Rufus Wainwright

Flip Flops on 5th Avenue.

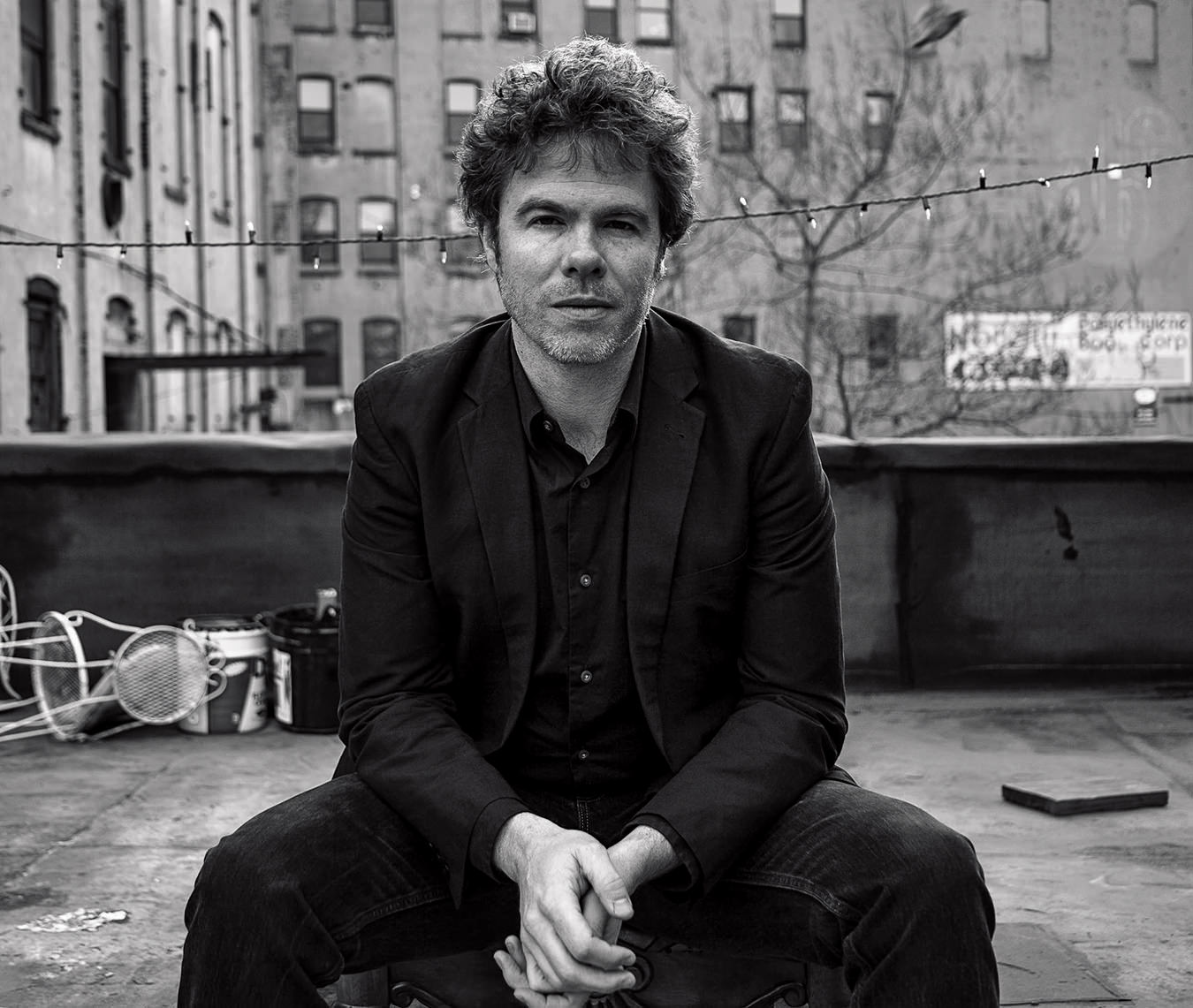

Misfits and misanthropes are lined up around the block. The queue of fans waiting to meet him snakes out of the record store and along the downtown street. Some clutch digital cameras, others bear roses to offer and albums to have him sign. All hope to shake his hand, smile at him, softly say they love him; share stories about that time they almost met behind the stage door, about his music changing their lives.

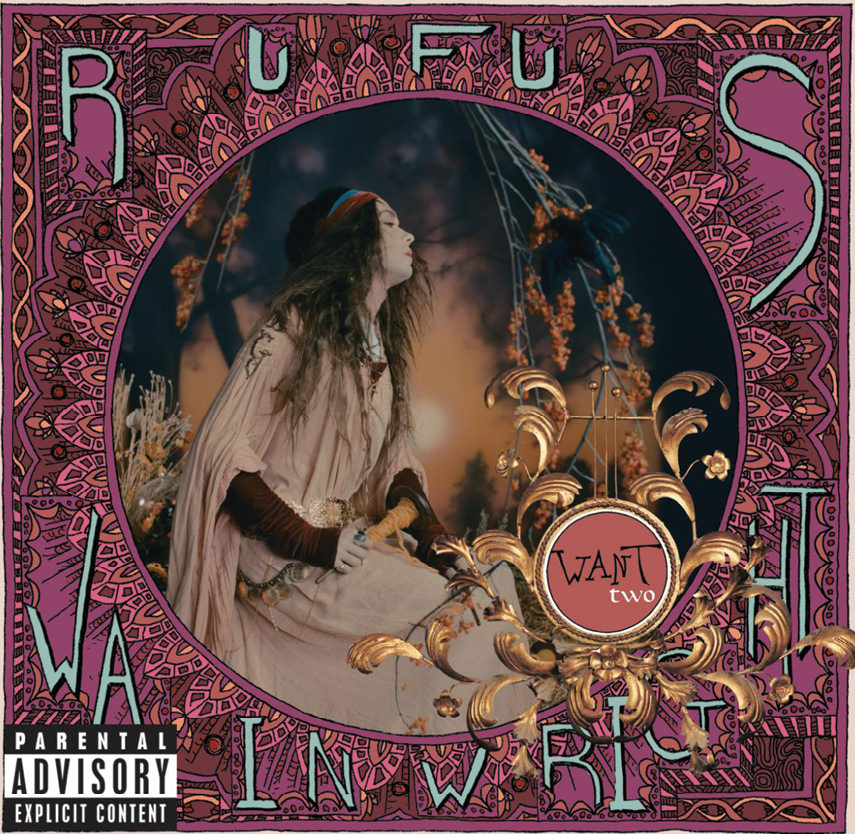

It is last April. Singer, songwriter and multi-instrumentalist Rufus Wainwright, already an icon at the age of 31, is in Montreal for a concert and autograph session in support of his third full-length release, Want One. Both dramatized and humanized by his theatrical operatic, folk, and classical sensibilities, the lush, orchestrated record, which he will describe to me as “a triumphant statement about my personal struggles with life as a crazy artist type,” will prove to be Wainwright’s best-selling and most critically-acclaimed album to date. That is, until Want Two comes out. Due to the sales concerns of a panicky recording industry, the release date of Want Two, containing the Want sessions’ “more daunting, operatic, and weird stuff,” was pushed to the tail of 2004. Packaged with a live DVD filmed at San Francisco’s Fillmore Auditorium, it will also do very well.

“It’s the end of the Want era,” he will later confide with a campy sigh. “But there might be some runaway hits. Often, records you just release without expectation all of a sudden explode.”

And explode it did—but not just yet. The year is 2003, President Bush has invaded Iraq, and liberal-minded Americans are saddened by the direction in which their country seems to be headed, Wainwright included. Although he lived in Montreal between the ages of three and 24, where he was raised and trained as a musician alongside sister Martha by his folk singer mother, Kate McGarrigle of the McGarrigle Sisters, Wainwright is a New Yorker. In fact, he just bought a 425 square-foot apartment in the trendy Gramercy Park neighbourhood.

“I love New York, it’s still the greatest city in the world, and I’d find it very hard to live anywhere else,” he says. “But there’s a battle going on. It’s tough, but I feel it’s important that I’m there, that I’m part of the struggle … ‘cause, you know, they’d all perish without me! There are some angry forces at work, so I’m placing my faith in all that’s great about this country and hoping the truth shall prevail. At this point, that’s all we can really do. I’m personally terrified that there aren’t more artists who are vocal about politics. I certainly don’t go on the campaign trail or anything like that, but there is a great, and presently-neglected, history of songwriting being intimately linked with social justice.”

Sequestered in HMV’s basement, I too am waiting for Wainwright, who is scheduled to arrive through the store’s not-so-secret underground entrance. He will tackle our television interview, greet his followers, then dash off to sound check for this evening’s show. Meanwhile, suspecting that inspection of aforementioned fans might provide some insight about the man, I locate my cameraman and investigate.

The queue outside is still growing; a patient army of devotees representing every shape, size, and social disposition. Catching my eye are three pretty teenagers, two boys and a girl, wearing school uniforms and positioned at the line’s midway point. They look to be about 16.

“So, what brought you out today,” I inquire nonchalantly, batting my eyelashes and shoving a microphone into their fresh, young faces. Awkward but charming, they don’t miss a beat, explaining their fascination with Wainwright’s music started with his 1998 eponymous debut and was sealed upon hearing 2001’s Poses. “Sorry to give such a half-assed interview,” quips one boy, looking away from the camera and down at his feet. “It’s our first interview,” comically ventures the other.

“What brought me out? The chance to see God, basically,” breathes a middle-aged woman at the very front of the line. “How often do you get the chance to see God?” Overweight, plainly dressed, and wearing no make-up, she looks as if she hasn’t smiled since high school; exactly the sort of someone you might expect to wait for hours and hours in a place like this. I would feel sad for her, and ashamed of my condescension, if she wasn’t so starry-eyed. The opportunity to meet her hero has activated something beautiful in her; something poignant, wonderful, and better than Botox.

Idolatry is an eerie phenomenon. We identify with an artist who touches us, who, we are certain, understands our pain and personifies our isolation, who lives a secret life just as lonely as our own. His success becomes our validation: if he is loved, then we could be, too. And more so than other pop stars, Rufus Wainwright speaks to the outcast in us all. (Remember, even prom queens have dark sides.)

Why? The answer is simple: Wainwright makes no attempt to hide his vulnerability, perhaps recognizing that beauty lies in imperfection; in crooked lines, failure, misplaced emotion, and the divinely impossible process of trying to figure it all out. Both artistically and personally, he isn’t afraid to show his bumps and warts, as my acting coach would say, those beautifully hideous coming-of-age elephants in the room that white-bread propriety would have us ignore. For instance, it’s no secret that Wainwright has been openly gay since his teens, nor that the songs on Want One are the result of his turning thirty, burning out on rock ‘n’ roll living, and going through drug rehab. Expertly warbling and wavering, he sings about aching for romantic love, hot one-night stands, parental indifference, and the uneasy comfort offered by chemical vices. When I later inquire about the tiny gold flip-flop pendant dangling from his neck, he will happily explain that his “naturally smelly feet” function well in open-air footwear. “If I don’t air them out they’re weapons of mass destruction,” he says.

Most telling of all, this highly idiosyncratic artist has managed to succeed by being himself, thus accumulating credibility points like frequent flier miles along the way. How great it must feel, how honest, to be admired for doing your own thing, however weird; for respecting your calling, however a long shot; for being yourself, however larger than life. It’s what’s supposed to happen, our parents told us, when you work hard and stay true, their simple words mirroring the comfortably predictable reward and punishment system of religion, politics and fairy tales.

Neither the fairy-talesque romanticism nor the humour inherent in the dramatic arc of his own inner life have been lost on Wainwright, whose album art draws from lavish theatrical imagery. “The cover of Want One is me dressed as a knight in shining armor, the ‘triumphant hero,’” he will say. “The cover of Want Two is me as Sleeping Beauty, representing the feminine side of my nature and the world. It’s a little more sensitive, just me in a dress. It looks great! I’m a big fan of the golden age of Hollywood, of opera. In that way, fashion and art have been crucial in my development.”

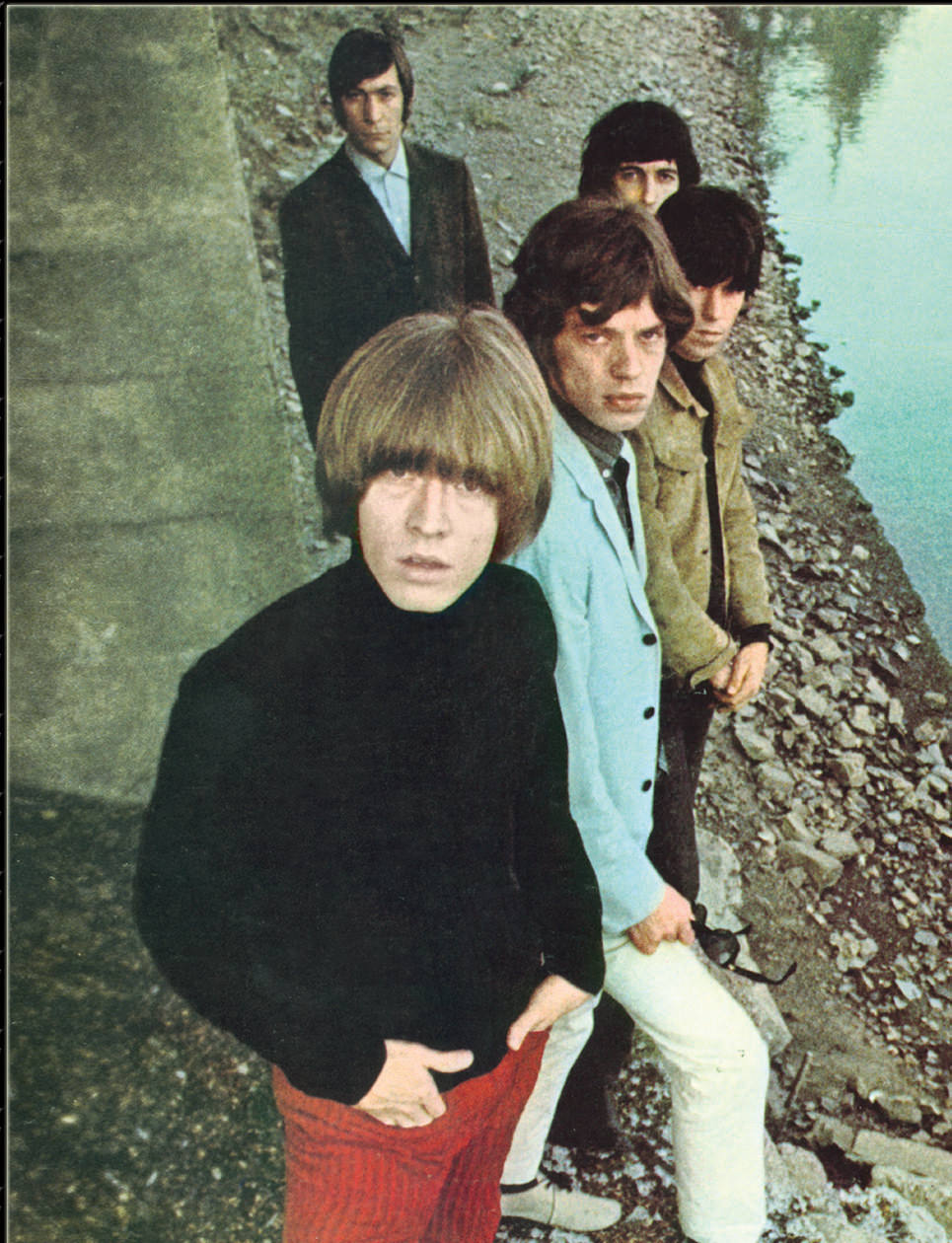

Even for a guy in a dress, putting it all out there takes a certain heftiness of balls. Especially when it sometimes seems like 99 percent of the world doesn’t get it. No wonder outcasts adore him. Not to imply that Wainwright appeals exclusively to wallflowers. On the contrary, Wainwright is really, really cool. His admirers include Sir Elton John, R.E.M.’s Michael Stipe, and Sting, with whom he toured Europe last summer. His cheery, well-dressed mug routinely appears in New York’s gossip pages, photographed at all the right parties wearing jaunty hats and canoodling with hip generational luminaries like Sean Lennon and longtime friend Melissa Auf Der Maur. The former Hole and Smashing Pumpkins bassist, also from Montreal, has publicly admitted that Wainwright was her first crush.

Downstairs, the door finally opens. Surrounded by a mini-entourage of management and label people, in he sweeps, or maybe he saunters, exuding friendliness, poise, and a lovely ruffle of self-mockery.

“Should we stand next to the punk rock? Pop? Or heavy metal,” I wonder out loud, trying to select a suitable corner of the basement for our chat. He grins. Rufus Wainwright is very tall, much taller than I, so he instinctively bends at the knee and spreads his legs into a sort of straddling position, thus lowering his torso so we share the same eye level. He is just as generous with his words, taking the trouble to really talk, rather than spewing forth premeditated slop.

“I honestly believe the whole world revolves around me,” he chuckles, when I ask about the relationship between his personal life and the planet. “It might be megalomania but my feelings are tied to world events, to that collective subconscious. As a musician, I try to tap into that fog and make sense of it, to find a way to personalize it. The first Want record was about my personal battles and triumphs over darkness. I looked around and realized the rest of the world is in a somber place. Want Two is very different. It’s a darker record, but also warmer. I felt free to express the full range of my dramatic impulses. I did feel shackled with the first two records. More experience means the ability to express myself more succinctly.”

Aided by producer Marius DeVries (renowned for his work with Bjork, Madonna, and David Bowie), both Want installments showcase Wainwright at his uncensored peak. Family is a major theme, with sister Martha contributing backing vocals, mother Kate on banjo, and aunt Anna on accordion. “Dinner at Eight” is about his formerly estranged father, musician Loudon Wainwright III. At a literal level, the piece describes the fight that led to his father leaving, but as Wainwright explains, it’s really a love song. “I’m afraid of my father like all sons are. Our relationship is one of intense love, intense fear, intense respect and intense disrespect. A lot of the keys to my psyche and my well being lie in that relationship. The issues that result from not having a father around, or the son rebelling against the father, are universal.”

Wainwright is also inspired as a songwriter by the same mythical archetypes that turn him on aesthetically. For instance, based on the Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, “Memphis Skyline” is a tribute to the late Jeff Buckley, the influential American songwriter and guitarist who in 1997 drowned in the Mississippi at the age of 28. “It’s a prayer for peace—one of my masterpieces,” he says. “I’m Orpheus, descending into the Mississippi to try to revive him. It’s a very dramatic piece about one living songwriter singing to a songwriter who’s dead. We’re getting back to that romantic weepy Rufus era.”

Yet behind his likeable playfulness, Wainwright at times seems wistful for things not yet happened. This premature nostalgia gives his music an otherworldly timelessness that renders indistinguishable any difference between the banal and the grand; the everyday and the epic.

And as art imitates life imitating art, Wainwright is now delving into the film world. He recorded a duet with Dido for Bridget Jones: The Edge of Reason, “I Eat Dinner,” a song originally recorded by Wainwright’s mom. As well, he appears in Martin Scorsese’s The Aviator and in the forthcoming Merchant Ivory film, Heights, which was shot in New York City.

Interview over, Wainwright heads upstairs to meet his followers. He sits behind a folding table and receives them one at a time. First up is the middle-aged woman with stars in her eyes. “Hiiiiiiiiii, bonjour,” he croons, a sincere smile frozen on his lips. Her voice a whisper, she hurriedly asks him to autograph a portrait of himself. He signs his name with a flourish. “God bless you,” she says, before dissolving into the crowd.