-

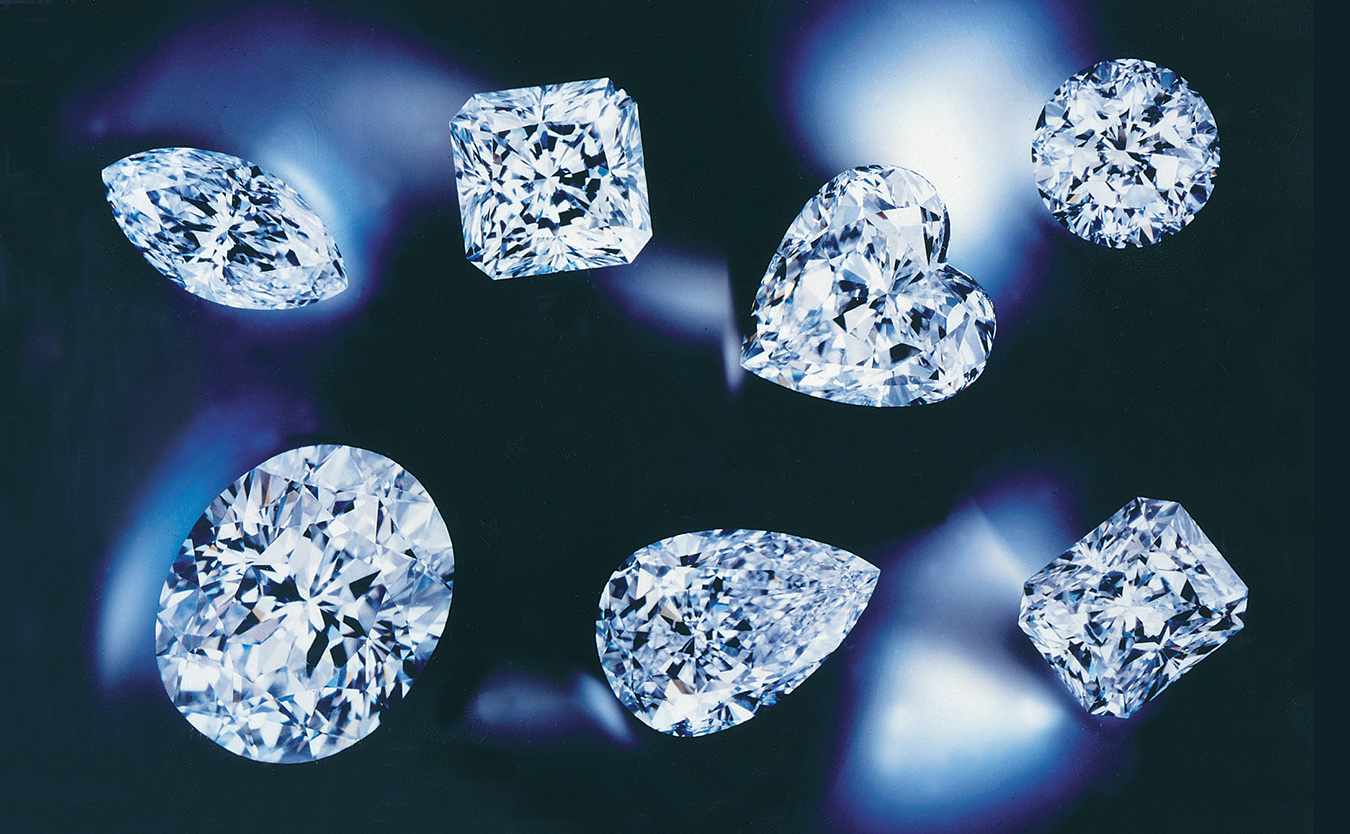

The Gabrielle diamonds, cut by Gabrielle Tolkowsky. Each features 105 facets.

-

The Duchess of Windsor’s panther brooch; the cat is perched upon a 152-carat blue Kashmir sapphire.

-

La Plume de Cyrano brooch, set with 348 brilliant diamonds, from the Birks Collection. Designed by Annick Lucier, winner of the 1998 DIA Award.

-

Snuff box decorated with 853 diamonds and 204 emeralds, from Palais Nacional da Ajuda, Lisbon.

-

Butterfly hair ornament from the Neil Lane Collection, Los Angeles.

The Lure of the Diamond

"Diamantes" exhibit at the Musée De La Civilisation.

All that glitters is not gold. This was understood very well in ancient India, where the substance that scratches all others, is scratched by none, was first discovered and named: adamas, diamante, diamond. It was conceptually called vajra, the thunderbolt, poetic nomenclature for highly compressed carbon, the hardest naturally occurring substance known to humans (yet extremely fragile, easy to shear off), conductor of heat, attractive to fat and grease, and to this day used far more for industrial purposes than those of design and beauty.

It may be more obvious that culture travelled from east to west in the forms of spices, cuisine and militia, but diamonds had a profound influence wherever they arrived. From India to the Mediterranean, from Shiva to Venetian artisans is a contorted path, barely traceable, if at all, but diamonds, as they have evolved through the centuries, will rarely if ever be on display in such an evocative, visceral fashion as they are this year at the Diamantes exhibit at the Musée de la Civilization in Quebec City.

What was the strict preserve of the Brahmin caste millennia ago eventually became the domain of the merely affluent; white and colourless diamonds in the twentieth century could be purchased (and it is fascinating that in our western world these purchases of say, 1901, are now fundamentally priceless, completing by a kind of limning logic the circle).

Visit the exhibit and you will see a Cartier brooch (1901) of gold fixed with nearly 2,000 diamonds of the highest quality. Not to be accurately evoked in its splendour on the page or in a photograph, this piece is stunning in its execution, a kind of perfection in stasis that plays hypnotically with the light afforded it. There is a Tiffany bow (1905), which in every way evokes the mastery of its famous designer. And these are two of many unique objects in the exhibit. Be prepared; be very prepared, and you will still draw in your breath at the sights. The Williamson diamond, an eponymous wedding gift from the Canadian geologist who discovered it to Queen Elizabeth II, and which she wore on the occasion of Prince Charles’s wedding to Lady Diana; Marie de Bourgogne’s engagement ring presented to her by Maximilian I of Austria in 1477; the tiara of Pope Gregoire XVI, which contains an array of 16,000 diamonds and precious stones; these soon will be a few of your favourite things.

It is easy to forget that Cartier, Fabergé, Tiffany and Birks were all jewellery designers, famous in their time and, if anything, more so today, as grandes marques. The cumulative effect of seeing three large Tiffany pieces circa 1900 together in one exhibit case goes well beyond the predictable. Yes, they had illustrious client lists, but seeing these pieces requires no imagination to understand why the British monarchy, French aristocracy, and such American houses as Morgan and Frick would seek out these artists.

Diamonds disappeared from the western world for over a millennium, as Christianity ascended and worriedly squelched them as being too talismanic, fragrant of other religions and therefore dangerous, evoking alternative views of the world and Godhead. However, as in many other things, Venice proved a fertile conduit for precious stones, a capital where the cutting of diamonds basically as it is practiced today was invented.

The importance of J.B. Tavernier’s travels in Turkey, Persia and India in the mid-seventeenth century are made clear here. His book on appraisal, including an insider’s view of the diamond trade, was not the first, nor is it truly a lapidary’s account, but it was highly influential in feeding Europe’s growing fascination with diamonds. He sold or gave stones of 20 or more carats on a regular basis, including what was originally called the Tavernier blue, known better today as the Hope diamond.

Articulated platinum and diamond bracelet from The Art of Cartier Collection, designed in 1937.

The legend of the Valley of Diamonds in Ethiopia was one of the more inventive and non-interventionist methods of controlling availability. The legend was that diamonds taken from this valley—purportedly the only source for fine quality—would lose their value when carried out (a hint of James Hilton’s Lost Horizon). Finer diamonds, virtually since their original discovery, have been restricted from travel.

The Diamantes exhibit does not soft-shoe past this aspect of the industry. The 10-carat Eureka Diamond (cut from its original size of 22 carats), discovered in South Africa in 1867 by a latter-day Archimedes named Jacob Erasmus, heralded the era of extensive diamond mining. The Kimberley mine, where young Jacob made his discovery, has intrigue in equal measure to its abundance. Photos of the original mines, the intricate rope and pulley systems necessitated by the ardour with which individual and relatively tiny claims were protected (to set one foot on another ‘s claim site was considered grounds for execution), and the general danger to all workers are prominent in the exhibit, a component of the vast canvas being painted. Cecil Rhodes, creator of the De Beers Company and founder of Rhodesia (now divided into Zambia and Zimbabwe), is a central figure, and his story is included here.

The most obvious result of the Kimberley find was wider availability for diamonds. The quality might vary, but quantity was no longer a serious issue; virtually anyone with a certain amount of cash could have a diamond, something that had not been true for many centuries.

Another seminal event was the French government’s selling of the Crown Jewels; for that country an important symbolic act, but for others, especially wealthy American industrialists, the prime moment for opulent consumption. They were opulent and they consumed; many of the most coveted objects, previously unattainable at any price, were purchased on the open market. Thus, many of the treasures on display in Quebec City travelled not from Europe, but from New York and Chicago.

It illuminates what a great feat the Musée has accomplished to know that many of these pieces are from private collections, though some have permanent homes in special exhibits in such places as the Museum of Natural History. It explains also why this is a rotating exhibit: you will always see fabulous pieces, but many are here for one-third or one-half of the run, to be replaced by equally fabulous treasures.

François Tremblay is Director of International Exhibitions at the Musée. When asked over a premier plat at Chez Bernard how difficult it was to bring the exhibit to Quebec City, he looked into the expansive cupola arching over the main dining room as if checking to see if God was still with him. “It was very good fortune, a lot of planning and execution, but it was, most important, about relationships and a shared vision.”

That other museums and private owners were involved goes without saying. But it takes only a little imagination to realize that where priceless, one of a kind pieces, each defining the word “irreplaceable” are concerned, there has to be a strong rationale for moving them from their permanent homes. There also has to be a core group of committed pieces, which serve as lodestone for others; to attract the best, you need the best.

17th century Dutch pendant, from St. Willibrordus Church, Antwerp.

M. Tremblay is understated, but acknowledges with a slight smile that bringing this exhibit to the Musée required four years of concentrated effort: “Not everyone believed we could have so many wonderful pieces in one place at one time. And there had to be a rotation, as many pieces are, by policy, allowed out for a maximum period, often three months, sometimes six, but very rarely more than that.” The key: “I have many friends in similar jobs to mine around the world, and with enough time it is sometimes possible to put such a thing as this together. And when it is done, we can all be proud that this is in our Musée.”

The fuss about diamonds in general, and certainly about these displayed objects, is not really subjective. The famous four ‘Cs’ of colour, clarity, cut and carat (weight) all are considered in establishing value. Brilliance (returned light) and fire (the play of colours from light dispersion within the stone) are important. “Fancy colours” or richly coloured diamonds may be valued if they are fully afire. Further, a system of colour grading, from “D” (colourless, and the extreme of value) to “Z” (yellow, and the nether end of the value scale for gem quality diamonds) provides an industry standard for appraisal.

This is all fine, and points out the necessity of trusting your jeweller, with whom you should have a fairly rigorous screening session before plonking down for that engagement ring. The cus