Andrea Bocelli

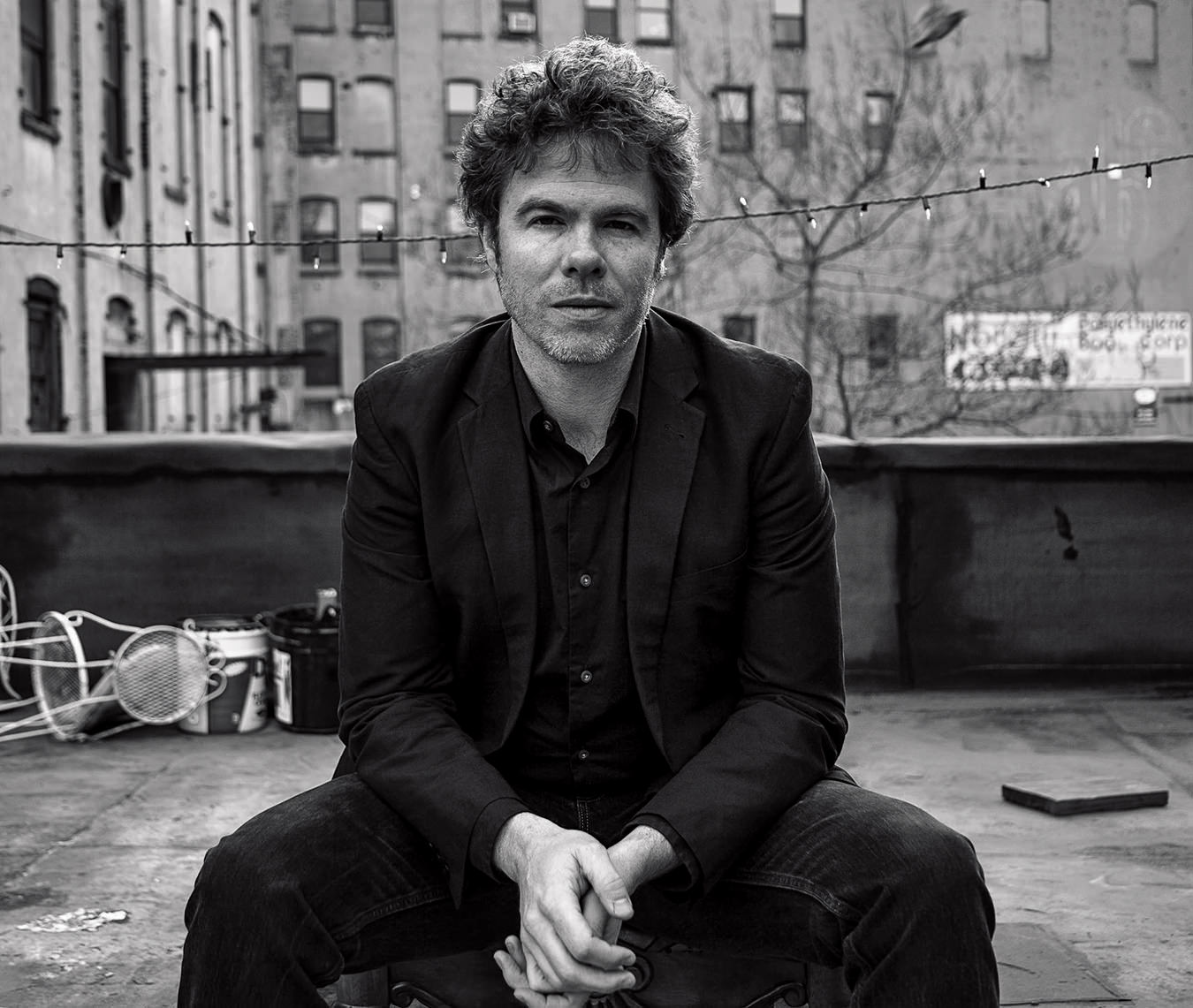

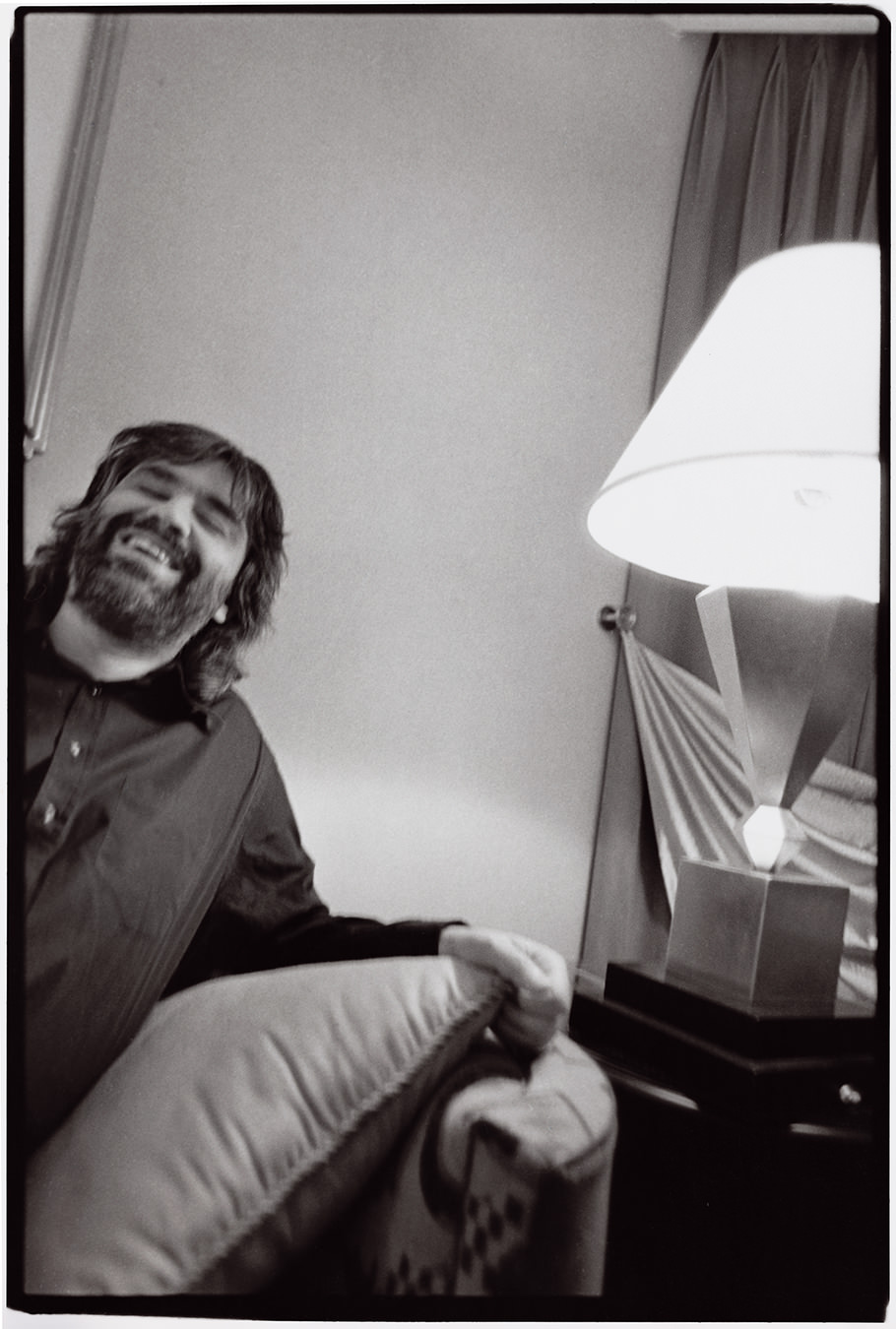

Bocelli in Manhattan.

The suite at the Righa Royal, a midtown Manhattan hotel, is elegant, but too small for the crowd milling around. It’s cocktail time, but there are no cocktails; tenor Andrea Bocelli, whose temporary refuge this is, must protect his voice from the ravages of alcohol. Huge baskets of fruit and other treats, swathed in coloured cellophane, are positioned ornamentally throughout the room. Bocelli is tired. He’s running late. He’s been on display for the last three days, promoting his newly released CD of La Bohème. He’s been charming on PBS’s late-night Charlie Rose show, and tomorrow he has to be chipper on one of the national network morning programs. Bocelli’s flying trip to North America, in the waning days of the year 2000, has been devoted entirely to publicity, and it’s clear that he would rather be singing, or sleeping, or back on his farm in Tuscany with his wife, Enrica, and his two little boys. Around him swirl his manager, his Canadian publicist, his translator, his younger brother (a very tall person with a very long ponytail), a photographer trying to get a picture of a man rarely alone or still, and this notetaker. Most of the Italian party is dressed in black.

Waiting to speak to Bocelli, in the hall outside his room, we’ve listened through the door to him vocalizing. Once we’re inside, settled in chairs, the big, shaggy singer speaks quietly; his pretty translator absorbs great swatches of his talk and fires them back at me.

Although he’s been a phenomenon in Europe since the mid-1990s, when he toured the continent with Italian rock star Zucchero, Bocelli’s discovery in North America dates from his appearance on a PBS special in late 1997, when he teamed with Sarah Brightman at the World Cup to sing “Time to Say Goodbye.” Celine Dion said “If God had a voice, this is how it would sound.”

I’m fascinated by his reputation, by the factoids that come at me whenever I mention his name. A friend in arts management tells me Bocelli’s voice was broadcast by the city of Providence, Rhode Island, booming out along a new downtown walk beside the Providence River. “Providence,” my friend explains, “is the sister city to Florence.” Thus, it seemed appropriate to have the riverwalk christened by Bocelli’s “Italian art song voice.”

Critics of classical music have been cynical about Bocelli, but a world-class music writer of my acquaintance declares “As a singer of romantic, quasi-operatic Italian pop, he’s just fabulous.” Another critic revised his opinion after hearing Bocelli’s Boheme. “As long as you accept the fact that this is a microphone voice and by nature never intended for experiencing without amplification, Bocelli really does live up to the hype,” enthused Allan Ulrich in The San Francisco Examiner. “This Rodolfo simply sounds young…unusually intimate and sensitive [and] endowed with the soul of a poet.”

“If God had a voice,” said Celine Dion, “this is how it would sound.”

A year ago, Bocelli performed for the Pope. His recordings dominate Billboard’s classical music charts, and top ticket price for his one Canadian concert this year (April 6 at Toronto’s Air Canada Centre) is $550, more than Pavarotti commands. He has founded the Premio Bocelli, a biennial contest inviting listeners to write songs for him. If you type his name into Google, you will find upwards of 43,000 files (and growing) including a highly sophisticated website maintained by the 42-year-old tenor’s worldwide fan base. If you go to bed early, the site will give you the full text of his late-night television interviews. If you sleep late, log on to read transcripts of his morning show gigs from several countries. There are video and audio, links to shops ready to sell you CDs, poems written to him in several languages, and pages of photos of the countryside around his birthplace, the Tuscan town of Lajatico.

How did he get from that farm community to international superstar status? “It’s really just how life went,” he says. “The greatest soccer players in the world are discovered playing with naked feet in the back yard.”

Well, it’s maybe a little more complicated than that. An ordinary kid with an extraordinary voice—the kid made to sing for relatives at every opportunity—lost his sight after a soccer accident when he was twelve. But he went on to law school and, to earn his tuition, found a gig in a Pisa piano bar. His primary inspiration was Franco Corelli. Although, he says, “I loved many, many voices, for years I got drunk on Corelli’s style, but there came a point where I had to depart and find my own style.”

“A voice, singing, can be a ray of light on a grey day. I really believe that.”

How does he prepare for a role? “I listen to a recording. I study the part with a pianist, try to enlarge my repertoire. On stage, there is a director. He teaches us everything.” Bocelli is determined to succeed on opera house stages. “Opera was born and grew up in theatres, and it will remain in theatres. If it were to die in the theatre, it would also die on CD and television.

“That is not to say it shouldn’t be on CD, and especially on TV. A lot of people, myself included, found their passion for opera through CDs and mass media. Even today, I prefer to listen to an opera on CD than going myself to the theatre. I can stop it, repeat a particular piece three or four times, skip some parts I don’t like.”

The singer’s North American popularity has been further increased by the playing of his voice on The Sopranos. He had not been aware that he is a factor in the phenomenal success of this HBO (CTV in Canada) series on mob life, but the idea amuses him. It reminds him of what Gianni Agnelli, CEO of Fiat, is reputed to have said when a powerful mafioso acknowledged respect for him: “Go tell Mr. Tommaso Buschetta that his trust is well placed.”

The success of Andrea Bocelli is particularly striking at a time when, one critic says, “The classical music business is in crisis. A top opera recording is not likely to recoup its investment. Companies go in for crossover; it’s good for the bottom line.” Bocelli, he says, is only the most recent in a line of crossover stars, including Mario Lanza, Sergio Franchi and, of course, Enrico Caruso, “the first million-seller in record history. There had always been the sense that a big Italian tenor could exist outside opera. Pavarotti paved the way.”

Bocelli takes his gigantic popularity in stride. “I’m very happy about this, happy to be for my audience what the great singers of the century have been for me when I began my journey. A voice, singing, can be a ray of light on a grey day. I really believe that.”