-

Artisan at work in the design studio at Harry Winston.

-

Ronald Winston.

-

Emerald and diamond necklace designed by Ambaji Shinde. Pendant is 104.40 carats.

-

Ronald Winston holding both the Hope (blue) and Dresden (green) diamonds.

-

Cushion-shaped solitaire with two baguettes (20.70 carats).

-

Mr. Harry Winston.

-

Ambaji Shinde at his design table.

-

Mr. Shinde adding the grace notes to a pendant design.

-

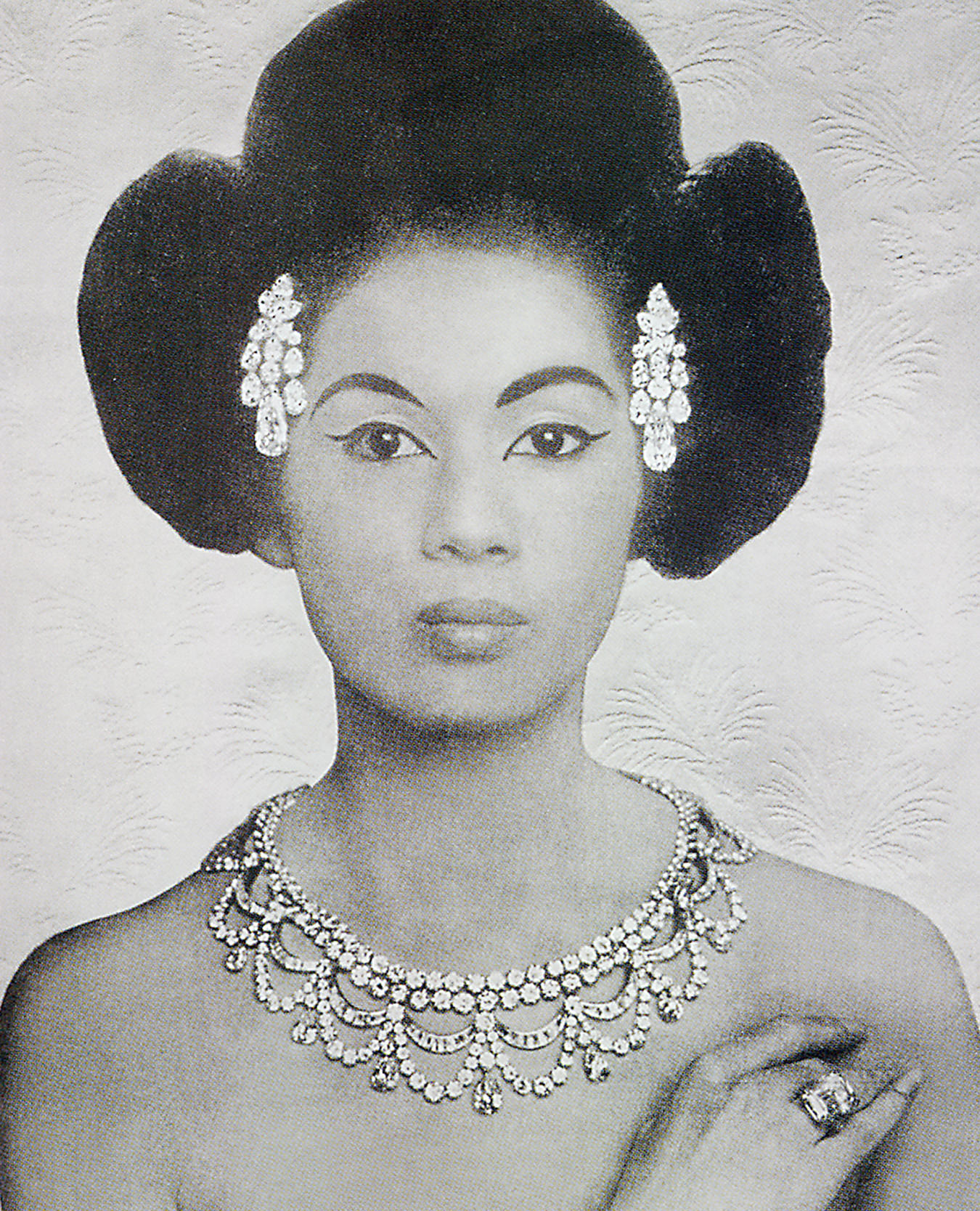

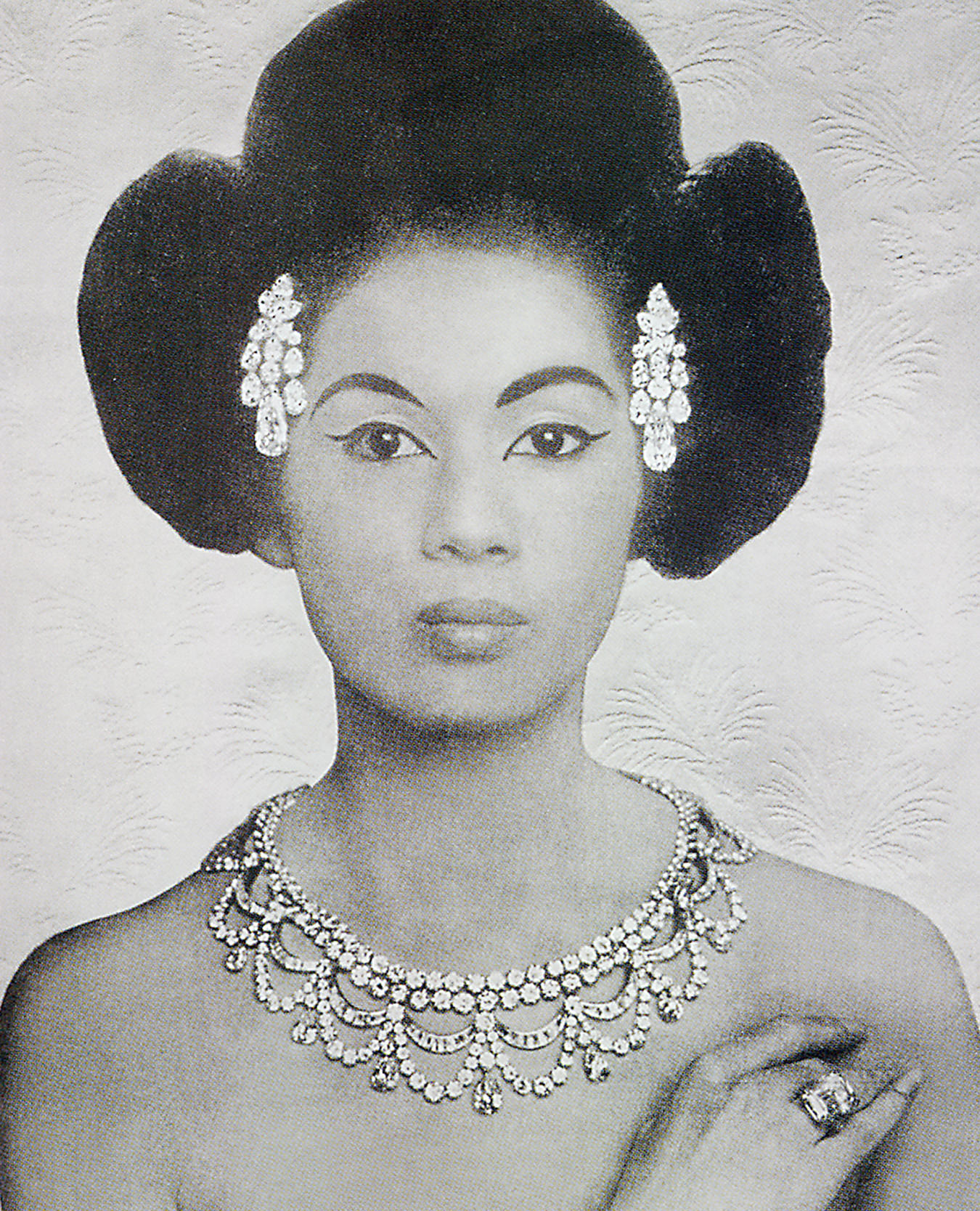

Advertising campaign from the 1940s; Anticipating Asia.

-

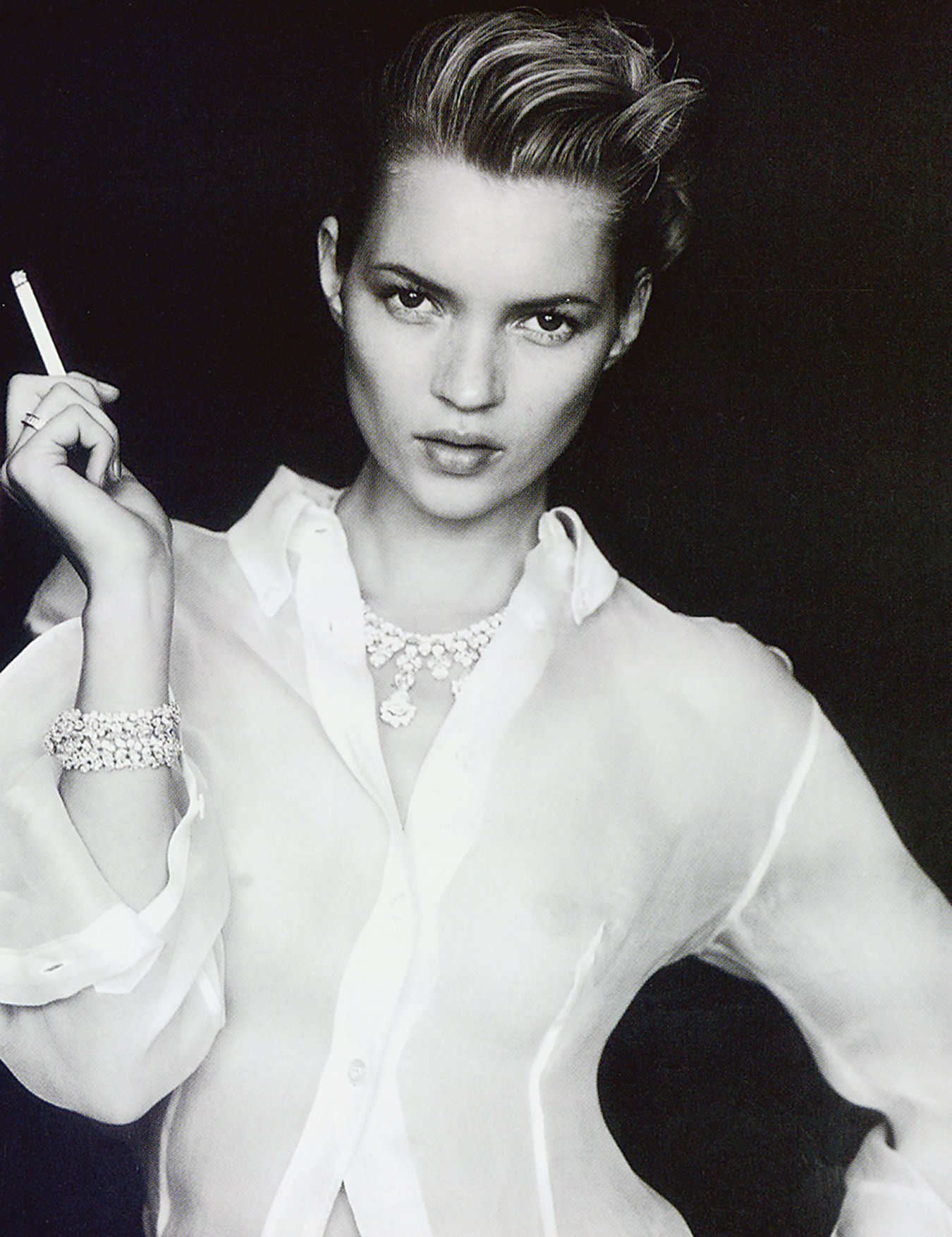

Advertising campaign from the early 1990s; Red chic and rubies.

-

Kate Moss, the ’90s It-girl.

-

Brooch of cushion-cut yellow diamonds (54 carats) with pear-shaped diamond (42 carats); diamond cuff bracelet (51 carats); two rings, yellow diamonds and triangular whites (23 and 31 carats).

The Legacy of Harry Winston

Black carbon, bright fire.

Artisan at work in the design studio at Harry Winston.

The American Avenue. From the French avenir, to proceed or to go, referring not to the act but that which facilitates the act. Paving likely but not strictly requisite, most certainly not to be confused with a promenade or alley. Names reflect and accrue historical import; Madison, Park, Columbus. But the most famous of them is also the most benign signifier.

This is Fifth Avenue, New York City, where a master designer overlooks the crush of noontime pedestrian traffic at the intersection partnered by that Latinate derivative, street (53rd, that is), where a fireman and a banker sit at dark mahogany tables, each establishing what they wish to purchase, they only knowing for whom. This is where the Harry Winston shop holds discreet sway as it has since 1947, and where the unphotographed but intensely real, and intensely articulate, Ronald Winston plies his many talents.

Ronald Winston.

Ronald is the third-generation Winston to oversee and guide this enterprise. He has done so since his father’s death, in 1978, and the renovations reflect in an important way the ease with which he handles the pressures incumbent upon him. The house of Winston has, from Harry’s time onward, been about the stones, and it is easy to grasp this while grasping for a brief and shining moment some of the unworldly beautiful stones they have designed, cut, polished and set under Ronald’s aegis.

Enter the vestibule, recently renovated but only to reinforce the understated elegance of the entire building, and await your consultation. There are more formal rooms to the back, where actual gems and settings can be examined. There is a special charm, related to a culture that knows no bounds where public displays of taste, influence and affluence are concerned, that Harry Winston knew very well, as the “Jeweller to the Stars”. The house still adorns many on Oscar night. Here in your hand might be the ruby and diamond earrings Sigourney sported two years ago, or the choker Gwyneth garnished when she won Best Actress. (Actually, its identical twin; Gwyneth’s parents purchased the original the day after the awards.)

Emerald and diamond necklace designed by Ambaji Shinde. Pendant is 104.40 carats.

Carrie Niese, Associate Manager of Communications, explains her choice of pieces as she presents them: “Colours are in at the moment. It’s likely because they carry a personal touch, a unique element that cannot be copied.” Intense brilliant 27-carat earrings; a chocolate diamond necklace showcasing a brown-yellow gem with many small brilliant yellows; the vivid orange “Pumpkin Diamond”, 5.5 carats and astonishingly bright, bursting with the internal fire that epitomizes the unique attraction of diamonds. To allow it temporarily to adorn even your pinky finger is to partake, however modestly, in history. The earrings, bracelets, and necklaces are all extremely malleable as well, comfortable to wear. (There are rumours that Madonna, in the heat of a dancing moment, lost 25 or so carats of earring one evening, but an intrepid chaperone recovered the gem.)

The artisans who construct these pieces work at stations where no space is wasted. Gem settings are handmade, placed in a wax base, or layout, to maintain shape as each individual component is made. Platinum wire settings ensure the focus is on the gem, something Harry Winston instituted, something of a break with tradition. The stones themselves are cut at a carbon wheel covered with diamond dust. Ruvin Menendez is on the wheel, and explains that the diamond dust is necessary because that thick 500-rpm wheel will be cut apart by a tiny diamond if applied without the layer of dust “You need a diamond to cut and polish a diamond.” He says the wheel can accommodate anything from 2-point to 60 carats. Has he cut a 60-carat stone? Yes. Was he nervous? He laughingly says, “someone has to do the job. But it is a very slow process, because if you cut too much, you can’t put it back.” Calipers and a hyper-sensitive scale tell him when his job is perfectly done, and he performs his tasks with the concentration and delicacy of a surgeon.

The house still adorns many on Oscar night. Here in your hand might be the ruby and diamond earrings Sigourney sported two years ago, or the choker Gwyneth garnished when she won Best Actress.

These talented people all rely on the work of 84-year-old Ambaji Shinde, master designer for Harry Winston since 1965, and designer to the Indian Royal Family for two decades before that. Harry, ever an acolyte for diamonds and design, convinced him to move, first to Geneva then to New York, in pursuit of perfecting his craft, and with access to many of the largest, finest gems in the world. A fine marriage; the adjustments to Western life were inconsequential to him. “No problem whatsoever. I enjoyed myself very much. I have had a wonderful life, doing what I am good at, what I like most of all.” Ronald Winston says Mr. Shinde is a unique talent, an artist in his own right, who can provide renderings of settings virtually on the spot. “Even the most prized designers usually need 24 hours to come back with something. Ambaji can do it right in front of the client, while we wait. And he can provide alternatives, discuss the logistics, the price. Amazing.”

The wall behind Ambaji’s draft table is fully lined with binders bursting with his designs, all meticulously labelled. Open any one, and you can see the minute thematic variations on necklaces, rings, earrings, all in colour, all perfect in their own way. These constitute the bulk of his work, the sweaty genius of it. “This is the way I do it,” he says. “I have an interview, focusing on the beauty, the best we can do; then, after I hear their desires, such matters as price. The size, difficulty in obtaining eighteen stones that will look exactly alike, for an example, and what the client would exactly like are all discussed. I then put it on paper. Simple.” He is a modest, soft-spoken person. The dollar figures and the rarity of gems he has handled and designed settings for do not in any way faze him. There are pieces worth millions of dollars that interest him less now, as they did upon execution, than several that are within any budget. It is all about art, creating the ideal setting for a particular jewel or series of jewels.

Ronald Winston holding both the Hope (blue) and Dresden (green) diamonds.

His renderings are art works in themselves, meticulous, detailed, evocative, beautiful. Many of them are already bequeathed to the Smithsonian Institute for posterity. He knows what the piece will look like in its final form: “Oh, yes, indeed. I can picture it very clearly, and if there is something that will not work, or requires stones that are too difficult to obtain, I explain that as well. Sometimes, for a special piece, the client must wait many months, until just the right stones become available.” He smiles knowingly: “This is when things become expensive, when you need a specific stone or set of stones to make the design.” He is the person who designed the Taylor-Burton pendant with which Elizabeth Taylor displayed her legendary stone, a 69.42 carat pear-shaped diamond. The original rough 242 carat gem was cut by Harry Winston. The stone was purchased at auction in 1969, and sold the next day to Richard Burton, who made of it the most famous, and expensive, diamond gift up to that time. (Taylor later sold it at auction to help build a hospital in Botswana; the diamond itself has not been seen since 1979, when it was purchased for $3 million.)

For Shinde, “it has been a wonderful occupation. I have met so many people, and I have so many stories to tell.” As he prepares for retirement, finally, he is that serene individual who clearly has no regrets.

Portraits of Harry Winston embody a cherubic, outgoing man who was confident in his work. He was a showman with a detailed, prescient eye for quality stones in rough, an ability that cannot be learned, which he translated into splendid business success. The connection to Hollywood prestige was a small part of the true glamour of the house, which still provides pieces to sultans and kings, presidents, and maharajahs. Harry’s father founded the company in 1890. A watchmaker and jeweller, he established quality criteria that Harry concentrated on rare gems, most particularly diamonds. He was idiosyncratic, often sending rare gems, such as the “Jonker” (at 726 carats, the seventh largest rough diamond ever) through registered US mail. Harry Winston had relationships with key industry figures, such as the philanthropically minded Harry Oppenheimer, who provided Winston access to special stones, rare for size, clarity, and brilliance. The “Deal Sweetener” came into his possession at the conclusion of the largest single diamond transaction in history, in which Winston purchased a parcel of rough diamonds from Harry Oppenheimer for nearly $25 million USD. When asked to add “a little something extra,” Oppenheimer produced a 181 carat rough from his pocket and rolled it across the table.

While stories such as these may seem to constitute the entirety of the diamond and design business, they are in truth fascinating exceptions. Sourcing stones, evaluating them, creating designs either to order or speculatively, is the meat and bones of a successful business. Ronald Winston assumed control at Harry’s passing, and has embellished the house’s reputation while bringing it full circle with the reintroduction of timepieces. But he has rigorously maintained the lustre through painstaking detail, overseeing every facet of the operation and reserving final approval on every design, from conception to finish.

His renderings are art works in themselves, meticulous, detailed, evocative, beautiful. Many of them are already bequeathed to the Smithsonian Institute for posterity.

Ronald Winston is a distinguished, casually elegant person, who spends little time in what would be described in pulp fiction as a “cluttered” office that bears strong resemblance to an Edwardian den. The chairs are deep, wide and accommodating, bookshelves are bursting, framed pictures adorn walls and floor space alike. He is thoughtful and articulate, with a clear sense of his place in a business with so many relationships to artifacts that embody history. “My favourite part of all is seeing the finished piece. It’s all about the stones, and to see everything come together is always special.” Ronald has spent time “in a pitched tent, in a jungle somewhere, waiting for stones.” So he knows the entire process well, and respects both the stones wrought from the earth and the hands that claimed them. “We spend much time in the studio ensuring that metal does not show in our pieces. We build monuments, not decorations.”

Mr. Harry Winston.

He is the self-described “creative spirit and corporate director” of Harry Winston. There are no joint ventures, so the company has direct relationships at all levels of the industry, from those tents to certain luxe hotels in Saudi Arabia, from Paris to Osaka. On occasion, Ronald may personally deliver a special piece to a distant client, though less frequently now than ever. (Still, for insurance purposes, no photograph of Ronald Winston exists.) He began by acquiring “an osmotic education” into the business, when his father brought gems home, or shared his love of the job. “I actually wanted to be a scientist, and I started an AIDS foundation back in the 70s. My father wasn’t ill, so his death was sudden, unexpected. Soon after that came the diamond market crash, which I predicted, but I still had to fight to get my job.” The company was, and is, a complex apparatus, and Ronald had to show his true aptitude for the work before “inheriting” the mantle. His degrees in chemistry and English literature have stood him well as he guides the company along. He has invented several studio tools and computer programs that assist in evaluating rough diamonds and in the exacting rigours of cutting.

And through it all, he approves each design. “Each design is not a blueprint, it is an interpretation,” he says. So when the time comes to make physical commitments, of time, and human effort, to cut, polish and set gems, there is always the intuitive accompanying the rational. “I sometimes play clean-up for our over-exuberant sales people. I was once asked to confirm in writing that a setting was ‘the finest emeralds in the universe’. Well, I wasn’t sure what to say right up to the moment I first spoke directly with the client. I said what I could put in writing was that these are the finest emeralds known today, but that God may well have the earth yield up something even better tomorrow morning.” He completed the sale.

Advertising campaign from the 1940s; Anticipating Asia.

Diamonds are a natural phenomenon, no different than coal, loam, granite, marble. To each its added value, that relies on scarcity and an arbitrarily defined “quality”. For gem-quality diamonds (there is a tremendous business in industrial diamonds as well), utility is completely beside the point, and when the Indian sub-continent first assigned value to these highly compressed portions of carbon, it was because they were shiny. Not so shiny as they are at the beginning of the 21st century, thanks to highly evolved cutting and polishing techniques, but even today a gem’s brilliance is its most important characteristic. Size dictates rarity, and prices are gauged accordingly, or perhaps disproportionately, depending on the purchaser.

Ask Ronald Winston if he believes, as many did in older times, in any transcendant quality in diamonds that might in some oblique way account for their high monetary value. “No, not in any transcendental value, no. However, I do recognize in diamonds and other precious gems a leitmotif, in which their presence in historical events somehow comes to represent the events and the people associated with a specific time.” He moves to a corner of his office, picks up a framed photograph, of his own hand and arm, crisp cuffs showing under a thin pinstripe suit sleeve, cradling in the palm both the Hope and the Dresden diamonds, the largest blue and the largest green of brilliant quality known to history.

The Hope was discovered in India nearly four centuries ago, purchased by Tavernier who in turn sold it to Louis XIV, in 1668. Called then the French Blue, it began to accrue its aura of tragedy, as one after another of its owners and wearers suffered unlikely and often ignominious fates, exemplified by Countess DuBarry, Louis’s mistress, who wore the diamond, but not on her date with the guillotine.

“My favourite part of it all is seeing the finished piece. It’s all about the stones, and to see everything come together is always special. Each design is not a blueprint, it is an interpretation.”

Henry Phillip Hope eventually came into possession, and his name stuck. So did the curse. Harry Winston purchased the stone, along with several other jewels, in 1949, and although he travelled with it frequently, the curse had no effect on him.

The green Dresden, as Ronald Winston can inform you in the manner of a tenured history professor on Oprah, began with its first appearance in London in 1726: “Augustus of Poland bought the stone, and used it in a badge of the Order of the Golden Fleece. (No one knows for sure, but when Louis XV set a blue gem in his own badge five years later, it was likely what we know now as the Hope.) The Dresden spent time in Russia after World War II, but is now safely back at home, in the Green Vault Museum.” Winston’s passion for his subject is obvious: “So much history, so many key events are associated with gems of this type, gems rare beyond belief. The gems are so rare, so beautiful, that powerful figures find them attractive, and they of course can at certain points have access to them. And the events that surround these figures then surround the gems. That is why I wanted to place the green and the blue together, for people to see. There is so much history attached to them, and they are so similar, in origin, size, intensity and historical importance.” Boron deposits make diamonds blue; natural radiation makes them green. Diamonds can be irradiated to make them green, but the Dresden is completely natural.

Jeffrey Post, curator of the National Gem and Mineral Collection at the Smithsonian Institute, where Ronald succeeded in uniting the Dresden with the Hope (which is permanently placed there, a gift from Harry Winston): “Part of the reason the Hope is so well known is that it’s large and blue. Green is even rarer than blue in diamonds and no other green diamond in the world is even close.” Ronald Winston wanted to unite the two, however briefly, to underline the reasons why gems take on such extreme value, benign partakers in the march of history, and not aligned to a specific narrative. From there it is easy to extrapolate the .75 carat engagement ring, the half-carat anniversary stone, or any gem however modest, as a repository of the significance of the events and people it pays silent testimony to.

Brooch of cushion-cut yellow diamonds (54 carats) with pear-shaped diamond (42 carats); diamond cuff bracelet (51 carats); two rings, yellow diamonds and triangular whites (23 and 31 carats).

The Manhattan afternoon rush, the ebb and flow of traffic pedestrians obviating signal lights, the neon reflections of American dreams at Times Square, the long lineup at Tickets, Tickets, (‘The Lion King’ and ‘Aida’ are long sold out for that day’s allotment), will clutch and grab you upon exiting the store. But as Ronald Winston continues his contemplation of rare gems and their meaning, all else can wait. “The Edwardian and Deco eras are not all that relevant today, in terms of actual design. Retro is still relevant, because of its relation to the concept of streamlining. Cartier and Tiffany, as designers, had different challenges. Brightness as the mark of quality is not as important now, partially because given the technology, it is possibly taken for granted.” There is about Ronald Winston the still water philosopher: it runs deep. His awareness of history, gemology, and aesthetics are inextricable from his sense of clients and the business which serves them. “I have a keen eye for colour in a diamond, and to find fancy-coloured gems of significant size is one of the true tests at the moment. I think these are sought after for size and rarity, certainly, but also because these kinds of gems draw attention to the time they are in, the people and events that surround them.” The fourth movement of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony, the first notes repeated regularly, often, to reaffirm an emotion, or perhaps, more accurately, a relationship to an emotion, the leitmotif, a Wagnerian flourish; in gems, a constant reminder of a signal note in a life, a remembrance, a harbinger. For Ronald Winston, a metaphor you can observe, touch, or even better, a metaphor you can wear. That is where we must leave it.

Take what you can gather from coincidence. Not far from Harry Winston, at the Museum of Modern Art, many of Giacometti’s works stand, for a limited time, in mute but eloquent tribute to both his talent and the objects of his eye. Or Daniel Boulud offers food of the Lyonnaise countryside at a little bistro close by. Intuition and enterprise, here on the avenue in New York, and everywhere else, too. Strike another match, start anew. Black carbon to bright light. History, like the value of a gem, is a construct. Deep. Well cut. Or not.