The SHEE Project

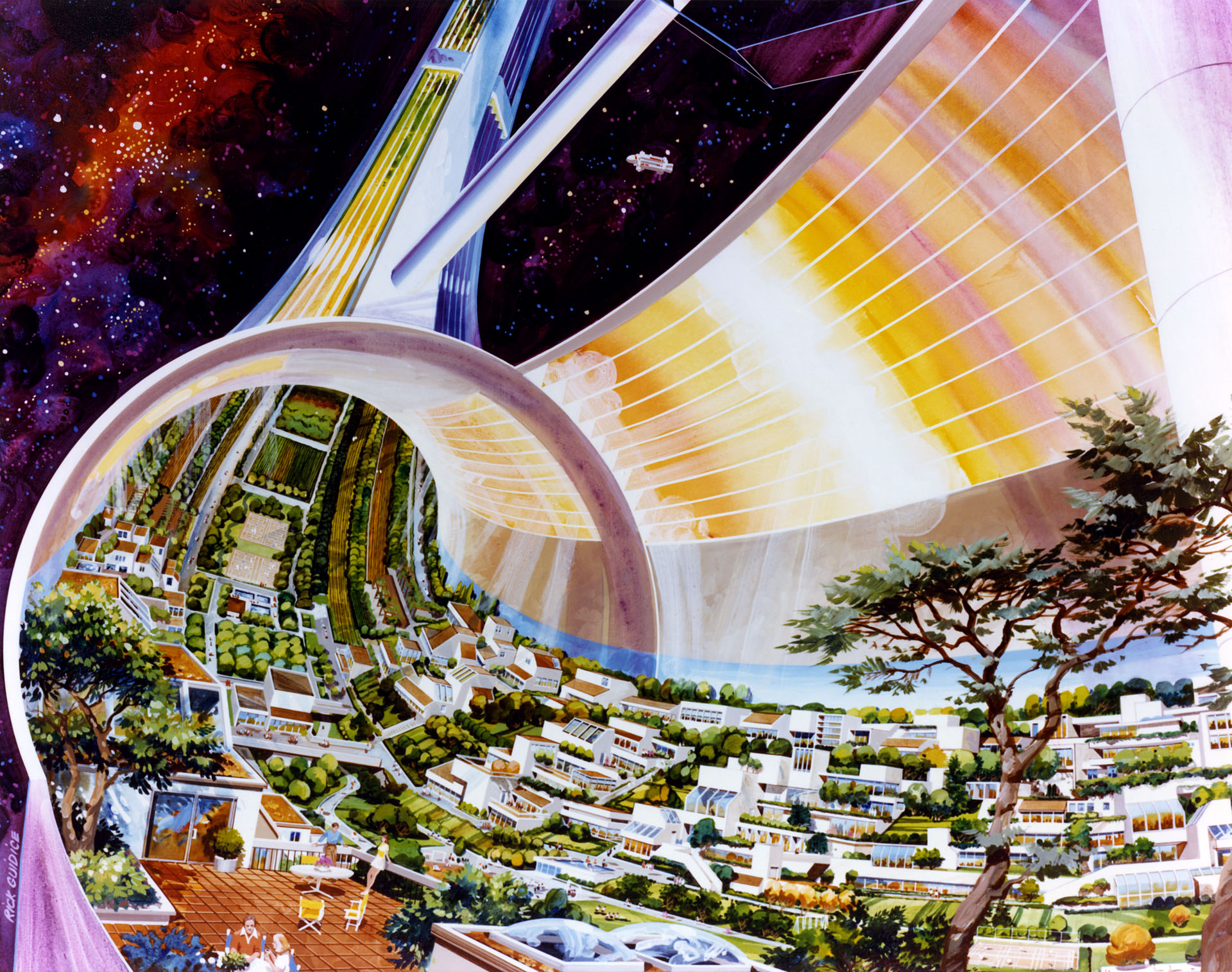

A self-deployable habitat.

Recent films such as Gravity, Interstellar, and The Martian might have you hyperventilating at the thought of reaching for the stars, much less living there, but don’t panic. This winter a European consortium, Liquifer Systems Group (LSG), introduced the Self-deployable Habitat for Extreme Environments, or SHEE. This 300-square-foot live-work space can support a two-astronaut crew in austere environments for two-week test runs on Earth that would mimic short lunar or Martian missions. The shelter is Europe’s first space simulation habitat and the first to use a hard-shell telescope that folds down from its open, “six petal” configuration to become ultra-compact and easily transported by land, sea, and air when stowed, then automatically deploys back out to twice its volume on arrival. It can also be used in extreme environments, from Antarctica to Death Valley, as a research module or emergency medical unit in disaster areas.

The 13-year-old LSG, which did the architecture, human factors, systems engineering, and outfitting of the SHEE, is the brainchild of two women, Vienna-based architect Barbara Imhof and Bangalore-based Susmita Mohanty. These two are among those collaborating across continents, universities, labs, and agencies from NASA, the European Space Agency, and other international space companies. Using human- not machine-focused teams, their designs have ranged from rovers to shelters. “With the emergence of space tourism,” says Mohanty, who earned her multiple advanced degrees in electrical engineering, architecture, and industrial design, “LSG’s multicultural, multidisciplinary approach will become ever more relevant because paying passengers will demand comfort—even style—and will not put up with over-engineered, under-designed habitats or ferries.”

The SHEE demonstrates the direction in which the design of such habitats is headed: toward highly mobile, modular, expandable, and adaptable, converting from habitat, lab, office, or residence to cargo hold while remaining impervious to noisome elements like radiation. Second-generation space habitats will even be made from “local resources” and solar-sintered, or “lava cast”, from lunar sand or Martian regolith.

The blurring of virtual and physical space will become essential to well-being. “With advances in technologies in every major company from Google to Facebook, physical space and the virtual will merge,” Imhof says, “and that virtual space will become an effective extension of the real.”

Imhof describes space habitats that are soft and flexible, with technologies embedded more transparently into their structure. And into the structure, so to speak, of humans too: “Humans are being born into the digital world now,” Imhof says, “so their handling of that world will be very different from ours. To us, it still feels like an add-on because we remember the time without these technologies, but to those who will explore our solar system and universe in the future, the digital realm will seem as real to them as our physical world feels to us today.”

Photos by Bruno Stubenrauch, 2015, SHEE consortium.