Responding to Needs with Elegance: An Interview with Diébédo Francis Kéré

Breezy design.

A lack of reliable infrastructure can be detrimental to the health of communities. While international efforts and charitable organizations are committed to helping countries in need, the specific needs of the community can be outsized by the desire for efficiency and a top-down approach.

Diébédo Francis Kéré is a testament to building from the ground up. His is more than an aspirational story, it’s an ongoing commentary on the potentials for continuity, sustainability, and the health of communities. Born 1965 in Gando, Burkina Faso, to a community leader, he was sent away to school and eventually worked his way into the Technical University of Berlin. But soon he was back in Gando, taking his new found expertise with him.

“I started out my career as an architect with the desire to build a school for my people that would result in little maintenance and result in few running costs,” he says. What started out as a way to give back to his community soon turned into an international phenomenon. With the support of his community and the design world, Kéré efforts redoubled. “I continued with the teacher’s housing and plans for a library and I continue to work in this manner of taking one step at a time to this day.”

Of course, working in more remote areas or ones that have seen economic hardship poses some obstacles. Kéré emphasizes the need to see opportunity in problems that others may be paralyzed by. “I believe facing and solving a given adversity is often the mother of innovation and can be a great teacher,” he say. “It certainly is one that has taught me many things.”

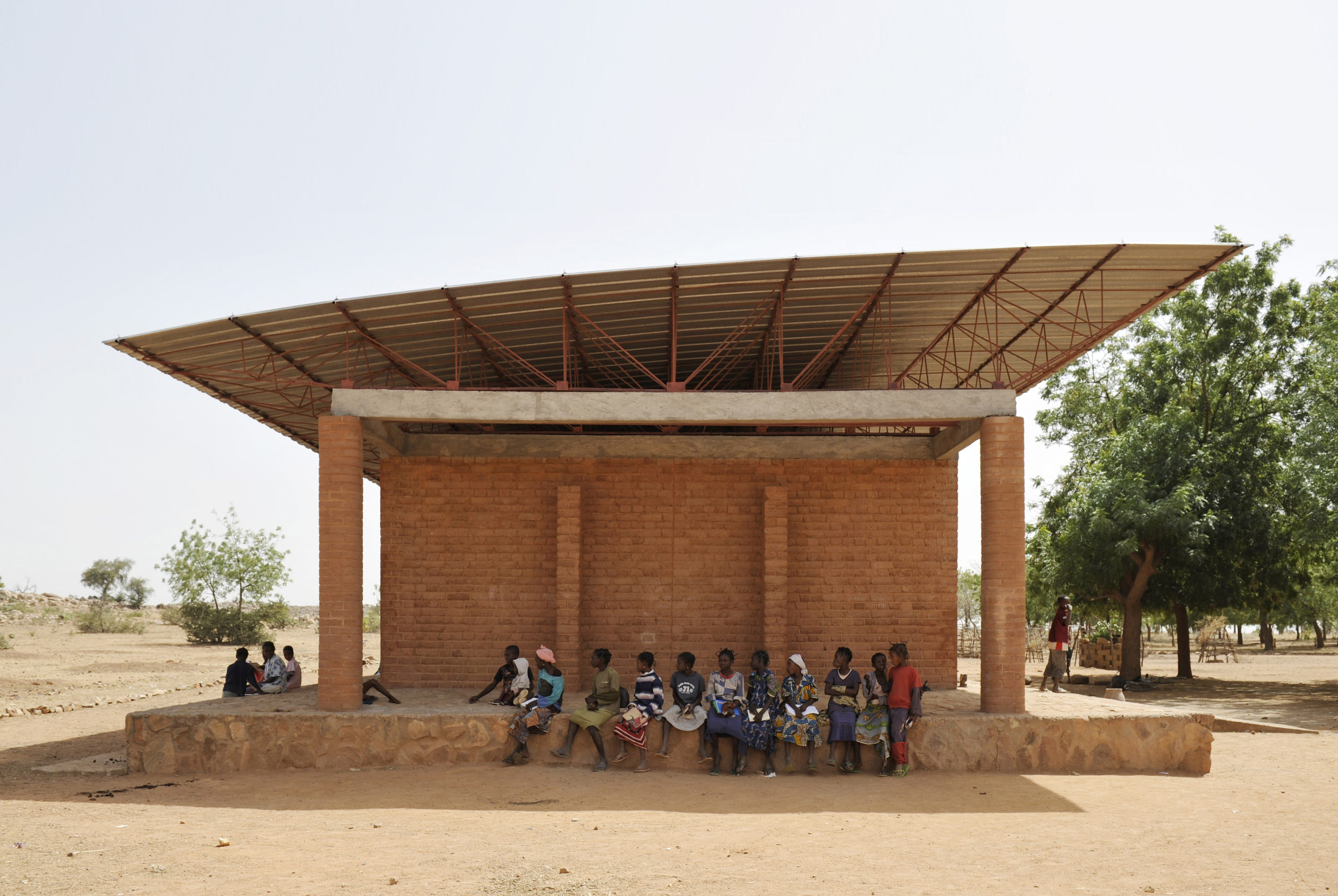

The Gando Primary school. Photo by Erik-Jan Ouwerkerk.

Problems often carry, in their core, their own solution. In building the Gando primary school, Kéré used the strengths of the land—like the clay—to construct a building that would be suited to the hot environment. Windows and perforation in the material allow for the dry air to circulate and lessen the energy usage associated with many contemporary buildings.

Kéré’s approach to sustainable building is incredibly pragmatic: “How can I become more mindful in my use of material? And how can I contribute within my chosen profession to improving the situation? These were guiding questions for me and I think are the very core of what my peers and those related to our field should ask themselves. For it is us as creators of the environment we live in that can greatly influence how sustainable any project we design is.”

Driven by urgent contemporary questions, his many projects and engagements are tied together by an elegant style that takes cues from trees and dunes, and most feature spaces that rotate around open space to promote social activity. Projects from the National Park of Mali to the Beijing Pavilion feature the lofty geometry and suspension that makes the Gando School so remarkable.

Surgical Clinic and Health Center in Léo. Photo by Andrea Maretto for Kéré Architecture.

It seems Kéré and his foundation work from a position of response: they see a need and act to reimagine standards of design based on these needs. Of course, in order to respond, one must ask the right questions. “How does one act and react in light of ever diminishing resources, global warming, and environmental pollution?” asks Kéré. “And this without compromising on design?” What results from these questions are models which are repeatable yet individualizable but that do not sacrifice inspiration or grandeur.

The community-based method is durable, and has results that go beyond the formal aesthetics, in that the buildings Kéré works on are usually civic. Structures become even more stable when they are building up social infrastructure; education and quorum make communities stronger.

But what about urban spaces? Or spaces with more fractious social structures like multi-cultural cities? These questions arise when one thinks about Kere’s proposed plans for the Burkina Faso National Assembly. Its is a beautiful and idiosyncratic design that recalls the hope of social architects at the height of modernism, with sloping roofs that mimic dunes, culminating in a pyramid like structure that will feature community gardens. Of course, the façade of the building is perforated and works as a sort of canopy over a large courtyard the proceeds the building proper.

Burkina Faso National Assembly rendering.

“Now the challenge, always, is to adapt [my methods] to the given situation and it can take many forms as no one community is the same, nor is it always clear who the community is for a given project,” he says about the challenges of building the National Assembly. The building could usher in a new era of regional urbanity in design. “Seeing my method and approach find a place in so many corners of this world means we are doing something right as sustainable methods, the use of locally abundant material and alternative voices are coming to the fore.”

Kéré will be a keynote speaker at IDS Toronto Friday January 17th 10 AM.

_________

Never miss a story. Sign up for NUVO’s weekly newsletter here.