Thandiwe Muriu’s Photography Is an Exploration of Female Power Through Optical Illusion

Feminine mystique.

“Don’t let anyone or anything dictate for you, including culture,” says Thandiwe Muriu.

Introduced to photography as a young girl, Muriu was encouraged by her father to explore countercultural avenues of expression that are often less accessible to women. She became a successful commercial photographer, creating compelling campaigns for fashion, lifestyle, and spirits companies.

But it is her series of portraits that have gained her the most recognition. In CAMO, which began several years ago and marked her debut in the fine art world, she captures her experience as an African woman through photographs that appear psychedelic, almost dizzying in their intricate details. This series is Muriu’s vision of what liberated beauty looks like and challenges Kenya’s societal beauty constructs.

“There are many unspoken things about beauty, and I think this applies across cultures,” she says. “The joy of the CAMO series appears playful and fun, but these images were constructed on the idea that we should look a certain way to be seen as beautiful. That concept applies to women around the world.”

Her artistic process begins by selecting kitenge fabrics that are traditionally worn for special events. Without using any digital manipulation, she manipulates them into more contemporary garments whose patterns range from aggressive to whimsical, a reminder of the many facets of a woman’s personality.

Through her own research, Muriu gained insight to Kenya’s cultural traditions and was compelled to honour practices she previously thought were outdated. Hair has proven to be one of the most challenging aspects of this project. “Hair has been one of those things we have rejected in our quest for modernization, and yet we had such a rich, beautiful hair culture from 50 to 100 years ago,” she says.

Challenging beauty standards has become a tenet of the artist’s work. This can be seen in the models’ elaborate braided hairstyles and their proudly gapped teeth. “I come from the largest tribe in Kenya, called the Kikuyu, and a woman with a gap in her teeth is deemed more beautiful than those without,” Muriu says. “Many of my friends who have gaps go and get braces to close them because in modern times it is not a sign of beauty. I want to represent what was once considered so beautiful.”

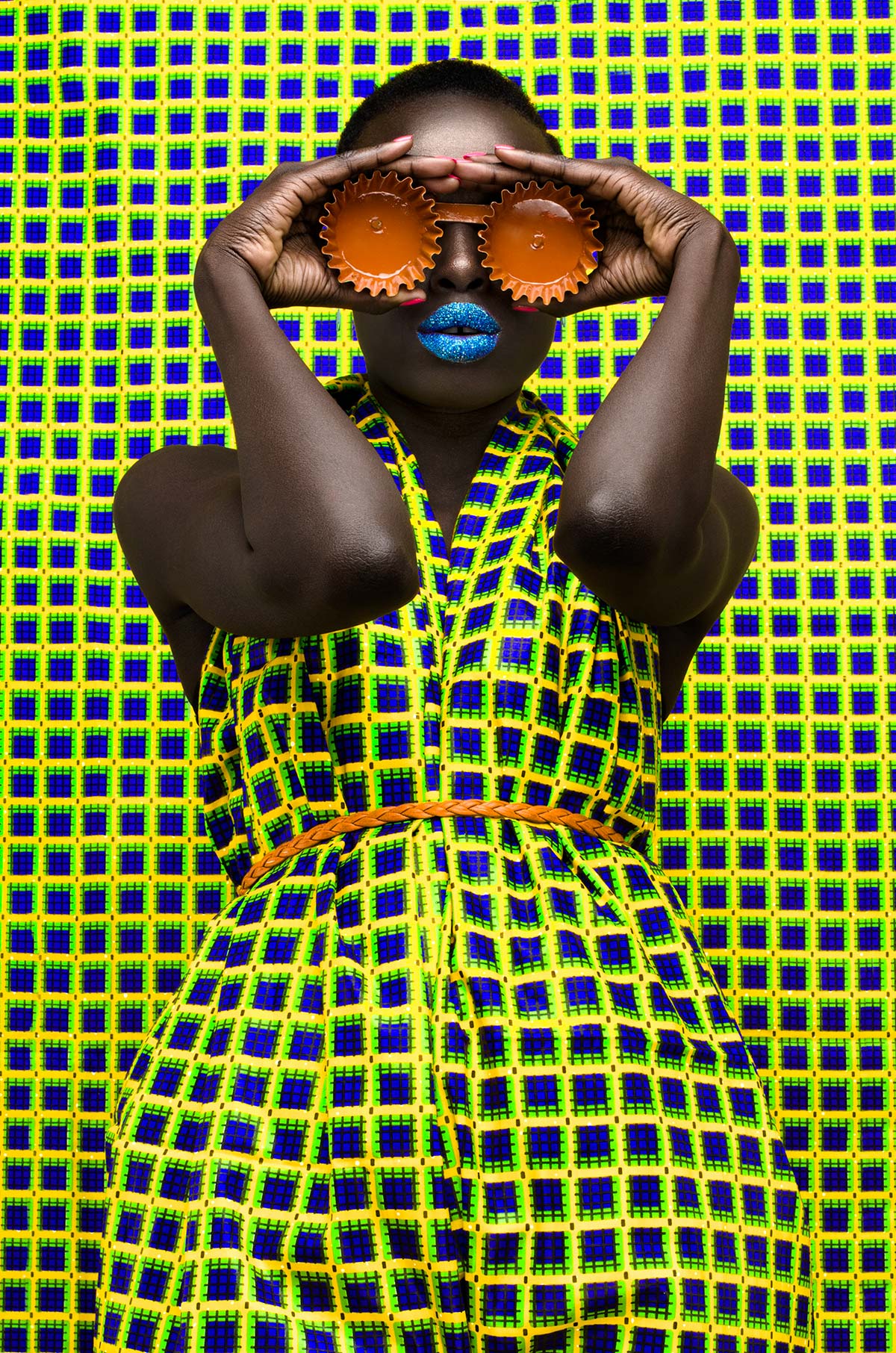

CAMO’s images also feature unexpected objects throughout, to explore Kenyan peoples’ abilities to repurpose everyday items. “Kenyans use things beyond their intended purpose because there is a lack of resources,” Muriu says. “These are objects you would never think to put on a person, and yet they become these eye-catching accessories. I think people are like this. For example, the things you don’t like about yourself are actually the things that give you incredible beauty, both physically and through personality.”

Muriu’s reimagined beauty standards point to a clear, multifaceted, image. A woman that is liberated. A woman that chooses. A woman that honours her beauty and her power.

With CAMO, Muriu is anything but hidden.

These three images were inspired by Muriu’s mother—the first person to teach her about beauty.

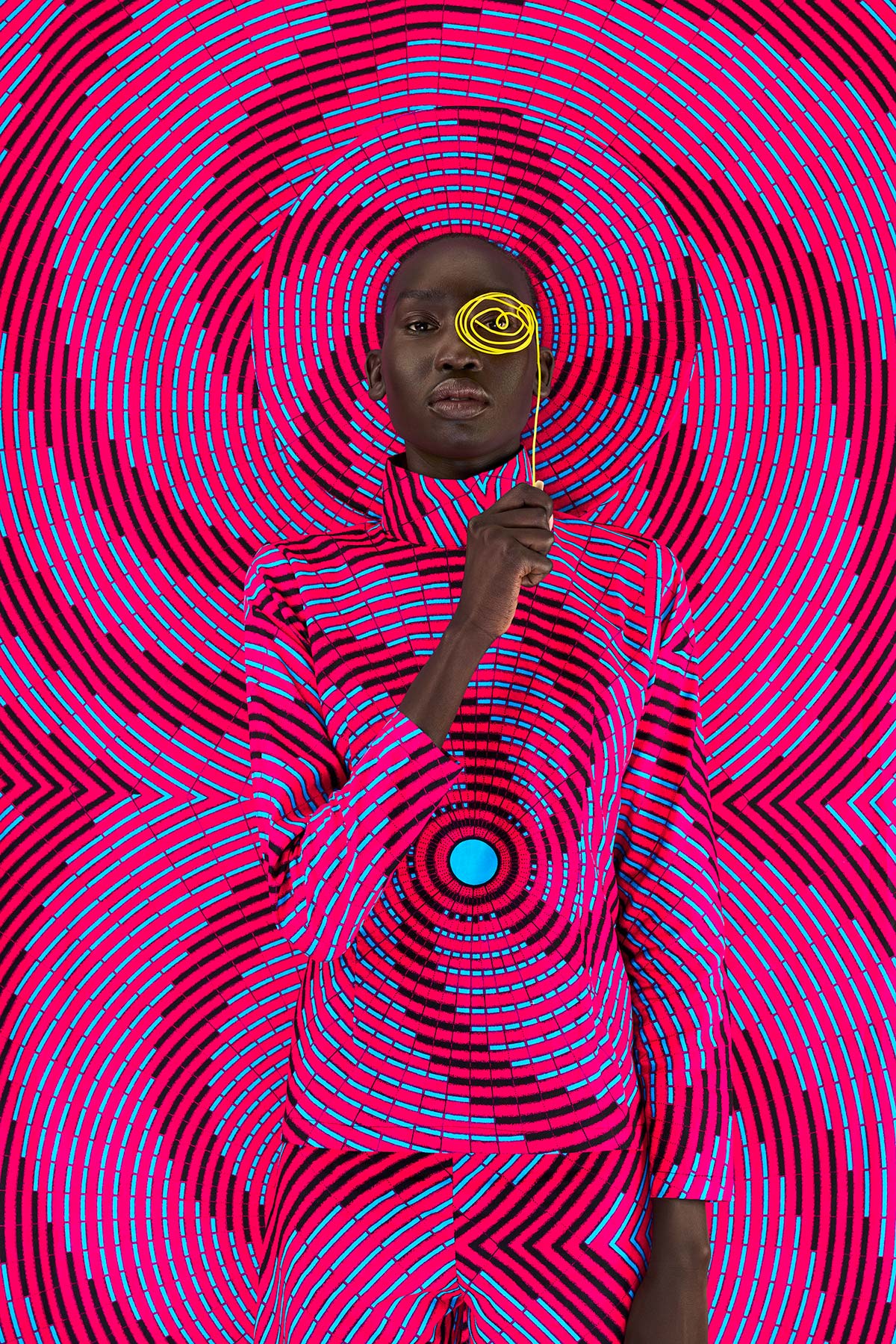

Camo 5

Muriu drew upon a memory from her youth, where the smell of her mother’s baking drew her and her siblings to the kitchen, eager to taste the sweets being prepared for guests. “This is the smell of a mother’s love and the joy of her cooking,” says Muriu.

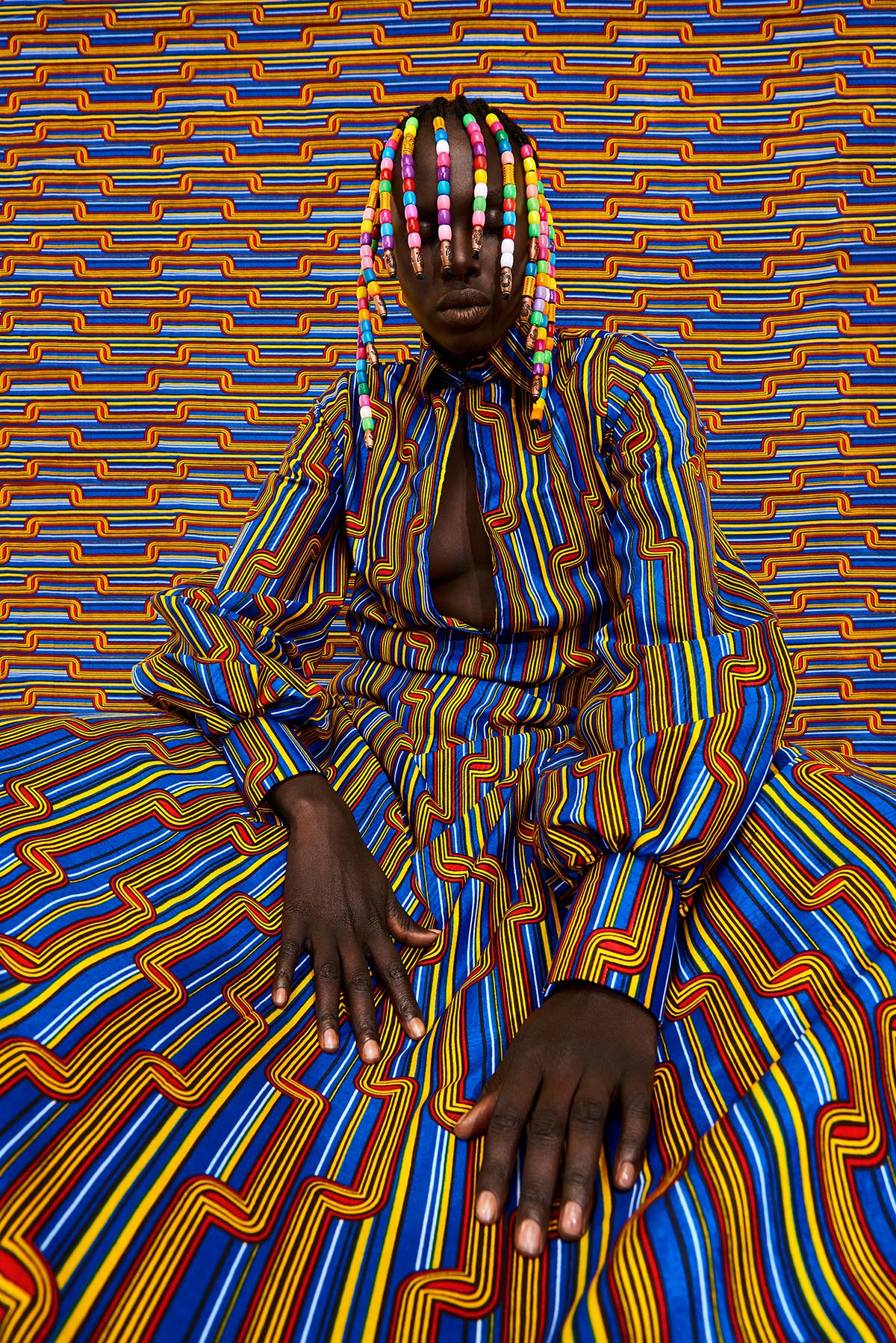

Camo 2.0 4415

As a child, Muriu often had her hair done with large colorful beads that clicked and danced around her face. This is when she felt the most beautiful. Across Africa, these beads can symbolize age and status and have recently made a resurgence, especially in Nairobi, where women weave them into elaborate up-do’s. In this image, the model exemplifies the godliness that can be channeled through personal standards of beauty.

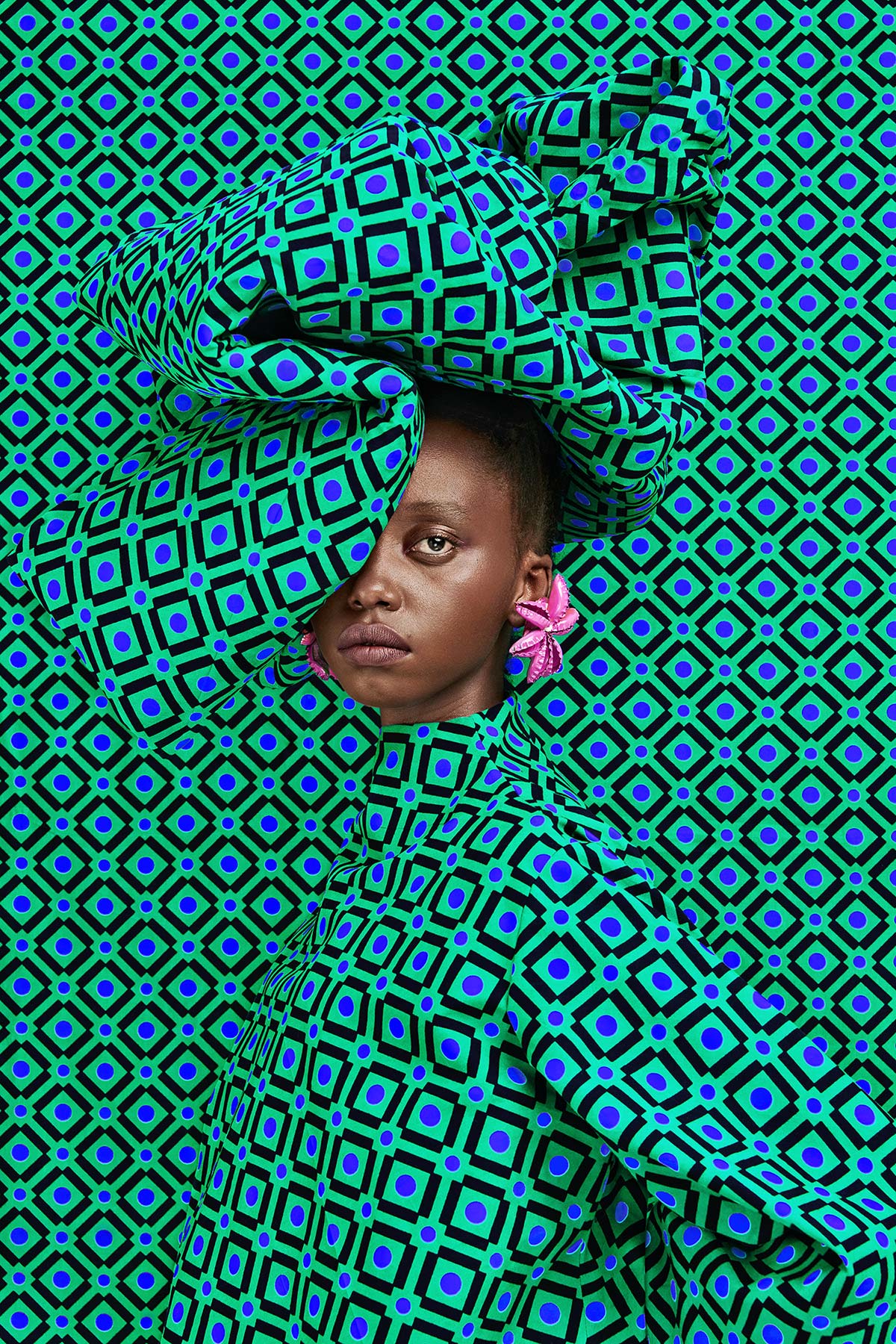

Camo 36

A modern interpretation of the head wraps that Muriu’s mother wears each day is paired with hot-pink bottle cap earrings here. This process of wrapping and knotting the fabric represents the act of crowning oneself. “Everyday, women are creating these unique works of art that can never be replicated again,” says Muriu.