The Creative Worlds of Contemporary Artist Elizabeth Zvonar

Multimedia explorations.

Elizabeth Zvonar creates so contagiously and with such enthusiasm that everything she touches seems to turn to art. At her compact home and studio in Vancouver’s Strathcona neighbourhood, she pulls out a shoebox with the disassembled remains of Apotropaic Magic, an oversized and brutalist charm bracelet with bronze-cast trinkets covered in gold leaf and shaped like a toilet paper roll, a bunch of herbs, a head of garlic, and a tree gall hanging from an industrial chain. She encourages me to handle the pieces, to explore the texture and quality of materials. It’s a way of engaging with what she creates and an excitement for sharing her work that makes viewing her art feel participatory, even when looking at a 2D piece on a wall.

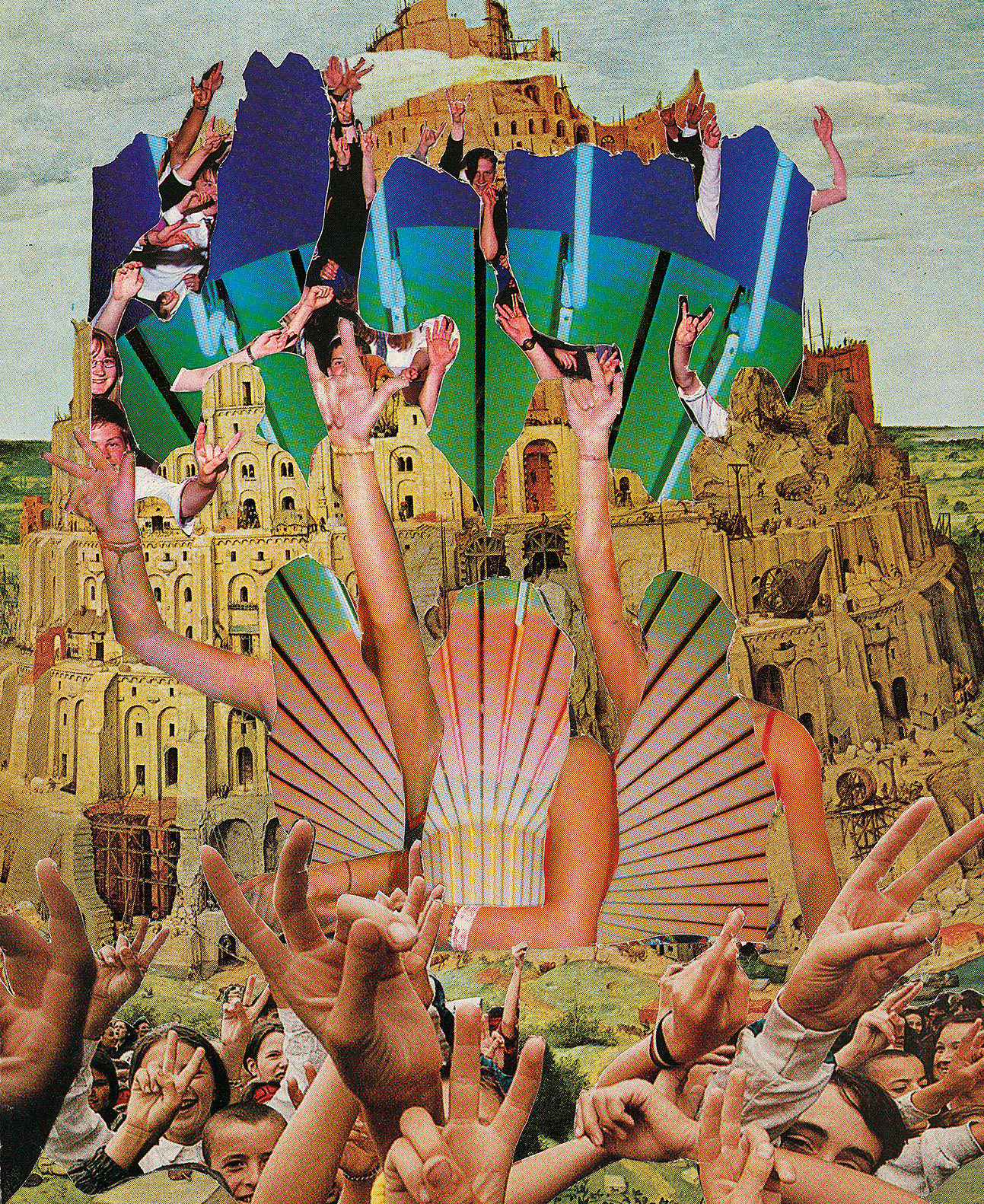

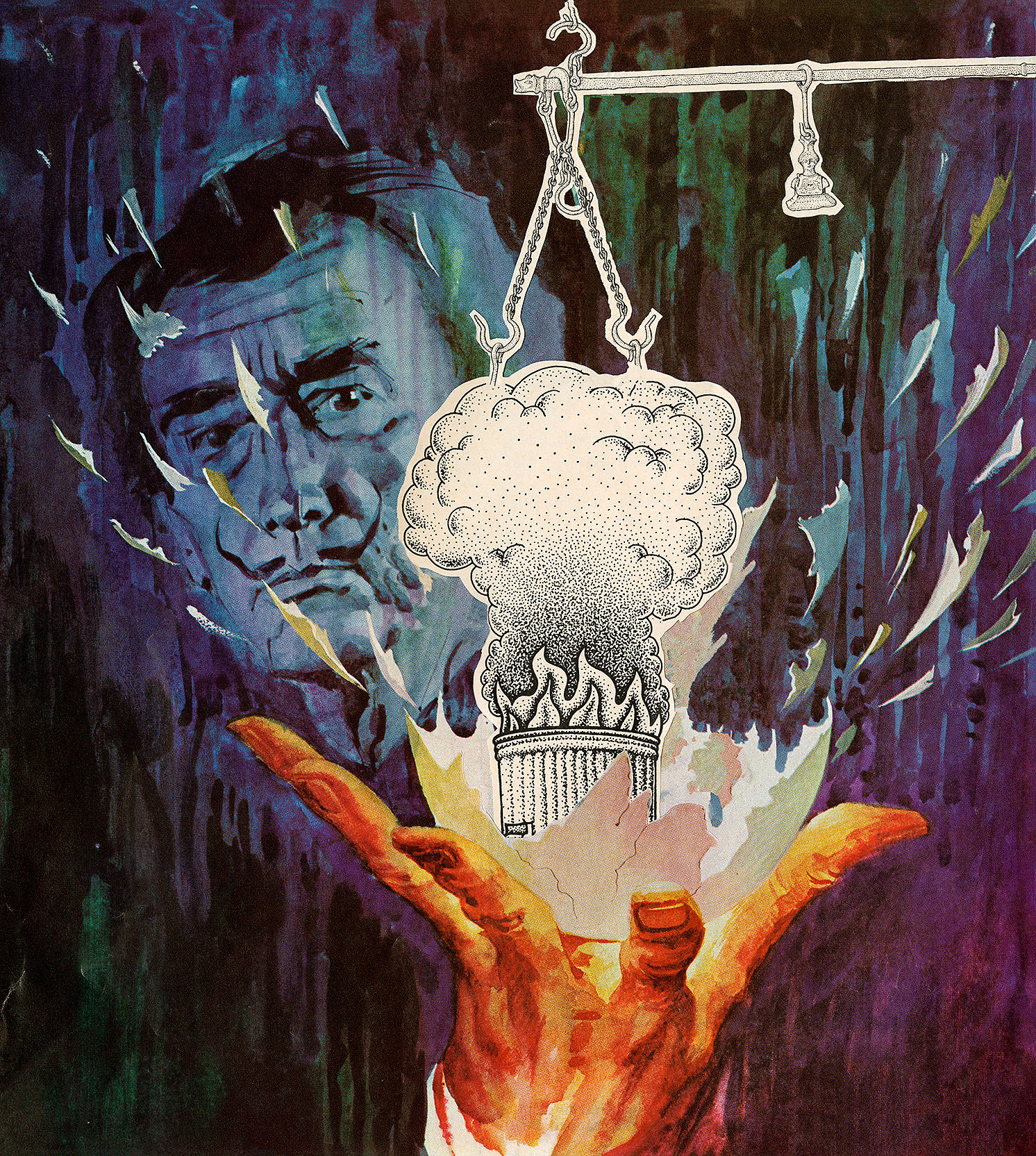

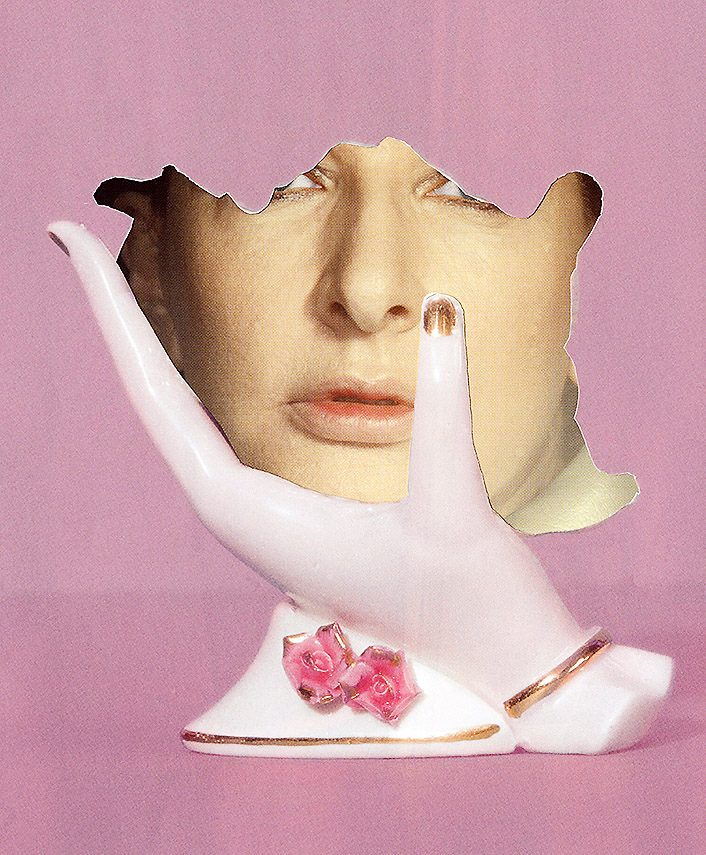

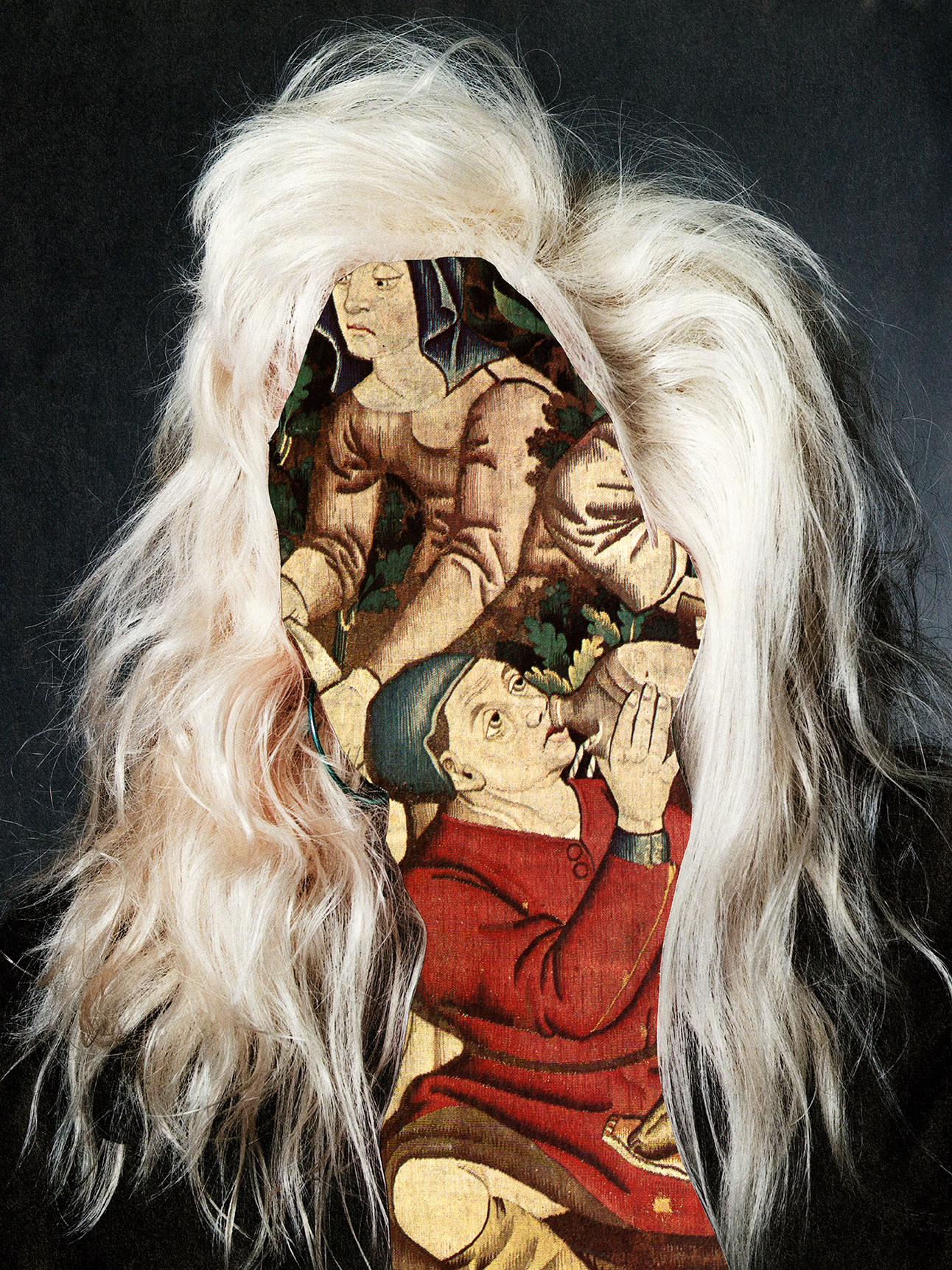

Most of Zvonar’s work is collage and assemblage, which she usually makes in Photoshop, piecing together unlikely images to create surrealist, often unsettling compositions with bright colours and blended textures. “I like the layers, and I like making things that have multiple perspectives and potential viewpoints,” she says. “That keeps me interested.” She approaches her work with a heavy dose of curiosity and a willingness to let her intuition guide her. To viewers, her work often seems like a scientific experiment gone wrong—an owl with hands holding a spoon (Storyteller), a woman’s head slit down the middle to reveal a glittering ruby beneath (Visionary Feminist), or an egg, cracked open to show an egg within an egg within an egg (Lucky). Some creations appear simple, with just a few carefully chosen parts, while others are made up of hundreds of pieces, including her own collages within another collage, so each time the viewer sees something new.

Before Apotropaic Magic was relegated to a shoebox, it was part of Zvonar’s most recent solo exhibition, Knock on Wood + Whistle earlier this year at Audain Gallery at Simon Fraser University. The collection explores themes found throughout her work—consumerism, the human quest for spiritual fulfillment, and the commodification of the female body—along with her fascination with talismans and tokens meant to ward off bad luck.

Growing up in Thunder Bay as the youngest of five, Zvonar wasn’t exposed to a lot of art, and certainly not the type she creates now. Still, her mother encouraged her creative spirit. “I used to take all the old cardboard boxes and make strange worlds out of them, and my brother would freak out and be like, ‘Oh, she’s ruined the living room again,’” Zvonar recalls. “There is a story in the family that she [my mom] pulled my brother aside once and said, ‘I think she’s creative. I don’t know what this is, but I think she’s great.’”

Zvonar didn’t immediately gravitate toward fine art, because being able to create hyper-realistic depictions of a still life or other everyday objects seemed bizarre. It was studying art history that opened her mind to the expansiveness of the creative world. “Once we got to the 20th century, it was like, Oh, maybe people were just messing around and doing all kinds of things and it’s about ideas. Then I saw the potential, and I was like, ‘Oh, I could actually maybe do that.’”

Artworks from her most recent solo exhibition, Knock on Wood + Whistle, Elizabeth Zvonar explores spirituality and the depiction of the female body in Western art.

This flame was fanned in her early 20s when she went to France to au pair, her first time out of the country. It opened the possibility of working while travelling, and she later had adventures across Asia and Europe, taking whatever jobs she could—picking grapes in the South of France, pouring beers at a pub in London, teaching English in Seoul. Throughout, she continued to make art, though she didn’t know where it would take her long term. While studying studio art at Capilano College (now Capilano University—she had moved to B.C. with her family when she was 16), she received a scholarship to study in Toyota City, later returning to Japan to study for six months in Sapporo at Hokkaido College of Art & Design. “Being a regular 20-, 21-year-old, or whatever, I was pretty fearless and left unscathed.” Her travels gave her a perspective into the professional art world, especially Charles Saatchi’s controversial London Sensation exhibition in 1997. “I stood in line like everybody else and waited to go in. And I think that was an aha moment for me, where I was like, oh, these are people that are 30, 40 years old, because you could read their bios and see their ages, and they’re making these crazy projects.” It was a glimpse of what a life in art could look like.

“Definitely it was the Sensation show where I was cognizant of the fact that there was a possibility. It didn’t feel like that here in Vancouver. Although there were a lot of working artists, at that time I was too young to connect with any of them. And it was only after I came back and started going to school and stuff that I started to see what was going on here.”

For those who look closely, it’s evident Zvonar draws from a deep pool of knowledge, both of art history and the world, which adds layers of dimension to her work. “I go through lots of magazines all the time, old ones, new ones. The last six months, there’s been a real surrealism kick in advertising of contemporary fashion,” she says, pointing to de Chirico and Magritte references. “I’m fascinated with how art history keeps coming into our everyday. Most people don’t know where it’s sourced from or are interested or even care where it’s coming from. And I get excited when I can recognize it.” She adds these references to other artists into her work, along with others across time and place, like Pompeii’s lesser-known neighbour Herculaneum or 16th-century reformer monk Martin Luther.

_________

For those who look closely, it’s evident Elizabeth Zvonar draws from a deep pool of knowledge, both of art history and the world.

Though common themes can be found throughout her work, Zvonar doesn’t set out to make a statement—it’s engrained in the materials she uses. “I think it’s just already there in the content, and then I’m just using that content,” she says. “It’s already in its DNA, all that stuff, because I’m grabbing it from these publications. It’s just what we’re socialized to visually understand.” It allows viewers to follow their own intuition, just as she does when she makes it, and create a personalized viewing experience.

A bronze-cast purse hanging from a large hook, titled History, Influence, New Bag, could point to the inherent inhumanity of capitalism or the constant emotional baggage women bear in consumerist cultures. But Zvonar is nonchalant, saying it was a pretty bag that got a stain and the hook was the most practical way to hang it. “It sort of fell into the category of just this object that wasn’t going to get used,” she says. Never really knowing where the artist places meaning, walking a line between intention and happenstance, only adds to the surrealism and dissonance in her work that make it incredible and evocative.

Her practice is often guided by what she finds—in a magazine, at a flea market, in an art history textbook, at Home Depot (a favourite spot for sourcing materials). A beloved pair of worn-out pink work gloves or a duffel bag with a broken clasp (the other bag in the series) are reimagined to say something more as art. In every stage of her work, she takes what she knows and sees to build something completely new.

When Zvonar first entered the professional art scene in 2002 after graduating with a BFA from Emily Carr University of Art + Design, collages of her scale were not widely done. “For Vancouver, it was relatively new. And I don’t know of anybody actually who blew things up. A lot of people have made collage over the years, but it’s all tabletop stuff and quite small.”

For Zvonar, size isn’t a constraint. One of her largest and probably most widely seen projects was a billboard collage for the Scotiabank Contact Photography Festival. Positioned on Toronto’s busy Gardiner Expressway in 2019, Milky Way Smiling is a galactic scene with a curving glowing light. Expecting something very busy, the organizer pushed back on her initial prototype for the project, saying no one would get it. “I don’t know if there’s much to get,” Zvonar says. “If you’re on that route, and you’re sitting in front of that billboard every day for three years, eventually you’ll laugh. That was all I was asking for, that if you give somebody enough time, they’ll smile.”

_________

“Through the work that I’m making, I am trying to get people to stop and contemplate for a minute outside of their screens or being distracted from a conversation.” —Elizabeth Zvonar

ISPY, Courtesy of the artist.

Storyteller, Courtesy of the artist.

Carousers, Courtesy of the artist.

Many of Zvonar’s pieces are laced with a tongue-in-cheek humour. If it’s not immediately apparent, check the titles—Nutsack isa cement cast of shelled nuts in a bag. Louis’ Legs shows a close-up taken from a painting of King Louis XV’s leg cut into a person’s silhouette. “Through the work that I’m making, I am trying to get people to stop and contemplate for a minute outside of their screens or being distracted from a conversation,” she says.

These days, she is represented by Daniel Faria Gallery in Toronto and stays busy. Among others, she’s had solo exhibits at the Polygon Gallery, Daniel Faria Gallery, Burrard Arts Foundation, and Vancouver Art Gallery Offsite and has shown internationally in New York, Australia, Japan, and Belgium. Her work will be featured in Phaidon’s upcoming collage volume, Vitamin C+, set to be released next year, and in December she’ll take part in the Southern Alberta Art Gallery’s The Faceless Familiar, which examines the contemporary manifestations of surrealism.

With a keen eye for placement and design, Zvonar continues to make engaging and diverse work that pushes the bounds of what we know. “The goal for most people is to define exactly what they do and then use that to sell their art. They brand themselves as the person who is making comments about the environment or whatever, which is great that people are trying to get so specific for themselves, I guess,” she says. “But I don’t find that interesting, as an artist trying to make things. I don’t want to brand myself.”

As a result, she doesn’t pigeonhole herself into a specific label or group, not because of a bloated sense of ego that no one word could properly describe her genius (though this isn’t untrue) but because she seems to enjoy exploration and imagination far too much to stop with one. “All I can say is, I make art and I like making sculpture and I like making collages. And I like making objects that are cool, that make people stop and look and think about something for a minute.”

Hair and makeup by Becca Randle. Assistant photographer Kitt Woodland.