-

Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West by Blaine Harden.

-

The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson.

-

The Cleanest Race by B.R. Myers.

-

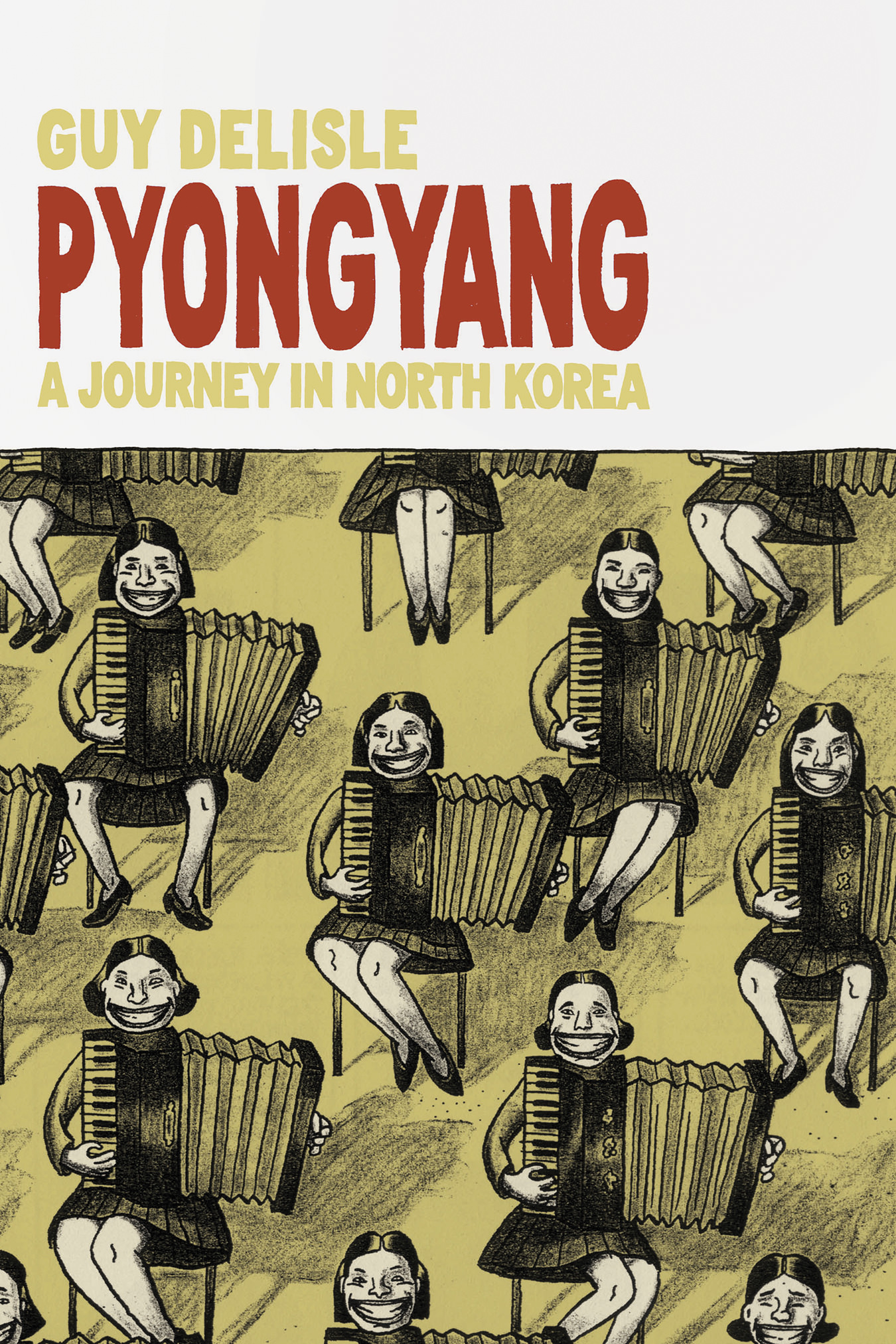

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea by Guy Delisle.

Off the Shelf: Tales from the Hermit Kingdom

Books By Blaine Harden, Adam Johnson, B.R. Myers, and Guy Delisle.

The term hermit kingdom is an odd one. There’s something almost fantastical about it—which is fitting, since the country it usually describes, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, is frequently presented as being so enigmatic. In the mainstream media, news about North Korea often is as bemused as it is breaking. Much of this stems from our own misconceptions and lack of information, which is perhaps unsurprising given the guarded nature of the regime. Yet the past decade or so has allowed us the occasional glimpse through the country’s heavily restricted borders. Here are four books that take very different approaches to trying to describe what goes on in one of the most insular countries in the world.

Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West

In Escape from Camp 14: One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West, journalist Blaine Harden tells the story of Shin Dong-hyuk, a North Korean defector who escaped from the infamous Kaechon internment camp, also known as Camp 14. You may have heard of Shin, who has made the rounds in the media recently, talking about his experiences and his escape from the prison camp in 2005. His journey from growing up in such an environment—and in fact being born there—to becoming an advocate for human rights is an extraordinary one.

Shin’s father was imprisoned after his two brothers—Shin’s uncles—fled south during the Korean War. This is far from an uncommon occurrence, Harden notes: “Guilt by association is legal in North Korea. A wrongdoer is often imprisoned with his parents and children. Kim Il Sung laid down the law in 1972: ‘[E]nemies of class, whoever they are, their seed must be eliminated through three generations.’” Shin was born after his parents met in the prison through a “reward marriage”, given out as “the ultimate bonus for hard work and reliable snitching.”

Shin was different from many others in the camp; he had never seen anything outside the electrified barbed wire fence until he escaped at the age of 23. “Unlike those who have survived a concentration camp, Shin had not been torn away from a civilized existence and forced to descend into hell,” writes Harden. “He was born and raised there.”

And it is indeed hell. Prisoners face widespread disease; “issued a set of clothes once or twice a year, they commonly work and sleep in filthy rags, living without soap, socks, gloves, underclothes, or toilet paper.” There are routine beatings and torture; at one point, Shin’s teacher “beat a six-year-old classmate to death for having five grains of corn in her pocket.” And the perpetual threat of starvation is such that “roasting rats became a passion for Shin.” The almost constant torment that’s described can result in a sometimes overwhelming reading experience. As it should be.

Yet through the darkness is light in the form of Shin’s escape, after which he made his way to China and then South Korea, where he first met Harden. However, his integration into a more normal society is difficult, as is detailed in the later chapters. Even after his escape, Shin is not quite free; he remains haunted by the known fates of his mother and brother, who were executed after being caught trying to flee when he was 14, and the unknown fate of his father, who he expects would have been tortured following Shin’s successful escape.

Escape from Camp 14 is an unflinching look at the abject misery of life in a cruel, unforgiving environment. But it’s a story that is important to hear, given that “North Korea’s labor camps have now existed twice as long as the Soviet Gulag and about twelve times longer than the Nazi concentration camps. There is no dispute about where these camps are. High-resolution satellite photographs, accessible on Google Earth to anyone with an Internet connection, show vast fenced compounds sprawling through the rugged mountains of North Korea.” Also distressing is the dedication that opens the book: “For North Koreans who remain in the camps” (which the U.S. State Department and some human rights groups estimate to be “as high as two hundred thousand”).

The Orphan Master’s Son

The Orphan Master’s Son, Adam Johnson’s astonishing Pulitzer Prize–winning novel, begins as the coming-of-age story of Pak Jun Do, a young boy growing up in North Korea. After being raised in an orphanage run by his father, he is recruited in the military as a young teenager. “Jun Do, at fourteen, became a tunnel soldier, trained in the art of zero-light combat”; he is tasked with patrolling the tunnels underneath the Korean Demilitarized Zone, checking trip wires and looking for intruders.

Later, Jun Do is assigned to a group that kidnaps people from the beaches of Japan to bring back to North Korea. (Like many aspects of the story, this one is based on fact.) One of his first targets is a singer; Jun Do’s superior tells him, “The Tokyo Opera spends its summers in Niigata. There’s a soprano … Some bigshot in Pyongyang probably heard a bootleg and had to have her.” These encounters—so indicative of the frivolity with which human life is treated—prove to have no small emotional bearing on Jun Do.

Following the book’s first half, which has its climax in an almost unbearably tense diplomatic mission to the United States, the story experiences a startling shift in nearly every sense. Suffice it to say that the twists and pacing of the plot are rivalled only by Johnson’s exceptionally descriptive writing and outstanding ability to make us so heavily invested into the fate of Pak Jun Do.

The story is an emotional reflection on the paranoia, heartbreak, and suffering inflicted on those who find themselves on the wrong side of the country’s regime. But what gives it a spark of optimism is its enduring faith in the freedom of the human spirit, even in the midst of what the author, in an illuminating interview included at the end of the book, calls “a trauma narrative on a national scale.”

The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves—and Why It Matters

In The Cleanest Race: How North Koreans See Themselves—and Why It Matters, B. R. Myers examines North Korea’s use of propaganda, first in terms of the country’s history and then via the common and recurring themes invoked by the regime.

Much is made of the historical basis for North Korean propaganda (which has its origins when the country was under Japanese rule in the early 20th century) as well as the distinction—and Myers believes there’s a significant one—between communism and North Korea’s reigning ideology. But more fascinating to me were the assorted details concerning the society’s beliefs, as explained by the propaganda. An example is the conviction that “to be uniquely virtuous in an evil world but not uniquely cunning or strong is to be as vulnerable as a child.”

The Cleanest Race is, as expected, more academic than the other books described here. But in separating the propaganda from the issue of human rights, Myers is able to take a more clinical look at the way in which North Koreans view both their country and the rest of the world. And part of that is about clearing up our own misconceptions. We may not understand the reason for the massive statues and structures built in Pyongyang, yet “propaganda is never a mere waste of money, and its whole point is to make people feel as significant as possible.” We may use terms like brainwashed to describe the citizens, yet Myers maintains that the personality cult is naturally “much harder to swallow when regarded in isolation” and in reality “proceeds from myths about the race and its history that cannot but exert a strong appeal on the North Korean masses.” We may puzzle at the depictions of Kim Il-sung as a blank-faced boy before understanding that “because true Korean spontaneity ends where an intellectual expression begins, Kim is never shown thinking.” And Myers sums up Juche—that omnipresent but rarely described ethos that allegedly binds the country, but which the author calls a “sham doctrine”—in one sentence: “The Korean people are too pure blooded, and therefore too virtuous, to survive in this evil world without a great parental leader.”

Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea

In Pyongyang: A Journey in North Korea, Guy Delisle looks at the country from the perspective of a visitor. Delisle, a Canadian animator, lived in Pyongyang for two months while working for an animation company. He illustrates his trip in this graphic novel, which is absorbing in its depiction of the various quirks of being a foreigner in such a place.

Some of the best moments in the book come from Delisle’s observations of the daily life. He notices that the ubiquitous (and mandatory) portraits of Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung “have a wider edge above than below,” which eliminates any reflection and “also intensifies the gaze in this face-to-face encounter.” (Delisle adds, “There’s a detail Orwell would have liked.”) He visits the local department store, which resembles “an installation at a contemporary art museum”: all endless aisles of identical shoes, buckets, and pots. He is annoyed by the constant music propaganda.

Delisle stays in one of the few hotels for foreigners, a “massive 50-storey tower with a revolving restaurant” (although “all foreigners are on the 15th floor, the only one that’s lit”). Forever trailed by his guides, he takes delight in minor acts of rebellion. He tries to convince one translator to borrow his copy of Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. He amuses himself by making paper planes and flinging them from his hotel window, trying to make them reach the nearby river. He sings Bob Marley’s “Get Up, Stand Up” to one of the technicians in the office.

Also humorous are his constant exasperation at apparently arbitrary restrictions and the various “field trips” Delisle’s guides subject him to, including visits to the International Friendship Exhibition and the Children’s Palace. Well complemented by Delisle’s drawings, the story can be very funny, but there is a subtly sinister aspect to many of his experiences.

Late in the story, almost in summary of his time in the city, he asks, “To what extent can a mind be manipulated? We’ll probably get some idea when the country eventually opens up or collapses.” It’s a question that’s germane to how we in the West view the country, and one that, when answered, will explain so much about a place that remains so isolated.