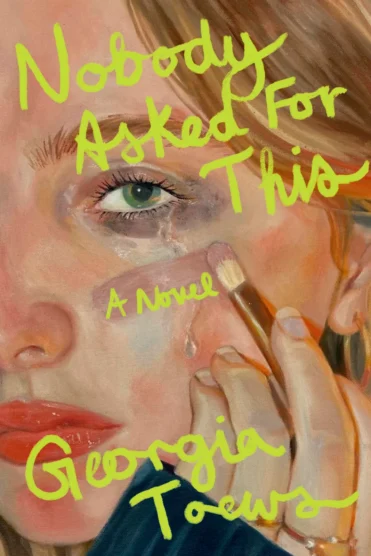

Georgia Toews on Her Latest Novel, Nobody Asked for This

Gripping writing that grapples with complicated relationships through a comedic lens.

Georgia Toews has a special fondness for Jimmy’s Coffee on Toronto’s Ossington strip, so much so that an order there kicks off her new novel, Nobody Asked for This. Toews almost wrote an interaction with the barista, who also serves us when we meet there in March, into the opening, before her editor advised her otherwise. “I want to be able to come back,” Toews says, laughing.

I doubt that would ever be in jeopardy. In person, Toews is as engaging as she is on the page. Nobody Asked for This is set in Toronto’s comedy scene, which is where you could find Toews before she turned to fiction. One would think that with one of Canada’s most beloved novelists, Miriam Toews, for a mother, her daughter might have tried fiction first. But perhaps unexpectedly, it took her awhile to warm up to her mother’s books. At eight or nine, growing up in Winnipeg, she recalls trying to read A Boy of Good Breeding, her mother’s 1998 novel about the fictional Algren, Manitoba, “Canada’s smallest town,” and its eccentric cast of characters. “I remember my father running up the stairs and yanking it out of my hands like, ‘That’s not appropriate for you!’” She also remembers her family keeping a Canadian Book of Lists in their bathroom; one of Miriam’s novels was listed for having one of the “Top 10 Sex Scenes in Literature.” At 13, nothing could have been more off-putting. “I went, ‘I’m not reading my mother’s smutty novels!’ Of course not.”

Toews only returned to her mother’s books in her first year of art school. It was a time of personal turmoil. School wasn’t working out as she’d hoped, and her parents were separating. Reading her mother’s novels became a way for Toews to feel close to her. By being swept up in her imagination, Toews recognized her mother’s voice and some of the real-life hardships that influenced those deft, sensitive stories. “I’ve loved reading her books ever since then. It’s always kind of bittersweet, especially knowing, as I know now, how much of you goes into the fiction. I’m incredibly proud and obviously amazed at her skill, but I’m also like, ‘Oh no! Don’t feel that!’”

Today, they’re very close, both personally and physically. “I mean, she lives in the laneway house,” Toews quips of her mother, who lives in Toronto with Georgia, her husband, and their two young sons, as well as Miriam’s mother. “I see my mother every day. If I don’t see her every day, then I have to text her. And we’re both the type of people that text with a lot of exclamation marks, so if we don’t text each other with a lot of exclamation marks, then one of us will show up at the other’s house that’s 10 feet away and be like, ‘Are you okay? Are you mad? Are you good? Are we good?’”

After dropping out of art school in Montreal, Toews auditioned for the National Theatre School and Studio 58. When she didn’t get in, she told her parents she was going to backpack across Europe. “And they didn’t understand that, because I had no job or money or, you know, reasonable way to get there.” Instead, her family convinced her to move to Toronto, where she enrolled in Humber College’s comedy: writing and performance diploma program. “I always enjoyed comedy. Improv was my favourite thing to do in theatre, so it just seemed like a natural fit.”

While she thrived writing sketches, Toews found performing terrifying. “I would kind of just black out and disassociate but get through.” She only turned to standup because it was the most accessible outlet for her writing. Soon she was enmeshed in the comedy scene, bartending at venues, dating comedians, and even briefly moving to New York to seriously pursue it.

___

Although Toews put a lot of herself into standup, it was never quite right. “But I still wanted to have a creative outlet. I still wanted that sense of play and joy. Fiction seemed like the safest medium where I could have fun and process and explore.”

She explores all of that in Nobody Asked for This, which follows Virginia, a 23-year-old standup comedian, as she works her way through Toronto’s comedy scene and toward similar goals as the author herself once had: moving to Los Angeles and chasing American success. While Virginia hones her comedic instincts, she also contends with some serious hardships, including growing out of old friendships and into a new relationship with grief. After experiencing sexual assault, she finds herself reconsidering how and why she turns to comedy, when it heals, and when it hurts.

Toews is no stranger to tough subjects. Her debut novel, Hey, Good Luck Out There, was inspired by her own relationship with addiction and recovery. Its publication sparked multiple conversations with old friends who had witnessed that intense time of her life. “They had a lot of questions for me, these women that loved me, that supported me. We had our falling-outs during my times of addiction, and then we came back to each other. And I wanted to get into that more, what it means for women to go through that sort of thing.” With romantic breakups, there are scripts. Toews wanted to find the language to discuss what happens when friendships fall apart. “I wanted to approach it with a tenderness that maybe I don’t extend a romantic relationship. Friendship breakups are just as important and intimate and tragic.”

For her second novel, she wanted to consider how we process trauma in friendships. The heart of Nobody Asked for This is Virginia’s relationship with her childhood best friend, Hayley. When we meet them, arguing over a Jimmy’s Coffee order, what was once a supportive and fulfilling friendship has become fraught. Toews teases out the nuances of a souring friendship: the ways you want to hold on, the ways you fear you’ll both change, and the painful necessity of allowing yourself to become someone new. It’s something she learned as she came out the other side of addiction. “I had so many friends say, ‘Oh, you’re back to the old you. We missed this version of you.’ And it was confusing for me, too, because I was like, ‘Well I don’t feel like the same person I was prior to going through this,’ and I want that to be okay. I want the new woman I’m working on, that I’m trying to live in, to be supported, to be accepted for what I am today rather than some memory of the woman I was before. I don’t want to go back to being 14,” she says, sliding easily from insight to punchline. “Fourteen-year-old me made some very questionable choices.”

And while Toews is indisputably funny on the page, she’s reticent to claim the adjective, even within her own family. She and her husband have arguments over who’s funnier. Her children are hilarious, as is her brother, the author and academic Owen Toews. And then, of course, there’s her mother. “I mean, there are articles about how funny she is. She’s famously funny. So I can’t really confidently be like I’m the funniest one. I think I’m the loudest. I think I prefer to write scenes and dialogue and comment on the funny people, but maybe not be one of the funny people. It was actually hardest to write Virginia’s comedy, because I didn’t want it to be my own standup,” Toews says. She also focused on capturing tensions she observed in the comedy scene, with keen attention to what Virginia, as a young woman, would come up against from herself and her peers.

___

“The jokes these comedians are making, the process of making jokes, they can be hurtful. They can be offensive. It was an interesting practice of trying to be funny but also trying to find a balance of what is honest, what is reflective of what comics are actually talking about. The novel wasn’t a full-on joke jam or me trying to be as funny as possible. The audience has to do a lot more legwork, because standup is so much about performance.” —Georgia Toews

While Toews doesn’t think the standup in the book is necessarily the funniest you’ll ever read, it’s a thoroughly honest account of someone performing in, watching, and navigating the comedy scene.

Whether writing about rehab or toxic relationships, honesty remains key. Like Toews experienced with her mother’s books, one imagines her own sons will have a bittersweet time when they’re old enough to read their mother’s novels and reckon with her blend of sensitivity and wit. It’s a combination Toews finds unavoidable—and also necessary. “The world is so funny and so terrible. I really enjoy writing about people living in the aftermath of it all.”

She might write about motherhood next, even though the sheer volume of emotions involved terrifies her. Whatever she writes, one doesn’t doubt that it will continue to be messily, joyfully sincere. As she exits Jimmy’s and waves goodbye to the barista, I can think of worse fates than being a character in a Georgia Toews novel.

Photographed on location at Neighbourhood Studios Sterling House, Toronto.