The Dream-like Art of Marcel Dzama

Diving into the spectral influences behind the artist’s work and his latest solo show Ghosts of Canoe Lake, on a cross-Canada exhibition tour.

Marcel Dzama photographed in his Brooklyn studio.

“I have been keeping these bad, kind of Dracula hours,” Marcel Dzama divulges when I ask how his day has been so far. “I go to sleep at 7:30 a.m.,” he says, explaining that he nods off just after his son heads out to catch the school bus. While Dzama’s extreme nocturnality is a lifelong habit—he attributes it to a prehistoric gene imprinting from “whoever stood guard at the cave in the nighttime”—this was a late night, even by his standards. He tells me about the large, three-panel drawing he promised to complete in time for Art Basel that has been forcing him to burn the twilight oil.

“It’s a giant flood, with creatures, and there’s a Spanish guitar player,” he starts. “It kind of has that feel of nature taking over—or ending.” This new work, then, continues exploring the climate-related concerns he is also investigating in Ghosts of Canoe Lake, the first major exhibition the Winnipeg-born, New York-based artist, now 50, has had on home turf in more than a decade. After debuting at the McMichael Canadian Art Collection in Kleinburg, Ontario, this past December, the suite of 40 new paintings, drawings, collages, and a film runs until October 27 at Contemporary Calgary, then travels to Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art in Winnipeg from November 22 to March 8, 2025.

Ghosts of Canoe Lake makes explicit reference to the Algonquin Provincial Park site of Group of Seven contemporary Tom Thomson’s drowning. In 1917, the body of the promising landscape painter was discovered in the lake, tangled in fishing line and with head wounds commensurate with the forceful strike of a paddle. Ever since, the Canadian art world has been obsessed with the mystery of his unsolved death.

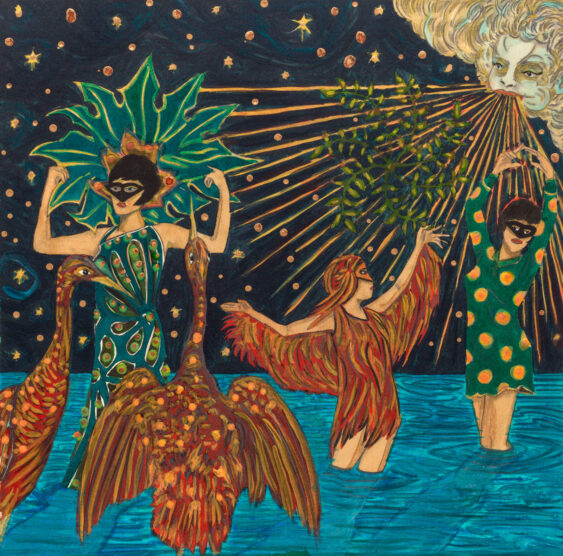

Marcel Dzama draws from folk vernacular and Dada whimsy to create dreamlike works on paper including, Ghosts of Canoe Lake, 2023, 36.2 x 36.2 cm.

Dzama’s exhibition wrings out the waterlogged conspiracy theories and revives Thomson as a new member of the cast of merry players that inhabit his artwork. Lions and cats and bears cavort alongside figures in polka-dotted leotards who got their spots from Dada artist Francis Picabia. The midnight sky is speckled with golden stars, and the landscape is lush with jack pines, but almost every scene is threatened to be consumed by either fire or flood. Thomson returns to the site of his death, and the enormity of the problem of environmental catastrophe pulls the artist under once more.

If this imagery seems the stuff of dreams, or maybe nightmares, that’s because it often is. In the past, Dzama has kept a Moleskine notebook beside his bed to record his subconscious visions, but lately he’s been making voice recordings on his phone instead. I picture him like the artist in Francisco Goya’s 1799 aquatint The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, slumped on his table amidst his pencils, paintbrushes, and ink pots, a swarm of owls, bats, and a lynx rising behind him.

___

“My best ideas usually come when I am half-asleep, half-awake,” he says. “Or in the shower,” he laughs, “but I can’t jot those ones down.”

Lately, everything Dzama paints has been awash in blue, thanks to a month-long trip to Morocco he took with his family in 2018 after a particularly intense period of work. He had finished his project The Most Incredible Thing with the New York City Ballet, had a show with frequent collaborator Raymond Pettibon, and made a film all within half a year, and was feeling burnt out and open to new beginnings.

“There’s a city called Chefchaouen, and it’s all blue,” Dzama recalls of the painted town he visited in Morocco’s Rif mountains. It was spring, when the pink moon was hanging low and large in the night sky. “My son and I were walking to the kasbah there, and it just looked so huge. It was so magical,” he says of the moon. The trip “opened up my mind to colour more.” Before then, Dzama worked mostly in “flat colours, red and brown and earth tones,” but “the way the light was in Morocco, it just made everything appear more brilliant than in my regular life.”

Marcel Dzama (b. 1974), Waiting on Tom’s Ghost, 2023, 36.8 x 36.2 cm.

Dzama grew up in Winnipeg, where jewel-toned natural wonders and architectural splendours are not found in abundance. In 1996, during his final year at the School of Art at the University of Manitoba, where he was a founding member of the Royal Art Lodge collective, there was a fire at his parents’ house. The blaze gave his dad severe burns, suffocated his pet rabbit, and reduced a lot of the young student’s artwork to ashes. The insurance company put his family up at a hotel, and it was on Airliner Hotel stationery, in a palette of scorched hues, that Dzama drew his thesis project. “I think I had maybe $11,” he remembers, “so I was just using the cheapest supplies I had.”

Dzama’s professor, Alison Norlen, introduced his drawings to Plug In Institute of Contemporary Art curator Wayne Baerwaldt, who selected them for inclusion in a group show in California. The work sold out (to lucky collectors who nabbed them for $20 a pop), a Los Angeles Times critic lauded his work as “simultaneously sweet and demented,” and Dzama, then living in his parents’ basement, got gallery representation at Richard Heller Gallery in Santa Monica. In 2004 he moved from Winnipeg to New York, and he is now represented by global behemoth David Zwirner Gallery as well as Sies + Höke in Düsseldorf, Germany.

That tragic fire set his career off on a trajectory it might not have otherwise taken. Before then, he says, “I was doing more messy, big paintings.” (Terminally self-deprecating, Dzama jokes that part of what Baerwaldt might have been drawn to with his thesis project was that it was “very cheap to ship.”) After Dzama moved to New York, his drawings became more heavily populated, and his compositions began to resemble theatrical stage sets or chess grids. He didn’t find his way back to Canadian art until the pandemic hit, and he started painting trees en plein air in the manner of the Group of Seven and Tom Thomson. He dug up some books to use as reference points, but “I barely knew anything,” he admits. “When I was younger, I really disliked landscape drawing. I was more into Dada and Fluxus and that sort of thing.”

Marcel Dzama (b. 1974), Detail from the triptych After the Fire, Before the Flood, 2023, pearlescent acrylic, ink, watercolour, and graphite on paper, 28.3 x 43.2 cm.

When McMichael Canadian Art Collection curator Sarah Milroy reached out to Dzama about doing an exhibition of his political works, he asked if he might investigate Canadian landscape painting instead—no less fraught a subject, after all. During the pandemic, Dzama and his family camped out at the U.S.–Canada border, anxiously awaiting an opportunity to spend time with his wife’s father, who was ill. In the news, there was a war starting in Ukraine, where Dzama’s ancestors had emigrated from, and unmarked graves had been found at residential schools, which his wife’s family had been forced to attend. Perhaps he felt the need to reckon with his family’s history. It was time to come home.

In Dzama’s painting Grandmother Passing the Ecstatic Forest in a Swarm of Star Light, he references stories told to him by his grandmother, a nurse and midwife, who would walk home at night while cougars were out prowling. Danger is always lurking in the shadows. In the film To Live on the Moon (For Lorca), the artist adapts a screenplay written by Spanish surrealist Federico García Lorca in 1929. “I tried to use as much of the Lorca script as I could, but a lot of it was very, very aggressive. It was early surrealism, where they seem to kill animals a lot, and there are a lot of almost-rape scenes. I was like, I don’t really want to do that,” Dzama says. “In one of the scenes in Lorca’s film, a priest molests a schoolboy, and so in my version this character is in that situation, but the moon rescues him. Then the priest’s head kind of explodes.” Dzama cast the head in question out of papier mâché, making something approximating blood and brains out of spaghetti and condoms full of chocolate sauce. “We painted a watermelon to look like the moon and dropped the watermelon on top of this head,” he giggles.

Marcel Dzama (b. 1974), Grandmother Passing the Ecstatic Forest in a Swarm of Star Light, 2023, pearlescent acrylic, ink, watercolour, and graphite on paper, 33 x 33.7 cm.

With the film, “my two obsessions kind of came together,” he says, referring to the figures of Lorca and Thomson, the latter of whom Dzama plays in a plaid shirt and pipe. He notes that “there were a lot of similarities” between the two men. While Thomson’s disappearance on Canoe Lake is still shrouded in question marks, it’s often alleged that his sexual orientation and political beliefs played a role in his untimely death, as they did with Lorca, who was assassinated by General Franco’s fascist militia in August 1936 at the start of the Spanish Civil War.

___

Dzama’s ever-present interest in themes of revolution and oppression stems partly from his own experience of growing up in working-class Winnipeg. “There’s such a rich history there. There was a general strike in 1919—it was the closest thing to a communist revolution in North America,” he says of his home city.

His studio in Winnipeg was in the Exchange District, which had its heyday in the 1910s and 1920s—around the same time that Thomson was pushing his oar out into Canoe Lake for the last time. The downtown area’s buildings are painted with so-called ghost signs: palimpsests of advertisements for products such as stomach powder, canned ham, chocolates and candies. Before his career took off, Dzama used to shop at Goodwill and Value Village, which he says were full of products from that era, such as Sears catalogues that he would use for drawing inspiration. “It really felt like some sort of ghost of that time period was still haunting the city,” he says.

Marcel Dzama (b. 1974), The Sisters of Nature, 2023, pearlescent acrylic, ink, watercolor, and graphite on paper, 36.2 x 36.2 cm.

“I’ve never seen a ghost,” Dzama tells me with a hint of regret, “but I have had that feeling that something was in the room with me. I used to live in this house in Saskatchewan that felt like it was definitely haunted. It was in the middle of nowhere, in this town called Fosston,” he says. Without witnesses, it’s impossible to say what belongs to the realm of fantasy and what is merely fact. Perhaps the presence Dzama felt that night was an unsettled spirit—a lonesome painter, for instance, who sought to kindle an obsession in the mind of a younger artist who might keep his memory alive. Perhaps truths are less important than the myths they inspire. “I mean,” Dzama reminisces, “it could have just been that I was staying up until five in the morning.”

Artwork courtesy of the artist and David Zwirner ©Marcel Dzama.