-

The McKinsey Building at the University of Toronto.

-

The McKinsey Building at the University of Toronto.

-

The Schulich School of Business at York University.

-

The Schulich School of Business at York University.

-

The Art Collectors’ Residence exterior, designed to showcase art and allow for maximum natural light.

-

The Art Collectors’ Residence interior.

-

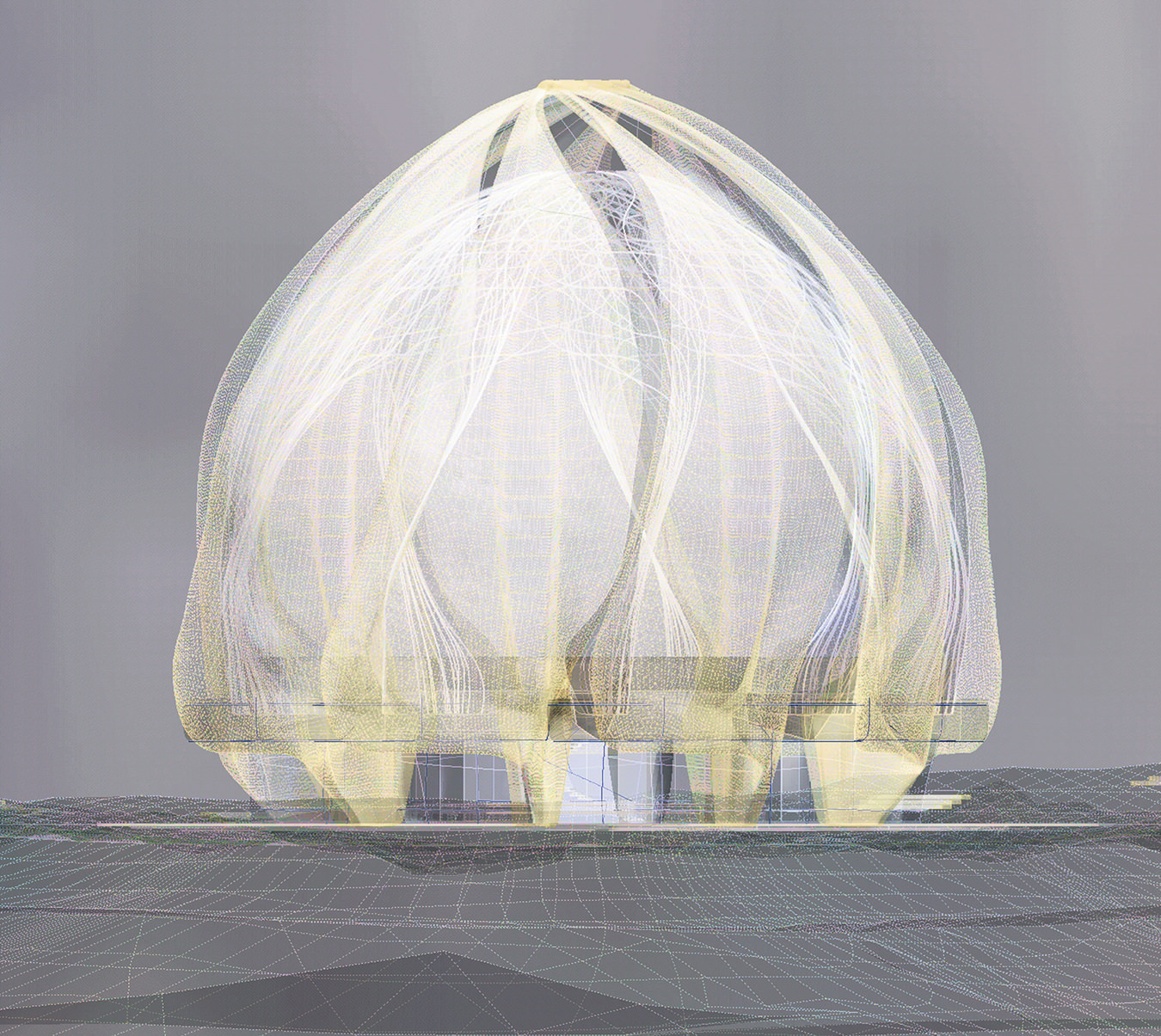

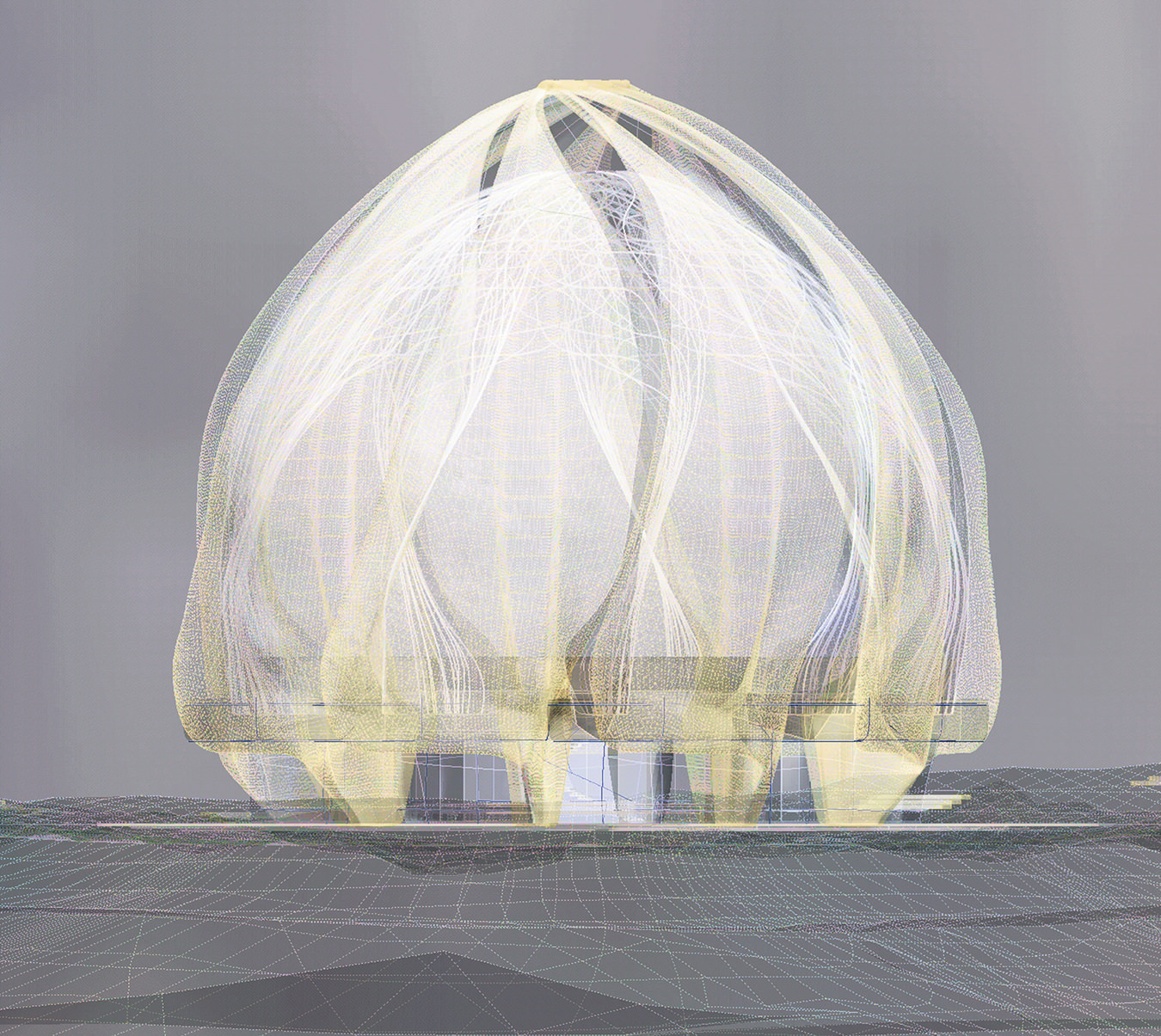

Bahá’í Temple in Santiago, Chile is wrapped in nine “wings”. Light moving between and through each of the wings becomes light-as-structure.

-

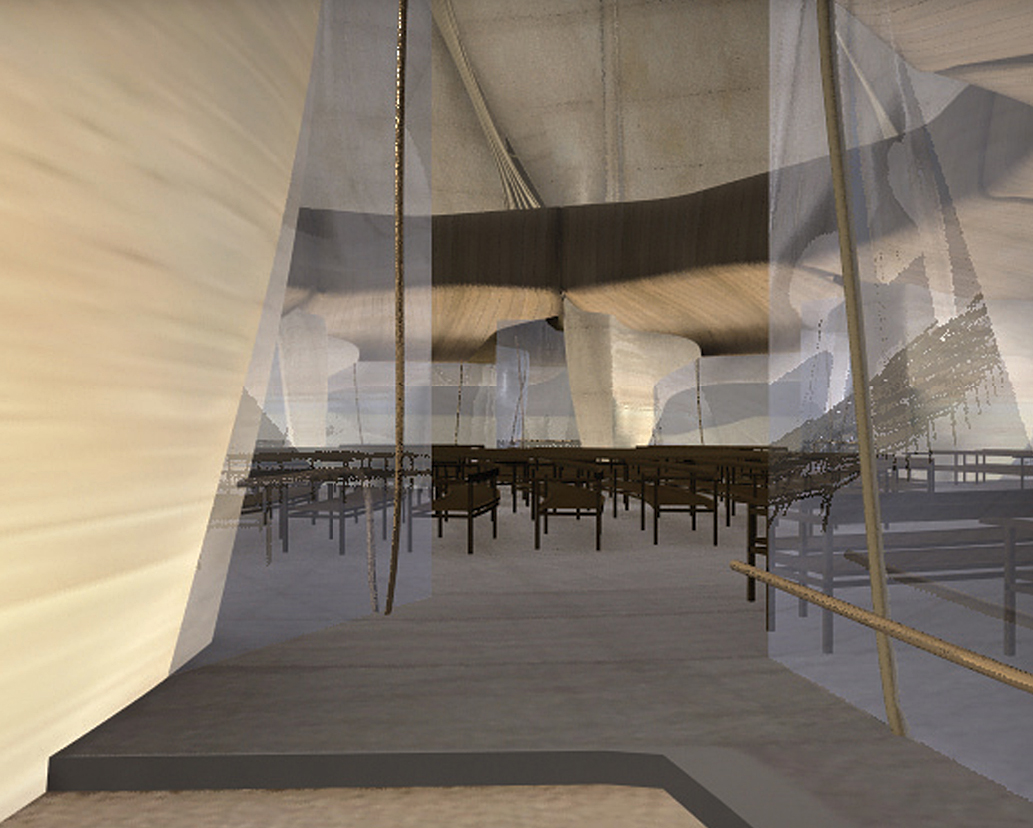

Rendering of the Bahá’í Temple interior.

Hariri Pontarini Architects

Building truths.

The big architectural firms are the ones that get all the attention, but often it’s the small ones that deserve it. There’s no better example of this than Hariri Pontarini Architects of Toronto; in the 13 or so years since the partners established their practice, they have gained increasing international respect for the extraordinarily high quality of their work. Though they avoid the loud and splashy, their insistence on excellence shines through their every project, whether it’s a women’s shelter, a high-rise condo tower, a school or a religious temple.

“We believe in the importance of making buildings,” explains co-founder Siamak Hariri. “We’re not a practice that’s trying to break new theoretical ground. We’re about making buildings. We want to make buildings that sit quietly on the ground.” As co-founder David Pontarini points out, “We get much of our work from referrals. And over the past 20 years, there has been a shift to more design-focused firms. There’s more awareness of design today. We make a deliberate effort to focus on quality.” Though neither Hariri nor Pontarini would want to take credit for this new-found desire for design, they agree it has been a huge boost to their careers. The kinds of projects that are now starting to come their way (condos, specifically) have usually gone to large corporate offices better known for competence than creativity.

From the start, Hariri Pontarini has emphasized attention to detail and the importance of context. They are known for the great lengths they will go to get a building just right. For example, in the course of designing the Schulich School of Business at York University, they employed, for the first time, curtain wall. Although pre-fabricated cladding systems are ubiquitous in contemporary architecture, Hariri Pontarini wasn’t happy with the products available “off the shelf”. Rather than settle for something they didn’t like, they sat down with a manufacturer and designed a new system from scratch. “Curtain wall can be beautiful,” Hariri says, “but you have to gain control over it.”

In an age when architecture has become kind of a “paint-by-numbers” activity—an exercise in assembly more than building—this kind of obsession with the small things has stood the firm in good stead.

Of course, it was the pioneering modernist architect and form-giver Ludwig Mies van der Rohe who famously declared that “God is in the details.” Once his followers forgot that essential maxim, modernism began its long decline into mediocrity. The world that produced Hariri Pontarini was one dominated by second-rate modernists. Mies’s less-is-more philosophy has grown tiresome, not to mention boring and predictable. As much as anything, the rise of Hariri Pontarini is a result of a growing hunger for something new, different and, above all, better.

The project that put the firm on the map, the exquisite McKinsey Building, exemplifies what the firm is all about. The three-storey building was completed in 1999 and occupies land owned by Victoria College at the University of Toronto. Clad in roughcast stone, punctuated irregularly but often with windows, and beautifully finished, this is the office building as country club, and a very elegant country club at that. The term “urban oasis” may be overused, but that’s exactly what McKinsey is. Designed to facilitate interaction amongst employees, it has a spaciousness to it that stands in stark contrast to the strictly hierarchical layout of the typical office building. The central gathering space, which overlooks a garden enclosed on three sides, boasts a fireplace and a pool table, and the attention to materials, especially the stone, speaks of a commitment to excellence. Even in an age of virtual reality, architecture can serve the corporate agenda by creating an image by which we know an organization.

Hariri Pontarini’s building also enters into a dialogue with the surrounding structures, many of which are heritage sites built by the university in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Though it “speaks” to these buildings, it does so without copying them or lapsing into the kind of ersatz historicism that has hobbled so much postmodern architecture.

“We’re not a practice that’s trying to break new theoretical ground. We’re about making buildings. We want to make buildings that sit quietly on the ground.”

After McKinsey, Hariri Pontarini’s next big project was the Schulich School of Business. Located on a suburban campus in the industrial hinterland of northern Toronto, the facility brought a whole new sense of architectural sophistication to York University, something it desperately needed. Indeed, more than any other addition to York, Schulich has helped transform the university from a commuter campus into a genuinely urban precinct. As a result of Hariri Pontarini’s design, the students and staff of Schulich are able to mix and mingle as never before.

“The design makes it impossible not to bump into people and form relationships with peers and professors,” Hariri says. “It’s about forming lifelong relationships.” The building also creates the possibility of a pedestrian realm at York, with a building that seeks to engage passersby with its openness and transparency.

According to Hariri, the big challenge at Schulich was to break down its 260,000-square-foot bulk into something that seemed smaller, what the architect calls a “series of little buildings”. The most obvious example of this is the basic division of elements that includes a low-rise tower on top of a podium. Little wonder the building won the 2006 Governor General’s Medal in Architecture.

Speaking of towers, Hariri Pontarini is now involved in several downtown condo projects that will take the firm’s work, literally, to new heights. Despite being so controversial, the firm’s design for a condo in the ultra-fashionable Yorkville neighbourhood in Toronto is actually well-mannered and thoroughly urban. Its two towers—eight and 17 storeys—sit atop a podium that hugs the ground and defines the surrounding streetscape. The project also incorporates a historic façade, and fills what had been, for decades, a parking lot.

Then there are the small projects: private homes, cafés and the like. Though Hariri Pontarini does fewer of these now, it’s clear that the partners relish the opportunity to get involved in something more intimate and personal. The best recent example is the Art Collectors’ Residence, which was named one of the 12 best buildings in the world last year by critic and editor C.C. Sullivan in ArtInfo.

Situated in an upscale though architecturally-impoverished enclave in the suburban north end of Toronto, the house incorporates what’s best about modernism, but without the dogma that comes with the original. In other words, this is a house conceived more as a series of spaces than as an object on the landscape. It makes a virtue of transparency and simplicity; its lines are clean, crisp and perfectly proportioned. Because this home was commissioned by a couple that collects art, it is designed to allow for maximum natural light; the exterior at ground level is largely glass, as is the pavilion above. “We wanted to build a place for art,” Hariri says. “And we wanted a place for well-being.”

The L-shaped house also includes a stone façade, which is as close to a trademark as Hariri Pontarini comes. Sitting on a heavily treed three-acre property, the limestone exterior and copper and wood detailing allow the building to blend harmoniously with the site. The architects have introduced a note of playfulness to the structure through the straight lines and curves. The effect is subtle, but the sloping roof of the upper pavilion manages to create the sense of a house that soars.

The Schulich School of Business at York University.

Though these designs have won Hariri Pontarini a growing international audience, the project that will launch the firm into the front ranks of architectural practitioners is the Bahá’í Temple now under construction in Santiago, Chile. This remarkable building, which bears a vague resemblance to a mushroom, or perhaps a human heart, is wrapped in nine “wings”.

“These vast wings are made of two delicate skins of translucent, subtly gridded alabaster,” Hariri explains. “Between these two layers of glowing, translucent stone lies a curved steel structure enclosed in glass, its primary structural members intertwining with secondary support members, not unlike the structural veining discernable within a leaf. Light moving between and through each of the wings becomes light-as-structure.”

At once a metaphor and a practical response to an architectural problem, the temple represents a clear attempt at icon-making. It will be a symbol of the Bahá’í faith and a beacon, a sign of organizational and spiritual strength. The translucence of the building, which at night will be illuminated from within, further enhances the spirituality of Hariri’s creation.

The Art Collectors’ Residence interior.

Back in the midtown Toronto office, which has grown to 38 employees, the two partners still sit with their staff. Though each has his own desk, the two share a common table, another symbol of the nature of the practice.

“We rely on each other for mutual support,” says Pontarini. “We play off each other. I think of Siamak more as a brother than a partner.”

“We go back a long way,” Hariri adds. “We both worked at KPMB [Kuwabara Payne McKenna Blumberg Architects] for years before setting out on our own.”

“We both felt we had reached a certain point in our careers,” Pontarini continues, “and we decided we wanted to control our destinies.”

Though the office employs the most up-to-date computer-design technology, both Hariri and Pontarini emphasize the importance of drawing and modelling. Every scheme begins with a blank sheet of paper and a sharpened pencil. From there it goes to the model-makers, who produce countless miniature three-dimensional buildings in aid of the creative process.

“We still rely on hand and intuition,” Hariri says. “Models are more reliable in terms of what you see. We call our model shop our laboratory. It’s where we work out countless problems, both big and small.”

Bahá’í Temple in Santiago, Chile is wrapped in nine “wings”. Light moving between and through each of the wings becomes light-as-structure.

But this is a firm that starts a project not with an image of a specific structure but with a vague sense of what it might feel like once completed. That kind of approach makes it easier to figure out where you want to end up, but not necessarily where you need to start. Through it all, Hariri Pontarini has created a modus operandi that works for them. The vast majority of architectural offices would find this sort of intuitiveness hard to deal with, but one of the joys of remaining small is that staff can take the time they need to do things just right.

At the same time, Hariri and Pontarini are devoted to cultivating relationships with tradespeople who share their dedication to quality. They turn to the same companies and individuals over and over again. For example, in suburban Toronto, Soheil Mosun Limited is handling the fabrication of the wing envelope system for the Bahá’í temple. Visit the warehouse today and you’ll see structural models arranged throughout the building.

“We don’t want to overextend ourselves,” Pontarini says. “But over the next few years, we have a huge number of buildings coming online.”

“We’re all pinching ourselves,” Hariri smiles. “We’ve got some fabulous projects on the go.”

And if it’s true, as they say, that architecture is an older person’s game, there can be no doubt that in Hariri Pontarini’s case, the best is yet to come. Both partners are still in their forties, which makes them positively youthful by architecture standards. They are already looking for larger premises, and the sense of optimism that pervades the office is palpable, and gives a hint as to the marvels that await in their future.

All photos courtesy of Hariri Pontarini Architects.