-

Karen wears a Lida Baday dress, available at the Bay and Maxi Boutique in Toronto, Ashia Mode in Vancouver; Pierre Hardy shoes, available at Zola Shoes. Jewellery: Chopard Puskin diamond earrings, available at Royal de Versailles Jewellers.

-

Karen Kain in Swan Lake. Photo by Andrew Oxenham.

-

Karen wears a shearling coat and sweater from BOSS Black, www.hugoboss.com; Escada pants, at Escada boutiques in Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver. Jewellery: Chopard diamond necklace, Royal de Versailles Jewellers.

-

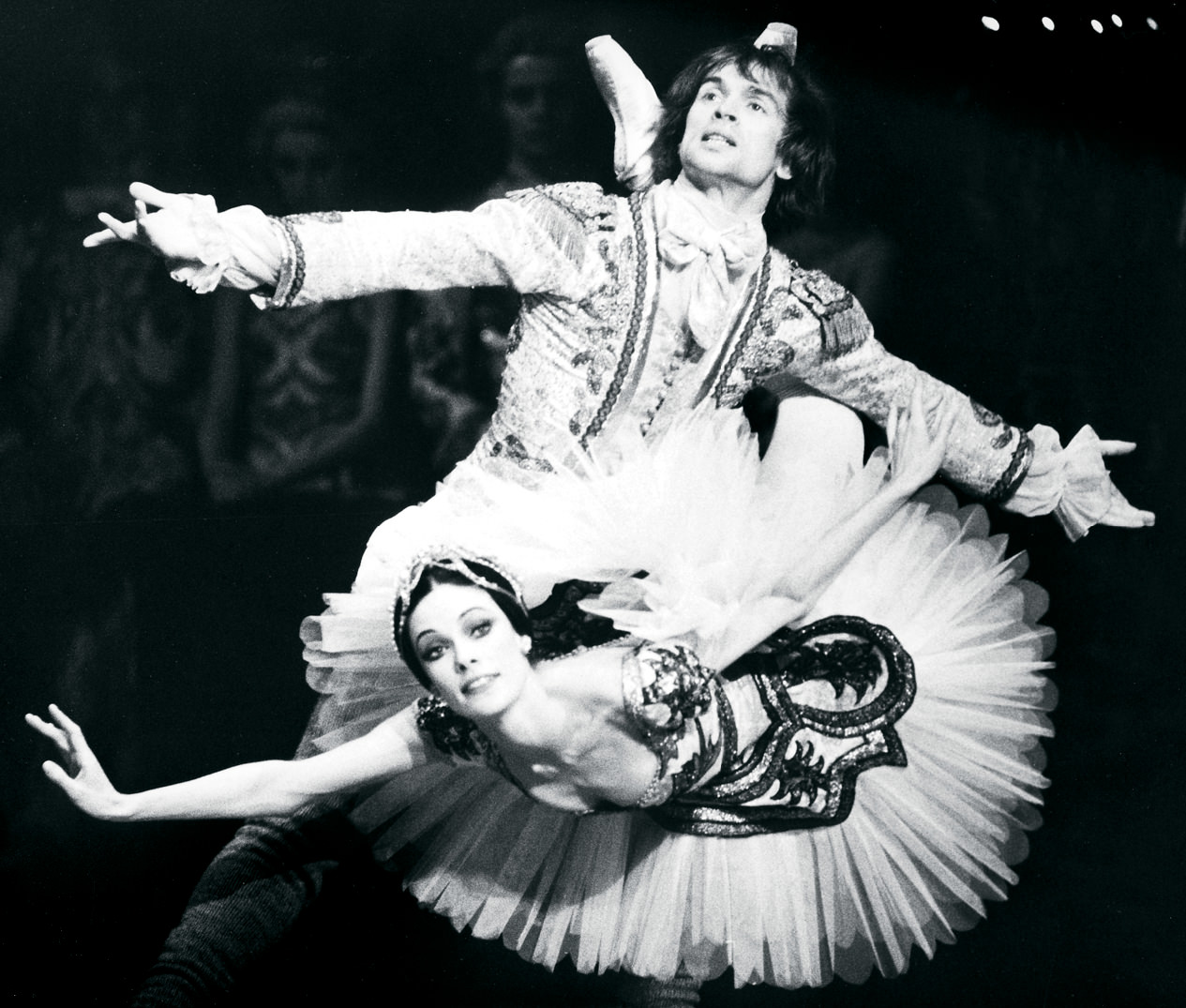

Karen Kain and Frank Augustyn in The Sleeping Beauty. Photo by Martha Swope.

-

Karen Kain and Rudolf Nureyev in The Sleeping Beauty.

-

-

Karen wears a BOSS Orange dress and leather jacket, www.hugoboss.com; Cesare Paciotti shoes, available at Zola Shoes. Jewellery: Chopard Happy diamond earrings, Royal de Versailles Jewellers.

Karen Kain Leads the National Ballet

Great expectations.

Karen Kain has had one season under her belt as Artistic Director of the National Ballet of Canada, and her report card is an A+. The morale of the dancers is good, subscriptions are up, patrons seem satisfied, and the company even posted a small surplus to set against its $1.2 million debt. Kain, now 55, has also shown she can make the tough decisions that come with the territory. “I bring who I am to the job,” she says. “I’m honest, caring, hard-working and I know the milieu. I’ve spent my whole professional life with this company. I’ve worked under every Artistic Director and I know the contributions that each one made. No one has a greater sense of the big picture than I do.”

That she was offered the position of Artistic Director when James Kudelka stepped down was no surprise. Kain was clearly being groomed for the post since retiring from the stage after a glittering 28-year career as one of Canada’s most beloved and honoured ballerinas. She became artist in residence with the National in 1998 and was appointed Artistic Associate in 1999. At first she was involved in fundraising and liaising with patrons and the corporate elite. When her talents as an administrator became evident, she joined the artistic staff, coaching dancers, staging ballets and advising Kudelka on casting and repertoire. Says Kain: “I loved learning about the complexities of a large ballet company, and that’s when I started to think that I might like to become Artistic Director.”

Born in Hamilton, Ontario, but raised in the Toronto bedroom community of Mississauga, Kain is the eldest of four children. Her father was a senior vice-president of Westinghouse Canada. Fraternal twins Sandra and Susan are an emergency-room nurse and exercise therapist, respectively. Kevin is a doctor of tropical medicine. “As a collection of people,” says Kevin, “we don’t show a lot of outward bravado. We tend to under-promise but over-deliver.” Kevin’s wife, Cathy, feels that the close-knit Kains share a fire in the belly that won’t let them rest on their laurels.

Kain has had a lifelong love affair with animals and thought about becoming a veterinarian. When she was eight, however, she saw the National Ballet perform Giselle with Celia Franca as the tragic heroine, and her passion for dance was ignited. The wannabe ballerina moved to Toronto when she was 11 to attend the National Ballet School. By 1969, the year she joined the company, Kain had grown into a statuesque 5-foot-7 dancer with perfectly arched feet and beautiful long legs.

The next season, Peter Wright set The Mirror Walkers on the company and gave Kain a soloist role. Former National ballerina Veronica Tennant recalls an excited Kain rushing back to the dressing room after a visit to “Miss Franca”. Unhappy with being back in the corps de ballet, Kain had asked Franca if she could have a small role in the upcoming Swan Lake. Instead, Franca had given her the lead role of Odette/Odile. Kain made her debut at 19 in Swan Lake replacing an injured Tennant. A star was born, and Kain was promoted to principal dancer in 1971.

In 1972, Rudolf Nureyev set Sleeping Beauty on the National and Kain became his favourite partner. The great Russian dancer made Kain’s international reputation by performing with her all over the world. 1972 was also the year her fabled partnership with Frank Augustyn began at the National. Kain needed a tall man to partner her and Augustyn was pulled from the ranks. In the 1970s, she was a frequent guest with Roland Petit’s Ballet National de Marseille and in the 1980s with Eliot Feld’s New York-based company.

Kain accomplished in her career what few dancers have ever been able to do. She was a ballerina who became a household name in a country obsessed with hockey players. In fact, her brother, Kevin, compares her to Wayne Gretzky in terms of public adoration. “Gretzky did something he loved and he did it well,” he says. “Karen was the same: excellence without ego. They were both motivated by the purest of reasons.” Kain also strongly believes in the public responsibility of celebrity. In 2004, she became Board Chair of the Canada Council but has never been a ceremonial figurehead. Rather, she has vigorously lobbied for greater funding for the arts.

“I loved learning about the complexities of a large ballet company, and that’s when I started to think that I might like to become artistic director.”

Being an national icon, however, does not necessarily convert into being a successful CEO, and some people wondered if Kain had the backbone to be an Artistic Director. Former National Principal Dancer Rex Harrington was Kain’s partner for 18 years, and he knows she has the right stuff. “Karen’s personality from the outside is a puff pastry,” he says. “I know her from the inside because a dance partnership is like marriage without the sex. We had tremendous fights because she knew what she wanted artistically and wouldn’t budge. Believe me, you don’t want to be on the other side of her temper.”

John Alleyne, now Artistic Director of Ballet British Columbia, is a former National soloist. Says Alleyne: “Karen is seen by the public as the beautiful girl next door that everyone wants to love, but beneath that mask she has what all great artists have; passion and drive. Watching her rehearse was both a revelation and an inspiration. She navigated an incredibly successful career through strategic planning and left the stage more popular than ever. My instincts tell me that the National will have a rich run under Karen.”

Tennant feels that Kain showed strength in her career choices. “Karen accepted invitations to guest abroad even though it wasn’t the National’s policy,” she says. “I turned down engagements because I was frightened of Miss Franca.” And then there is the story about how the CBC acquired a sprung floor. “When Karen and Frank were filming Giselle, she refused to dance on cement. None of us, not even Baryshnikov, had spoken up about it before. I remember her saying one day in the dressing room, ‘I know my worth!’” As Kain’s closest friend Marley Sniderman wisely points out: “Karen’s innate goodness and sweetness should never be equated with lack of inner fibre. This is the woman who, in the final years of her career, kept a plastic tub with ice water in her dressing room so she could submerge her feet to keep the swelling down at the end of a performance. It was excruciatingly painful, but she did it because she had to.”

Kain can be brutally honest, both about herself and others. Former National soloist Linda Maybarduk has known Kain since their ballet-school days and experienced her candour first-hand. “I was having a difficult time in my life,” she explains. “Others let me wallow in my troubles, but one day at the barre, Karen barked out, ‘Until you become more positive, I don’t want to be around you!’ It was like a bucket of cold water, but it turned my life around. She had the courage to say the truth when no one else would.”

The downside of being an international dance superstar is trying to meet impossibly high expectations. In the late 1970s, Kain suffered from clinical depression. She tried to make herself into a more perfect instrument, but all she saw were her own imperfections. She lost the joy of dance, which manifested itself in lacklustre performances. Kain rallied by putting herself through two harrowing years of intensive therapy. “Her comeback is an amazing story and a real act of courage,” says her brother, Kevin. “It shows she can handle speed bumps.”

The early years of Kain’s marriage to Ross Petty also went through a crucible of fire. Born in Winnipeg, Petty had built up a very successful career as an actor and singer in both New York and Europe. The two had met briefly in 1981, and when Petty returned to Toronto in 1982 as the lead in the national tour of the Stephen Sondheim hit musical Sweeney Todd, he invited Kain to the show. The chemistry was immediate. The couple married in 1983 after Kain proposed. Petty was 36 and she was 32.

Penelope Doob, Chairman of York University’s dance department, helped Kain write her 1994 autobiography Movement Never Lies. “What Ross didn’t realize,” she says, “was that he had become the husband of public property, and that no one was ever going to be good enough for Canada’s sweetheart. People wanted Karen to be Mary Pickford and not a grown-up with a sex life.” For his part, Petty did not want to be known as Mr. Kain. “We began our shared life in the public eye which was a big burden,” he says. “I had worked very hard to build up my own career and I couldn’t help feeling resentment. I had moved to Toronto for Karen, and now I was facing a wall of hostility.” Adds Doob: “On the other hand, Karen was slow in comprehending just how the constant putdowns were affecting Ross.”

“Karen is seen by the public as the beautiful girl next door that everyone wants to love, but beneath that mask she has what all great artists have; passion and drive.”

Things came to a head at the infamous “roast” to celebrate Kain’s 20th anniversary with the National. The other speakers poked gentle fun at Kain, but Petty’s speech was deemed vicious and inappropriate. As former National ballerina Vanessa Harwood says: “Ross thought he was being witty, but he seemed to be making fun of her and people were infuriated by his bad taste. If she had left him the next day, everyone would have applauded.” Kain, however, took her wedding vows seriously. “I wouldn’t have stayed in a bad marriage,” she says, “but Ross put himself into therapy and faced his demons. I have the best part of him now, and I couldn’t be Artistic Director without his support.” In 1988, the couple suffered another blow when Kain had a miscarriage. As Petty says, Kain is a great partner, and they were able to work together to get through this melancholy time.

When Kain’s family, friends and colleagues look back over her life and times, they recognize the signposts in her professional and private life that have forged what Kevin Garland, the National’s Executive Director, calls Kain’s “shaft of steel”. Collectively they sculpted the artistic director out of the dancer. Cathy Kain sums up her sister-in-law with this mantra: “She loves her family, she loves her city and she loves the National.”

Kudelka is an acknowledged genius, but a dark and brooding one. Kain’s first goal as Artistic Director was to clear the air from Kudelka’s tenure, which by all accounts was toxic. As the irreverent Harrington says: “It was like, ‘Ding dong, the witch is dead.’ The dancers are genuinely happier because they don’t have to face the uncertainty of James’s moods.” Soloist Rebekah Rimsay has been a company member for 16 years. As she points out, the Kain reign thus far has been marked by constructive criticism, superb coaching and an open-door policy. Kain is also not a rigid martinet. At first she insisted that roll call be taken at company class, but relented when the dancers pointed out that sometimes their own individual warm-ups could be more beneficial. On the other hand, the ultra-sensitive Kain was able to take on the singularly unpleasant task of telling five dancers that their contracts would not be renewed. From Maybarduk’s point of view, when the nurturing, maternal side of Kain is at war with the professional side, loyalty to the company will win out every time.

The cornerstone of Kain’s artistic vision is to raise standards to the benchmark level of a classical ballet company. For Harwood and Maybarduk, who were with the company in the Nureyev glory years, the classical technique faltered as the repertoire became more contemporary under Kudelka. That Kain is opening her new season with a $700,000 refurbished production of Nureyev’s 1972 The Sleeping Beauty, that most quintessential of Russian imperial-style ballets, is a shot across the bow that the National dancers have to be able to perform classical technique at the highest level. Says Kain: “They have to be versatile, but they are classical dancers first and foremost. It is the classical repertoire that is the international measure of excellence.” The company is known for promoting from within rather than hiring at the top. Nonetheless, Kain has brought in Czech-born Zdenek Konvalina as principal dancer who has come from Houston Ballet following a notable career in Europe. Says Rimsay: “We’ve seen him in class and he has beautiful technique.”

Kevin Garland points to two new initiatives that demonstrate Kain’s proactive approach to her job. She has instituted a Dance/USA health program that is designed to reduce dancer injuries by 25 per cent. Every dancer undergoes an annual health assessment which identifies strengths and weaknesses, and is strictly confidential between the dancers and the medical-support team. To ensure that emerging choreographers are not just creating in a vacuum, the National’s choreographic workshop is being replaced by a choreographic lab, mentored by Serge Bennathan, former artistic director of Toronto’s Dancemakers and a former Petit dancer. The works created in the lab will be given studio showings which means that the wannabe choreographers can take risks without worrying about a public performance.

For the 2006/07 season, Kain is taking the company into Toronto’s long-awaited new opera house, the Four Seasons Centre for the Performing Arts. While the audience will rejoice over the superb sightlines and excellent acoustics, Kain faces serious problems. The National is a tenant and has to pay rent. Longer seasons mean more dancers and orchestra services. It will cost the company a bottom-line increase of $1.4 million just to move house from the Hummingbird Centre. In fact the annual operating budget jumps from $17 million to $23 million. Kain’s repertory choice for the first season, although a judicious mix of audience appeal and dancer challenge, contains only one new original work. She also has to find the money to tour so that the National can regain its international reputation. Kain, however, is painfully aware of the real possibilities of donor fatigue, government cutbacks and box-office slumps. Her main strategy is to build up the endowment fund while convincing governments to give tax incentives that encourage philanthropy.

Petty believes that it was Kain’s destiny to run the National Ballet. “She has no other agenda but this: that the National Ballet must be the best in the world. Karen possesses the winning combination of administrative skills, passion and artistry to pull it off.” And from Kain: “I want what’s best for the National. I want the decisions that I make to lead to excellence.”

Hair and Make-up: Gregory Graveline for Plutino Group. Shot at the Soho Metropolitan Hotel’s Penthouse Suite in Toronto.