-

A view of the Volksgarten, museums, and parliament building. Photo ©WienTourismus/Christian Stemper.

-

Vienna’s Ringstrasse is a 5.3-kilometre-long, 57-metre-wide boulevard. Photo ©WienTourismus/F3.

-

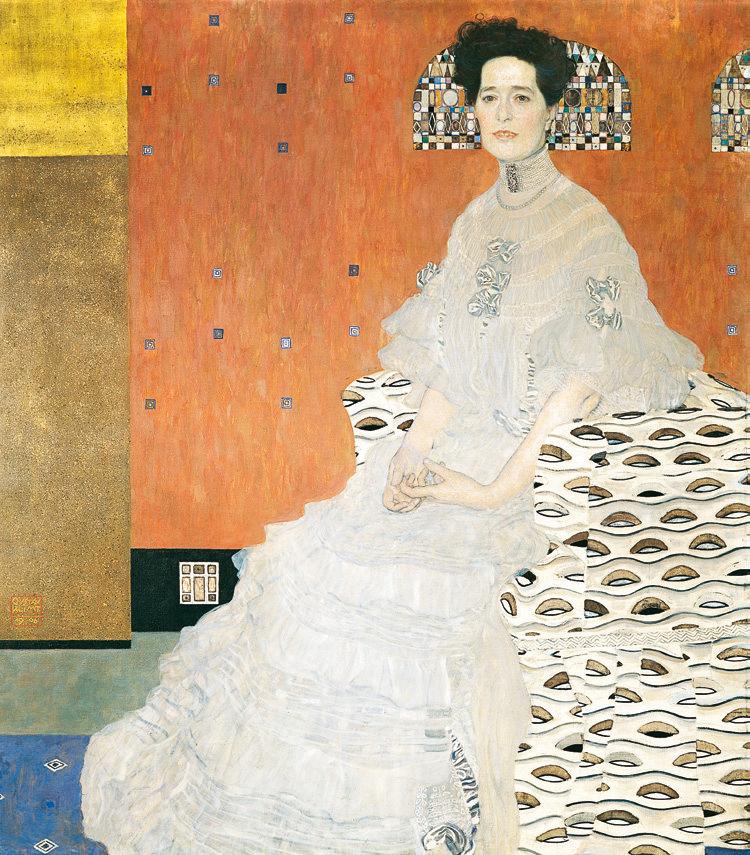

Burgtheater is a statue-rich 1888 edifice with staircases painted by Gustav Klimt. Photo ©WienTourismus/Heinz Angermayrmax

-

The view from Burgtheater to the Ringstrasse and Votive Church. Photo ©Popp & Hackner, courtesy of WienTourismus.

Vienna’s Ringstrasse

Party ring.

Paris had the triumphal Champs Élysées and London the stately, tree-lined Mall. But in mid-19th-century Vienna—seat of the historic Habsburg monarchy—there was only a faded tangle of old-town streets circled by military towers. And for Emperor Franz Joseph I, that wasn’t good enough.

“He wanted to turn Vienna into one of Europe’s most outstanding capitals,” says Alfred Fogarassy, editor of Vienna’s Ringstrasse, a photo-packed new tome marking the 150th anniversary of the official opening of the city’s circular grand boulevard. As the Ringstrasse—a 2001-designated UNESCO World Heritage site—took more than 50 years to complete it feels like a greatest-hits record for architecture buffs.

Alongside dozens of delightful, filigree-accented palaces and government buildings, there’s the eye-popping, Greek temple–style Austrian Parliament; the breathtaking Neo-Renaissance Vienna State Opera; and the twin jewel boxes of the art and natural history museums, twinkling at each other across the statue-filled gardens of Maria-Theresien-Platz. But while dozens of architects were enrolled in the drive to transform and upgrade the old city, Vienna’s medieval history wasn’t forgotten.

“My favourite building is the Akademisches Gymnasium,” says Fogarassy. “Designed by Friedrich von Schmidt, it proved the suitability of Gothic architecture for modern purposes.” Indeed, von Schmidt’s design was so successful that he was also commissioned to build Vienna’s new Rathaus city hall, a turreted Flemish Gothic masterpiece that’s now a firm favourite with Ringstrasse visitors.

This open-air museum of landmarks enthralls today’s camera-twitchers—few stray far from the 5.3-kilometre-long, 57-metre-wide boulevard—but the Ringstrasse project wasn’t popular with everyone when it began. But while the Emperor required every drop of influence to realize his dream, the project also had unintended consequences.

Workers flocked in from across Europe, increasing Vienna’s population by 30 per cent between 1857 and 1868. With this influx of people came a bold new elite. Dozens of Ringstrasse coffeehouses also popped up, becoming raucous exchanges for the artistic, cultural, and political communities—a catalyst that would soon propel the careers of Gustav Klimt, Sigmund Freud, and many others.

As independent thought flourished, the monarchy, challenged in other parts of Europe, began to fade in relevance here, too. But when the 86-year-old Emperor died in 1916, content that his monumental vision had come to fruition, The New York Times reported that 200,000 Viennese lined the funeral procession. Aptly, the slow-moving horse-drawn carriage trundled along a section of the Ringstrasse.

Austria’s monarchy was dissolved two years later, but Franz Joseph’s grand legacy seems like it might be forever imprinted on the city.