Canuck Bard

Canadian soul.

I intend to travel a lot. My work as a musician requires it. Sometimes I go as far away as Europe, Thailand, New Zealand or Palestine, and for twelve years I lived all over the United States. But no matter how far I go I always feel like a Canadian away from home. That “Canadian-ness” goes so deep that it even informs the music I make. Thus, I’ve come to the following conclusion: There is something “Canadian” about Canadian music.

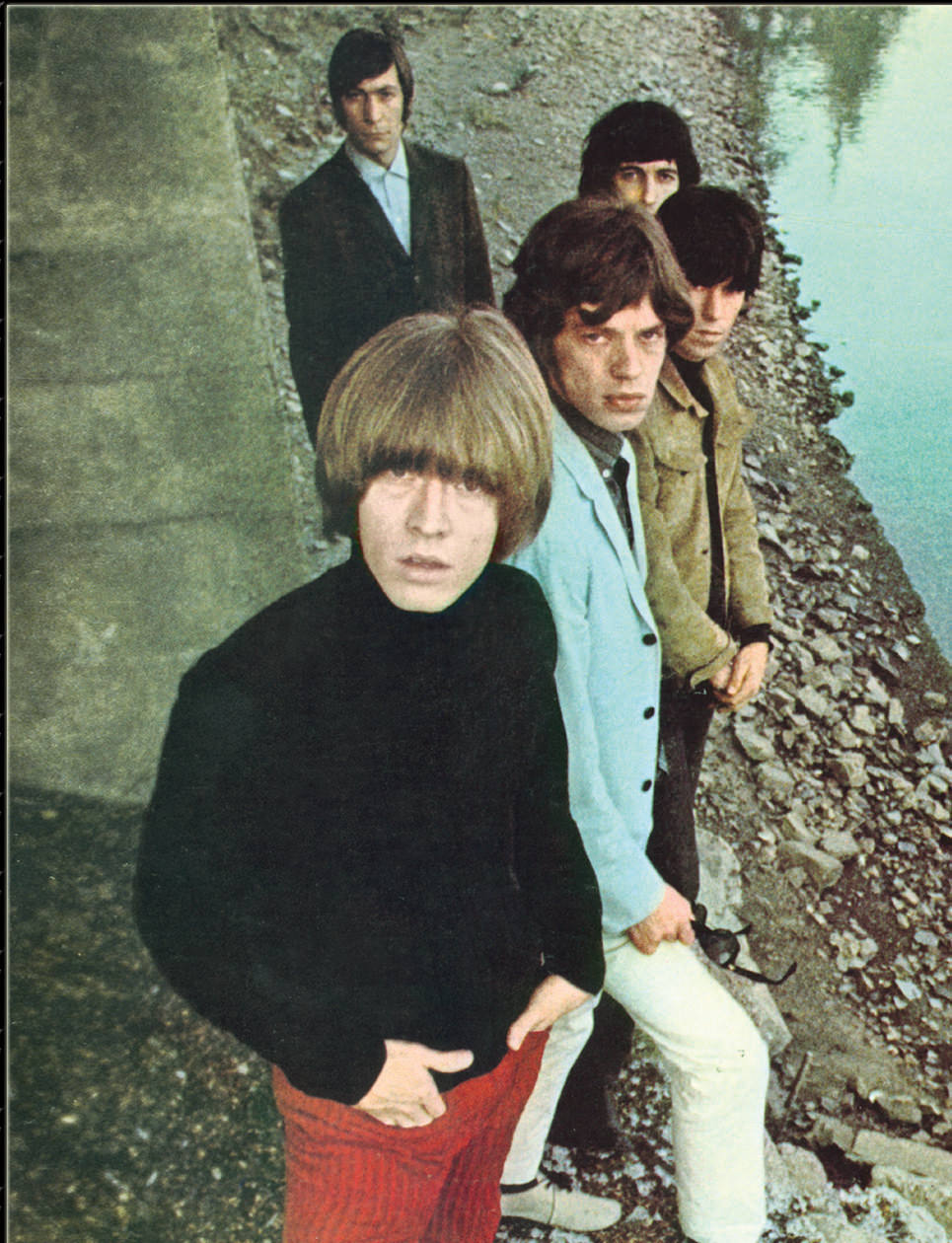

The problem is, we Canadians are programmed to look outward for international acceptance before we recognize the value of what is produced right here on our own permafrost. Sure, we can do commercial schlock with the best of them and those of us who blindfold and gag our inner Hoser long enough to attain that “region-less” dialect are sometimes rewarded with American dollars, or better still, euros. But the Canuck bards who are known for their writing mastery all share a high winsome sound so pensive and nostalgic it can wrench the hardened gut of a lone prairie coyote to tears.

Now, I’m not saying we don’t have a great deal of musical diversity in this country. On the east coast we hum in three four time while pulling salty lobsters from the sea while in the Canadian Shield we write heart-crunching wheat-ballads of lost love couched in farmyard metaphors. Maybe it has something to do with the boundless empty space that shrouds our cities or the whistling prairie wind or that we all secretly know we can escape up into the great untapped northern wilderness if things get too hectic down here. But no matter where one is on this vast land there is something signature Canadian about the way we make music and it’s recognized all over the globe.

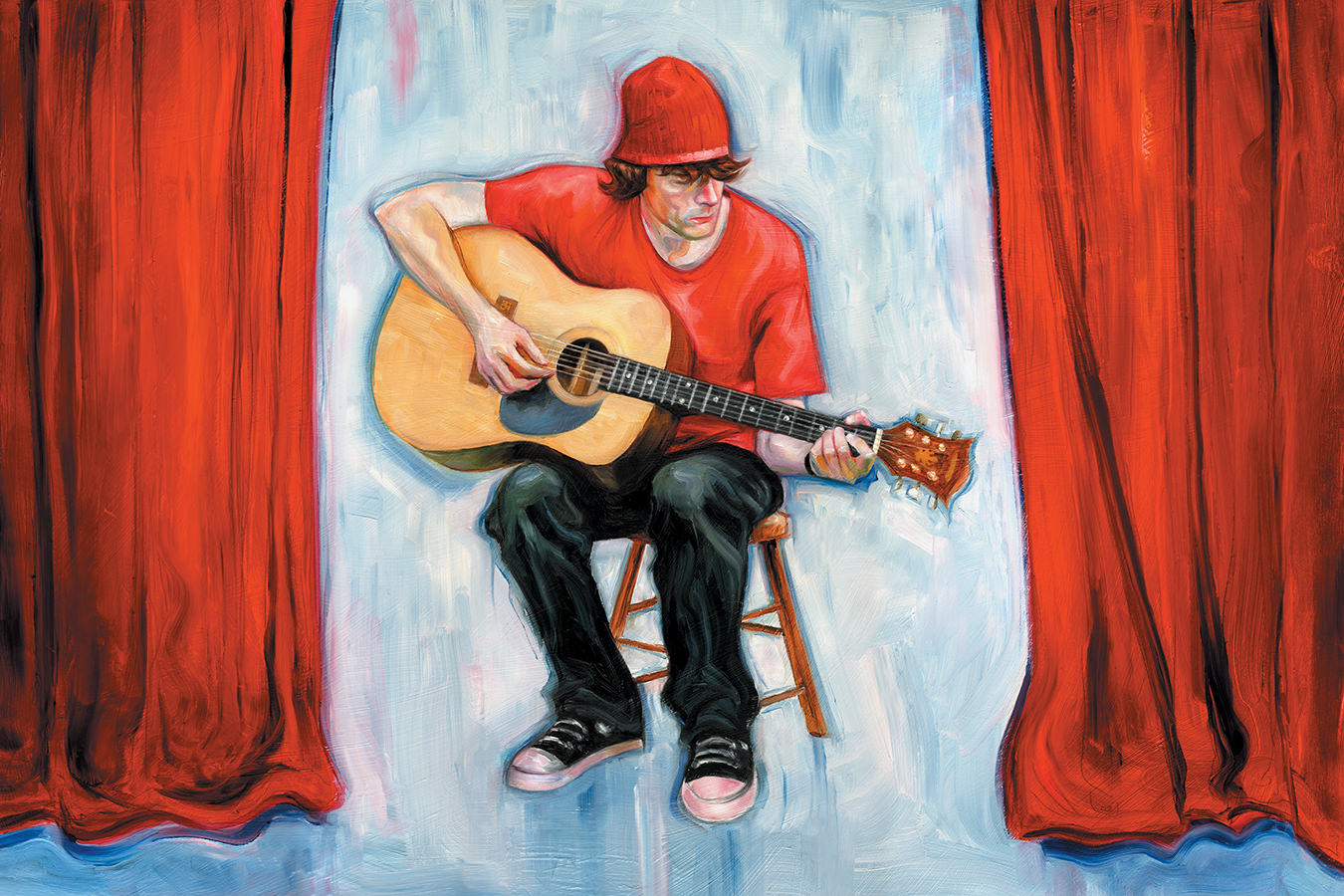

In my travels as a musician I’ve begun to gather clues and anecdotes as to just how this elixir of the Canadian muse tends to be received internationally. I remember strumming a swampy old acoustic guitar in Port-au-Prince, Haiti along with the shadowy Vodoun beats pulsing outside my window. There was a kind of magic in the mango-scented air as the fruit bats flew in and out of the window punctuating my every cadence with voiceless shrieks as if to taunt me. I was surprised to find that even surrounded by these intense primordial drum rhythms my chords still sounded like Trudeau doing a pirouette behind the Queen.

Being from Winnipeg, I’ve toured the prairies in winter many times and there’s a special place in my heart for barren moonswept tundra. Despite my penchant for the lonesome highway, however, I think there is something vital about the empty space between the chords of a Canadian-strummed guitar. No matter where you stand it bears a certain resonance, and weight, like frozen gravity. That big red maple leaf is hard to hide. It’s like a national archetype. The Balinese have the Gamelan, the Italian Baroque have their figured bass, and we have that high winsome sound. It’s what we do.

In some contexts Canadian music is almost a genre of its own. While living in the little town of Bethlehem in Palestine in ’97 I met an Oud player who showed me some ancient Arabic tunes. Then I played him a couple of my songs and “Long May You Run” by Neil Young. He said, “What is that, jazz?” I said, “no, it’s Canadian”.

Later that day I made my way into Jerusalem, six kilometres away, to buy an instrument from the great Oud master Mustafah al Kurd. I played one of my songs for him amongst the din of the street and the wafting fragrance of fresh falafel and before I got to the first chorus he shot back, “you paying in Canadian dollars or Shekelim?” Somehow he knew.

Last year I was on the shores of Raleigh Beach in Southern Thailand. While performing tunes all night for the drunken tourists after a couple of Red Bulls I heard one heavily accented voice in the darkness call out, “Kim, we’re down here, the Canadians are playing songs on the beach.” How she knew from our lyric-less strumming that we were Canadian I don’t know. Must be that high winsome sound.

More recently, I was on the Greek Island of Hydra, where Leonard Cohen “stood on the marble arch”. Accompanied by an entire Greek dance class, two nuns, a transvestite and a donkey, I reaffirmed my Canadian heritage by reluctantly performing a song I wrote as a 13-year old in Winnipeg to the tune of “O Canada”, to which the donkey replied, “know anyone in Toronto?” Apparently he had relatives living there.

Sometimes we underestimate how readily our Canadian-ness is recognized on an international level. Some inflections of our music find their way to the most unlikely places. While living in Auckland, New Zealand I often played shows with a local Kiwi band called Snap Attack. One night I launched into “Thunderstruck” in order to try and establish some “down under” cred but the audience would have none of it. They demanded something Canadian, so I broke into the first two lines of “Four Strong Winds” and then the crowd took over. They knew every word. Brought me to tears.

We Canadians often wonder how we are perceived abroad, especially in relation to our mighty neighbours to the south. I once asked a German guy in a small town just outside of Frankfurt what he thought was distinctive about the Canadian sound and how it differed from American music production. He said something in German about horses and lollipops that I didn’t quite understand. Maybe it was his particular dialect or maybe it was because he was only four years old but I did get the distinct sense that he was quite certain of his sentiment. It was obviously something he’d been thinking about.

Later that week I found myself in Interlaken, Switzerland yodeling backup vocals along with two mohawked alpenhorn buskers honking their way through a rendition of “Snowbird”. They had maple leafs shaved into their sideburns. My surprise at their knowledge of Anne Murray repertoire was eclipsed by their astonishment that Canada now had a two dollar coin so I flipped a toonie into their empty Alpen horn case. I think it was the only money they made that day.

Even in badly performed Canadian music something uniquely Canuck and magical comes through. Once, on the North Shore in Hawaii, I was performing solo on a Ukulele in a local café. A Hawaiian man came in just as I was flubbing the lyrics to a Joni Mitchell song so badly that he asked if I was French-Canadian. I figured he was half right so, in order to save face, I simply replied, “Oui,” and then headed for the beach.

Maybe we shouldn’t be so surprised when our national existence is acknowledged globally. After all, there is a great deal of talent in this country of ours. But the fact is, Canadians don’t play a particularly powerful role in this highly media savvy world. In fact, as residents of the northern reaches we often find ourselves above the media frost line and thus off the international radar so we tend to rely on the inner flame of our own soul for inspiration and affirmation.

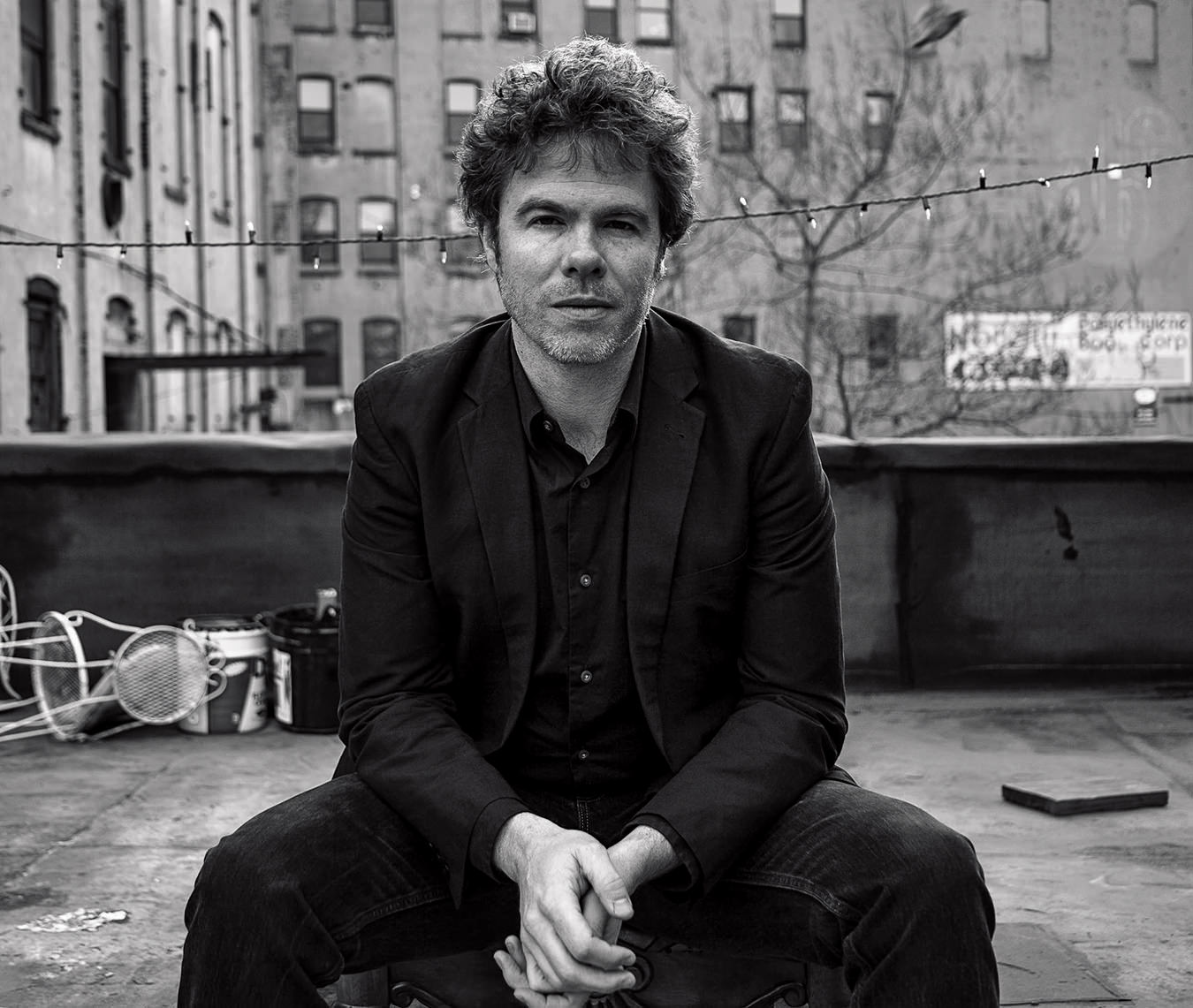

As Canadian songwriters we are tending the flame that was cared for by the Greats before us, such as Leonard Cohen, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, and many others, so we tend to have enormous faith in just what this land and its relative isolation can produce. But when the lead sled dog sniffs in our direction even our humble Canadian hearts swell with an understated sense of pride. I got to experience this recently when I attended a press conference in Toronto for the release of Gordon Lightfoot’s album Harmony. As Gordon walked in we were introduced to each other and after a few pleasantries he said, “Good work, Joel. Keep it up,” and then gave me the patented two-fingers-to-forehead salute. That’s when I realized that no matter how we as Canadians are received internationally what really hits home is when we are accepted on our own home turf.

You don’t have to be a shrill nationalist to feel the buzz of being appreciated in your own backyard. Bigger fame and fortune may lie out there across the vast open sea, but our Canadian soul is right here in our own ‘hood. That proud thump of your own heart, thrashing against your sternum as the hometown crowd calls for more, maybe that’s the real Canadian sound.