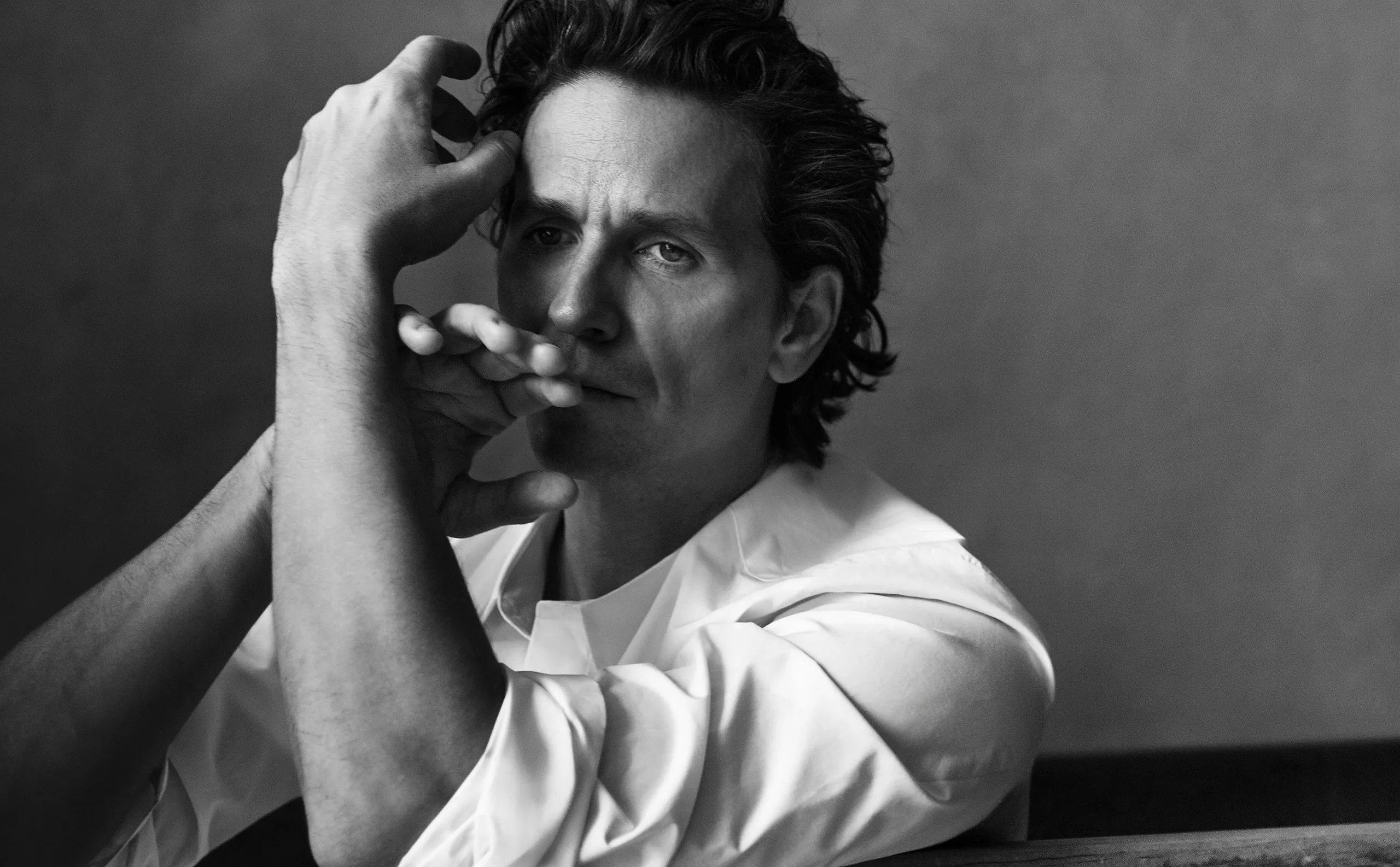

Guillaume Côté: The Dancer Who Can’t Stand Still

For 43-year-old Guillaume Côté, set to take his final bow as principal dancer with The National Ballet of Canada, dancing is not just an identity but a way of being.

The morning after the late-March world premiere of Don’t Go Home at New York City Center, Guillaume Côté is in an apartment hotel in Times Square, visibly tired but animated as he reflects on the night before. Co-created with Canadian playwright Jonathon Young for New York City Ballet star Sara Mearns, the text-based dance piece marked a daring break from classical ballet traditions. For Mearns, the evening was a milestone: her curatorial debut as part of City Center’s Artists at the Center program. For Côté, it was a chance to challenge audience expectations of what ballet can be. “We wrote it with humour,” he says of the work, “but after rehearsing it so often, you don’t think it’s funny anymore. Sitting in the audience and hearing people laugh was refreshing.” Still, he jokes, “The New York Times is probably going to kill me.”

Not quite—the paper reviewed the program as ambitious and inventive, while another publication praised Don’t Go Home for its noir-like atmosphere and its ability to blur the line between dance and theatre. Mission accomplished. “I like shaking things up,” Côté says. “It’s about fusing classical ballet with other elements—new styles, new disciplines—to give it a future.”

This spirit of reinvention has defined Côté’s 27 years with The National Ballet of Canada, where he has served as both a leading company dancer and choreographic associate. This season, his remarkable career will be celebrated when he takes his final bow at Toronto’s Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts during Adieu: A Celebration of Guillaume Côté May 30 to June 5. “It is sad in a way,” he says, “but it’s also a new beginning. I’ve an epic work in me yet. I will share in due time.”

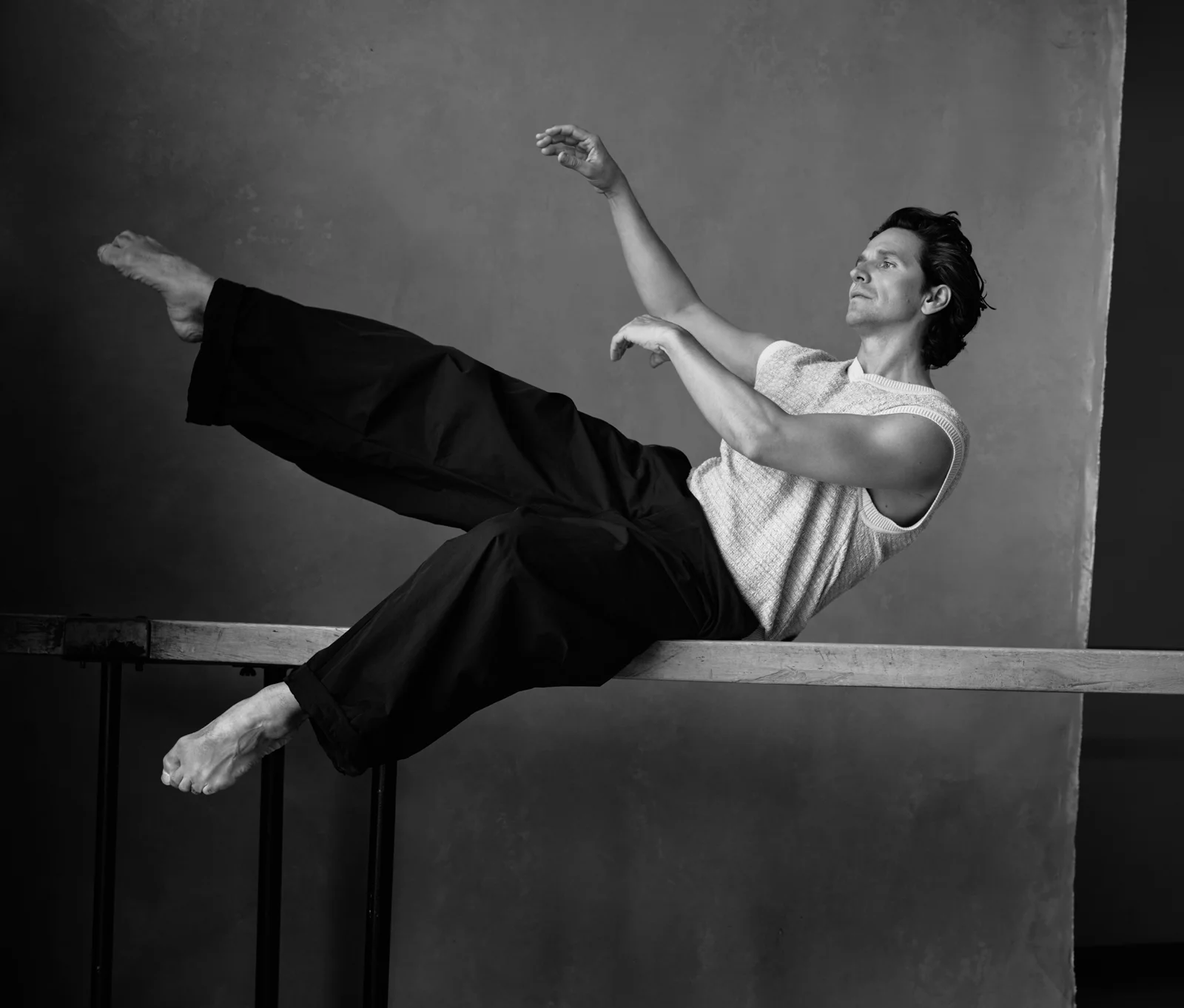

Guillaume Côté wears Boss.

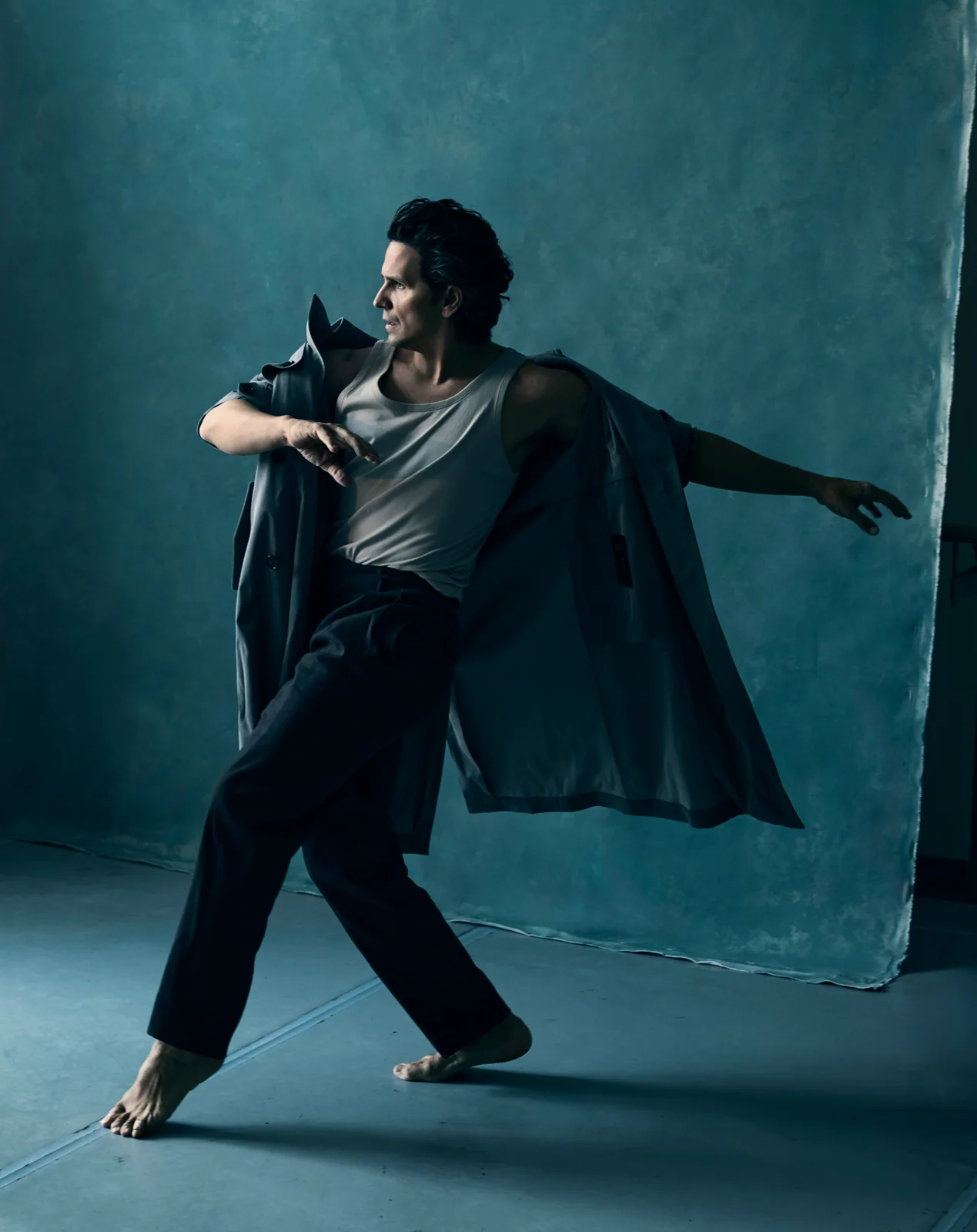

Over nearly three decades, Côté has shaped a career that defies easy categorization. Onstage, his movements are precise but never mechanical, infused with a fluidity that feels deeply personal. His striking features—dark hair, sharp jawline, hypnotic eyes—might suggest leading man, but his performances reveal something far more dynamic: an ability to dissolve the boundary between performer and audience. Beyond his technical brilliance lies a creative daring that pushes ballet into uncharted territory.

As a choreographer, Côté has sought to redefine classical dance through bold experimentation, integrating elements beyond movement alone. His creations include the Sartre-inspired Being and Nothingness and the multimedia-rich Frame by Frame, developed with the Quebec theatre maestro Robert Lepage. In 2019, he founded Côté Danse as a platform for independent work, producing acclaimed pieces like the immersive Touch and a reimagined Hamlet currently touring the United States. “We’re always interested in what Côté has to say onstage,” a New York critic recently remarked. “His imagination and skills cover several disciplines, and his artistic endeavours often have a visionary leaning that holds the viewer’s attention.”

Côté’s boundary-pushing approach to ballet will take centre stage in Adieu, where he will not only bid farewell as a company dancer but also debut new choreography and revisit select pieces from his body of work. Among the highlights is the premiere of Grand Mirage, a multidisciplinary solo performance created with filmmaker Ben Shirinian. Côté describes the piece as a metaphor for the elusive nature of artistic fulfilment—an introspective journey that reveals the mirage of an ever-unattainable goal. The program also includes the reprise of his 2012 Boléro, a contemporary reimagining of Ravel’s eponymous score that transforms its hypnotic rhythms into a study of power and vulnerability.

Complementing Côté’s works are new creations by Ethan Colangelo and Jennifer Archibald, two choreographers whose distinct approaches expand ballet’s expressive possibilities. Colangelo draws on classical foundations to craft intricate, emotionally charged movement, while Archibald blends elements of hip-hop and contemporary dance to create bold, kinetic works. Together, these pieces celebrate Côté’s artistic evolution and highlight the innovative spirit shaping the future of classical dance.

Guillaume Côté wears Boss.

“Guillaume thrives on collaboration,” says Anisa Tejpar, who has worked as a rehearsal director for his choreography. “He listens deeply—to music, to movement, to people.” A dance artist in her own right, Tejpar first met Côté in childhood at Canada’s National Ballet School. She knew Toronto, but he did not, having just arrived from Lac-Saint-Jean in northern Quebec. For Côté, the NBS was more than a geographical shift—it was a cultural leap. The son of proud Québécois parents involved in the separatist movement, Côté spoke no English when he first arrived. “It was tough—moving to the English side of Canada and being so far from home,” he says.

Tejpar remembers being tasked to help him adjust: “At 12 years old, being paired with a boy wasn’t the most riveting thing,” she says with a laugh. “But I was his first friend at the ballet school. I showed him where the ESL class was, answered his questions about words, and within six months he was speaking perfect English.” Decades later, as his trusted artistic partner, Tejpar jokes she remains “the best Guillaume Côté translator of all time—not just because I originally translated for him but because I know his energy, his taste, and what he needs.”

Those needs are rooted in ballet.

The art form became central to his life early in childhood, after his parents invited a dance teacher—France Proulx—to teach classical ballet to his sister and other kids in a local church basement. Côté started lessons when he was four, and it quickly evolved into an all-consuming passion.

___

“I had a videotape with all the greatest male ballet dancers—six hours of two-minute variations that I watched over and over,” he recalls, citing Mikhail Baryshnikov and Jorge Donn as early influences. “I was obsessed with ballet for a very long time.”

That devotion sustained him through moments of doubt and rebellion during his teenage years, when he fronted a rock band called The Neurotics, balancing nights playing electric guitar and singing at venues such as Toronto’s legendary El Mocambo with long days at the barre. “I wanted to be a rock star,” he says with a laugh. But while music remained an important creative outlet—he continues to compose ballet scores today—it was the physicality and storytelling of full-length ballets that ultimately drew him deeper into dance, driving him to excel and seek opportunities beyond Canada’s borders.

After graduating from the NBS in 1998, Côté enrolled at the School of American Ballet in New York City, where he built relationships with classmates who would go on to shape the dance world—including Jonathan Stafford, now co-director of New York City Ballet. But fate intervened during a tour by The National Ballet of Canada at New York City Center. Watching an all-Canadian program, Côté was struck by the artistry of his former classmates. “I thought, ‘I should be back in Canada.’”

Guilllaume Côté wears Boss top; Amomento pants available at Lost & Found, Toronto.

When he returned to Toronto at 17, he found himself at a crossroads. He could no longer stay with the family that had been hosting him, and he was unsure about staying with The National Ballet of Canada. That’s when Vanessa Harwood, a former principal ballerina with the company, offered him stability during a pivotal moment in his career. “He arrived on Halloween night, fresh from New York,” Harwood recalls. “He had nail polish on from a party and didn’t even know where we lived—he had to call [then company ballet master] Lindsay Fischer for our address.” Harwood and her husband, surgeon Hugh Scully, took him in as he began his apprenticeship with the company, solidifying his path.

Côté’s talent was impossible to ignore when he joined the company in 1999 as a member of the corps de ballet. His strong, fluid dancing style and innate dramatic abilities quickly caught the attention of James Kudelka, then artistic director and one of Canada’s most celebrated choreographers. Kudelka began creating ballets with Côté in mind, recognizing his potential to bring complex characters to life. Among the first was The Contract, a brooding work inspired by Robert Browning’s poem “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” In the controversial 2002 production, Côté played Will, one of the enigmatic leads, commanding the stage with an electrifying presence and leaving a lasting impression.

Building on that early experience, Côté’s meteoric rise in Canada’s largest classical dance company cemented his reputation as a star performer. Within two years, he became its youngest-ever Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake at just 19.

___

“Guillaume Côté became Mr. National Ballet of Canada—‘The Prince’—and such an up-and-comer so quickly.” says Anisa Tejpar, who remembers observing her former classmate’s rapid ascent.

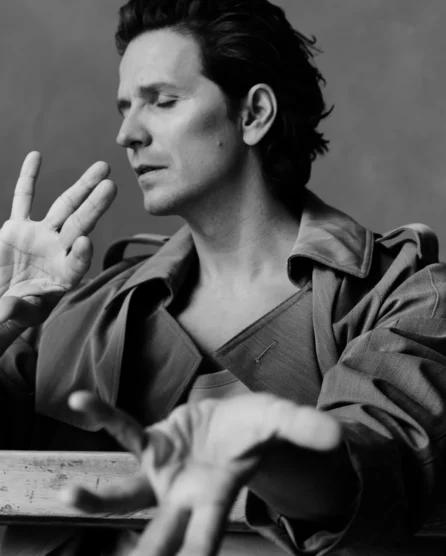

Today, his repertoire spans more than 75 ballets, including leading roles in Alexei Ratmansky’s Romeo and Juliet, Jiří Kylián’s Petite Mort, John Cranko’s Onegin, Ronald Hynd’s The Merry Widow, and Rudolf Nureyev’s remake of The Sleeping Beauty by Marius Petipa. Yet Côté’s artistry isn’t just about technical mastery or versatility across different dance styles—it’s also about the relationships he builds with his partners, the trust he fosters, and the way he elevates their performances. “Partnership is something you learn,” he says. “It’s not just about lifting or supporting—it’s about listening, adapting, and creating something greater than yourself.”

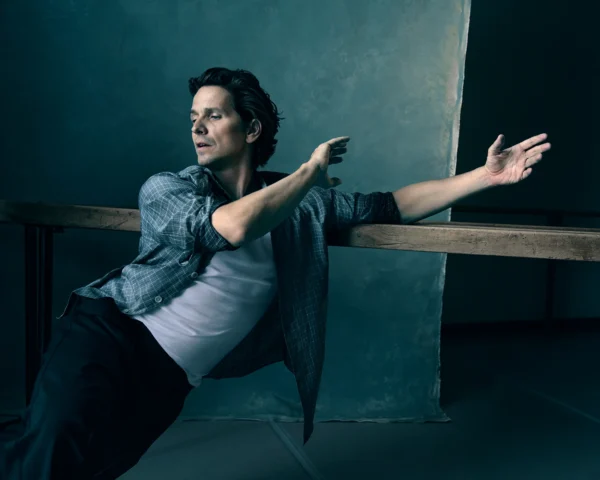

Guillaume Côté wears Amomento shirt available at Lost & Found, Toronto.

Over the years, Côté has danced alongside some of The National Ballet’s most celebrated ballerinas, including Sonia Rodriguez and Jurgita Dronina. Each partnership brought their own dynamic to the stage, but his connection with Greta Hodgkinson stands out. A former National Ballet principal dancer and now its artist-in-residence, Hodgkinson continues to dance with Côté through his Côté Danse company. She will return to The National Ballet stage for Adieu, her first time back since retiring as principal dancer. “We’ve always had an intuitive understanding,” Hodgkinson says. “I like to think we bring out the best in each other.”

That same drive to foster connection and creativity has shaped Côté’s work beyond the stage. Since 2015, he has served as artistic director of Le Festival des Arts de Saint-Sauveur, a celebrated summer event in Quebec’s Laurentians. Under his leadership, the festival has attracted international ballet stars and Canadian contemporary innovators alike. Côté runs the festival with his long-time friend and fellow artist Etienne Lavigne. They first met when Côté joined The National Ballet. “As one of the few Québécois dancers there, I naturally took on the role of guide and support for him,” Lavigne, a former company soloist, recollects.

___

“Guillaume Côté is a deeply creative soul and a consummate artist—truly a Renaissance man—always searching for the next way to stretch his artistic muscles.” —Etienne Lavigne, former soloist for The National Ballet.

But even with his many successes, Côté has faced setbacks that tested his resolve. “I didn’t get the Erik Bruhn Prize I had hoped for,” he shares. “Certain roles didn’t come my way.” And more recently, he wasn’t chosen as artistic director of The National Ballet of Canada—a position he had long aspired to. Injuries also tested his resilience. “I was really at the top of my game—dancing in New York, at The Royal Ballet, and alongside illustrious dancers in Kings of the Dance—and it broke me,” he says of tearing his ACL during an opening night performance of The Nutcracker. “The reality is, you don’t come back the same.” Côté was 33 at the time, and it took years for him to recover physically and mentally. “I worked my whole life—you work your body to its limits—and then an injury changes everything.”

Guillaume Côté wears Boss tank top; Our Legacy plaid shirt available at Lost & Found, Toronto; Harry Rosen NN07 pants.

The pandemic brought another devastating blow. “It was fucking shit,” he says, his voice trembling with emotion. “You work your whole life for those moments on stage, and suddenly it’s over. Pirouettes in your living room? That’s not what it is about. Dance is connection—it’s about the people in the room.” The isolation cost him dearly. He sank into a depression that he says he’s only recently climbed out of. Therapy has helped him confront the mental toll of a career built on relentless ambition.

His personal life has suffered too. His decade-long marriage to his long-time dance partner and fellow National Ballet principal dancer Heather Ogden—with whom he shares two children—ended in divorce three years ago. “You share the best of everything on social media,” he admits. “But we all have things we deal with behind closed doors.” Today, Côté has found happiness again with the Quebec-born singer Sophie Vaillancourt. But the story doesn’t end here.

Just one day after his final bow with The National Ballet on June 5, Burn Baby, Burn by Côté Danse will run June 6 to 8 at Toronto’s Bluma Appel Theatre before embarking on an international tour. Featuring pulsing disco beats, the electrifying production tackles climate change through dance. “I worried about the timing,” Côté admits, “but then I realized it is working out just perfectly.”