Interior Design of the Mind

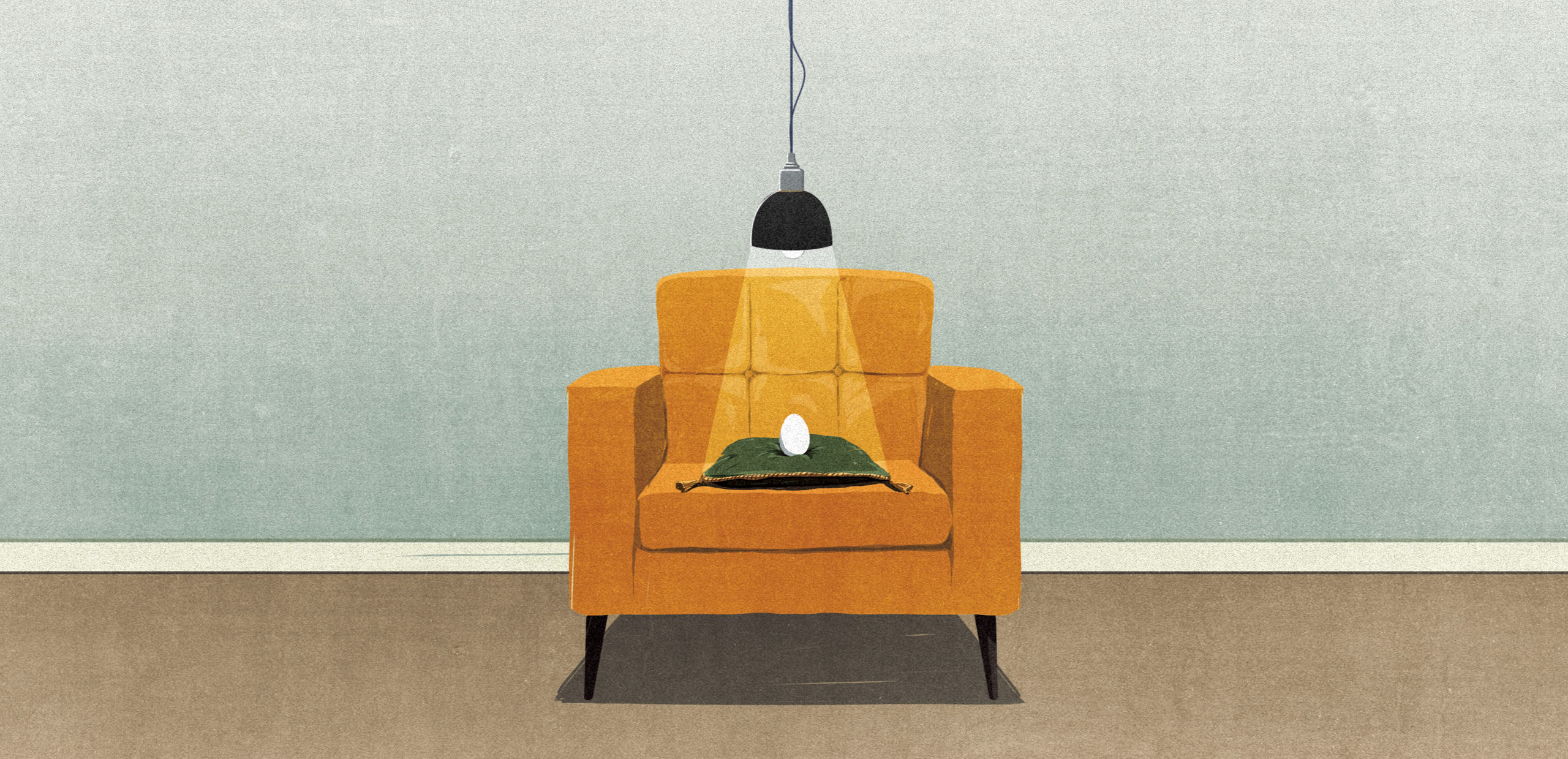

Chamber of reflection.

Sitting still in a bedroom, one sees the light playing off the surfaces of the dresser, of the door ajar. A vague recollection of the same scene—at different times, with different light—bubbles up in the corners of the mind. Versions of past selves are embedded like ghostly roots in every corner of the space. Memories on top of obscured memories—what the poets call a palimpsest.

Dwellings have long been used as surfaces on which we print memories. The ancient Greeks and Romans built mind palaces as mnemonic devices to remember speeches—a trick that contemporary gurus of self-improvement have revived. But, for those of us who aren’t orators or memory masters, the way we organize our intimate, physical space has a lasting relationship with the way we think and experience life. As we build our private worlds, particularly after extended periods inside because of the pandemic, consideration of the spaces we decorate and arrange is key to the work of self-reflection. But how?

The French philosopher Gaston Bachelard was an early proponent of examining this relationship between dwelling and mind. In his treatise The Poetics of Space, Bachelard theorized a poetic sense of physical spaces that originates in a child’s early experience with their house, suggesting that the dwelling becomes a projection of the mind and a sort of incubator for the imagination. For the child, the house is the “first universe, a real cosmos in every sense of the word.” Our early relationships with our childhood spaces then inform the way we think and arrange our subsequent houses, and even our lives. Bachelard examines writing across different cultures to see how poets have used metaphors of the house to locate memory, and he highlights the feelings of isolation and the amplification of thought that take place in a house in deep winter, when the dwellers are unable to leave—a feeling many have experienced for the first time while in quarantine.

Influenced in part by circumstance, a house or a room, your space, is an intimate one; a mirror placed because of a gut feeling or a shirt kept can stand in for places, things, people—memory. We all know the relative who keeps things for no apparent reason, who becomes emotionally attached—for some, throwing something out of the house feels very much like forgetting—and not all cherished memories are strictly joyous. People measure eras of their life by the houses they lived in. There’s also the feeling one gets when they walk into the house of another, as if they have walked into a thought bubble that conceals an array of intimate secrets.

A friend once told me that she is constantly surprised at the odd things she finds while working as a post-incidence responder for houses that have been flooded or caught on fire. Her job involves sifting through people’s most intimate things, boxing them up, and then trying to reorganize them once the premises has been cleaned and restored. She spoke of how uncomfortable it can be to see the inner workings of people’s lives, as if overhearing something personal in a public place or being confided in by a stranger. She told a story about the uncanny feeling of hopelessness at trying to reorganize the contents of a hoarder’s home. Her experience probes into the feelings we get when we encounter hoarders in media reports, but it’s hard to articulate why it makes us uncomfortable. Just as certain people make us uneasy, while others make us open up.

Our experiences of life are different when they happen solely from home. The poetics of space, the rhythms of our steps through the rooms of our house are expressions of our thought. Time spent at home, considering spaces, redecorating, asking ourselves why we have things in certain places are forms of subconscious reflection.

If the house is a universe of our earliest devising, as Bachelard suggested, and if people have always learned from and projected desires, dreams, and fears onto the stars, then the house, too, is more than just a dwelling. Trends in design come and go, as does cultural sentiment, but the way that a house expresses an individual remains, part of us. The changes that we’ve made to our homes during the pandemic, the altering and noticing, certainly has bearing on the changes we ourselves have undergone.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter, here.