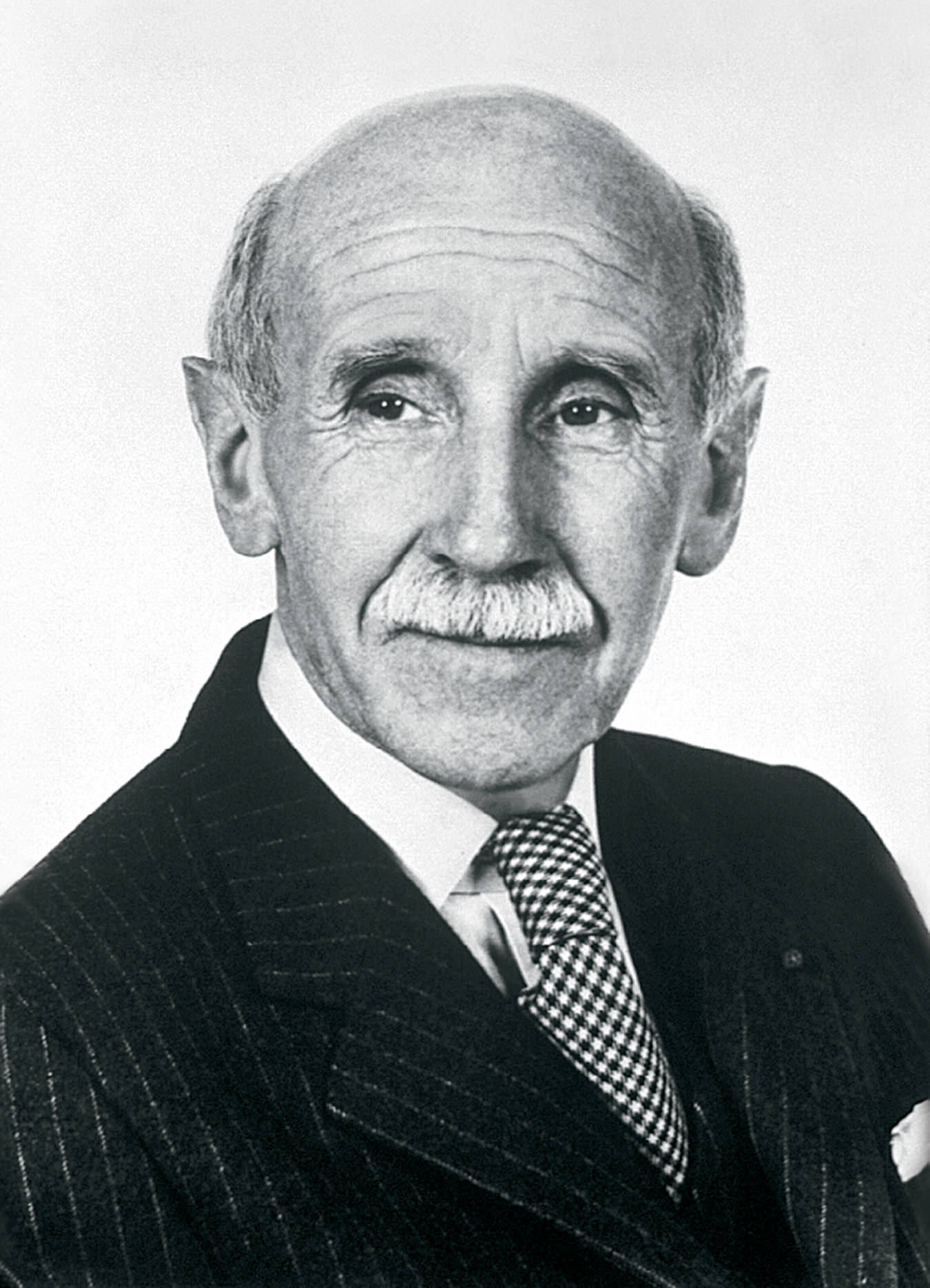

Emile Maurice Hermès (1871–1951). Photo courtesy of Hermès Archives.

And the search for innovation continues as the Hermès team finds ideas from all corners of the earth. They seek it out because innovation in le monde is not restricted to something “new” created at a desk. It is also something unknown. “It is not systematic but in Argentina I met a young woman who was in contact with an Indian tribe in the Amazon. They were making a textile wrapped in natural rubber. We can only assist to help preserve the artisanship in these areas,” Dumas unassumingly explains. The goal is to learn from others, to bring it back to Paris, to incorporate it and then to offer it the world.

Part of this balancing act between tradition and movement forward has been Dumas’ new appointment of Jean-Paul Gaultier as women’s wear designer. Dumas cites continuity as one of his goals. He has successfully brought a family-run company into the world of the anonymous mega conglomerate. Since 1993, 20 percent of the company has been traded publically on the Paris Bourse, while the rest remains family owned and run with eight Hermès family members positioned in various facets of the company. The companies they themselves have acquired or collaborate with constitute the branches for the various métiers in the house: John Lobb for bespoke shoes, Puiforcat for silver, Leica for cameras. Another factor motivating these acquisitions is to preserve the artisanship these houses have established. They could not have hoped for a better protector. Gaultier’s appointment follows logically and naturally since Hermès has a 35 percent equity stake in Gaultier’s company. “Jean-Paul’s creativity and imagination will be a great asset for Hermès, helping us to maintain the elegance in movement which is key to our ready-to-wear style,” explains Dumas.

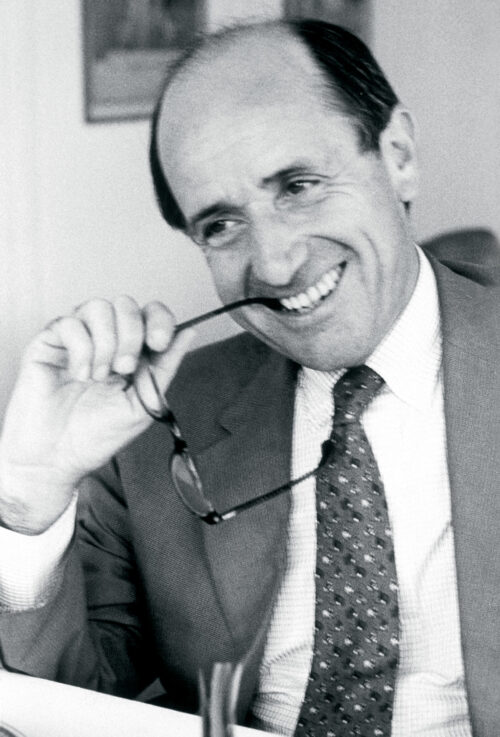

Robert Dumas-Hermès (1898–1978). Photo courtesy of Hermès Archives.

Hermès represents more than the bright bling of a shiny H on the wrist or silk scarf on the arm. In fact, it is one of the few if not the only maisons de luxe where it is not the logo but the object itself which imparts status, to those who can recognize it. This is the subtle difference. Hermès occupies a completely different realm than the brands that have bowed to the gods of marketing. It is a status granted by those who can understand and recognize the work behind the object, the ideals, the tradition, and the beliefs that have made its creation possible.

A cynic may discredit the Hermès family achievements by allowing the price tag to overshadow the work. It is a business venture after all; based on consumption. But the Hermès tradition and vision is a celebration of hard work, a quest for perfection, and a reverence for what the human hand and imagination can produce. In fact, what Hermès attempts to offer cannot in truth be bought. Hermès turns something, no matter how improbable, into the exquisite.