Wave Energy: The Perfect Carbon-Free Companion to Solar?

An enticing solution.

As we rush headlong toward a future powered by 100 per cent renewable energy, governments, businesses, and individuals are scrambling to pack roofs with solar panels, fields with wind turbines, and rivers with hydro plants. The world collectively invested 755 billion dollars in renewables in 2021, shattering previous records.

But even with investment and public support at all-time highs, it will be nearly impossible to completely phase out fossil fuels without massive utility-scale battery storage, either in the form of rare earth metals like lithium and cobalt—whose procurement requires environmentally dubious mining practices—or massive water batteries, which have their own host of controversies. The problem is simple: solar only works during the day, and the wind can be unpredictable. How do we fill the intervening time without fossil fuels?

A nascent renewable technology called wave energy provides an enticing solution. When the sun goes down or the wind stops blowing, coastal communities could rely on the constant movement of the ocean to power their cities. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, wave power has a theoretical annual energy potential of 2.64 trillion kilowatt hours, or 66 per cent of total U.S. electricity needs in 2020.

Wave energy is projected to be a $141.1 million industry by 2027, representing annual growth of 17.8 per cent from 2020. This represents a tiny fraction of the investment in mature technologies like solar and wind, but for Balky Nair, president of Seattle-based Oscilla Power, wave energy is just getting started.

“Fundamentally, the issue with wave energy is that the technology is young. It took awhile for the technology to be good enough that the cost of energy was reasonable,” he says. “You can, at scale, get to costs that are competitive, especially compared with storage. In the next five years, it will be in a growth stage, but in 10 years I believe it can get to the point where it’s starting to make an impact on the grid.”

Even before wave energy becomes cost-competitive with solar and wind, Nair believes it has applications in coastal communities and niche markets, such as island nations or off-shore data centres. Oscilla Power hopes to deploy its 100-kilowatt Triton-C device to remote and isolated communities that struggle with energy independence.

“There are some pretty small coastal communities where having 100 kilowatts of power available is what they need,” Nair explains. “So there’s a capital cost associated with getting it installed, but then they eliminate the cost of having to ship diesel on a regular basis. Especially at a time like now, when oil prices are spiking, the cost of electricity can be prohibitively high.”

By the numbers, wave power has undeniable advantages over more mature renewables. Because water is 850 times denser than air, it possesses 1,000 times the kinetic energy of wind power. Wave energy also requires 0.5 per cent of the land area that wind does. Beyond this, wave energy has the potential to sidestep a perennial obstacle to meaningful environmental change: NIMBYism.

The Not In My Backyard movement has derailed numerous laudable projects, from affordable housing to bicycling infrastructure and renewable energy. Concerns over property values and sightlines tend to outweigh investment in equitable ventures, especially in high-income neighbourhoods. According to Nair, wave power evades this issue altogether.

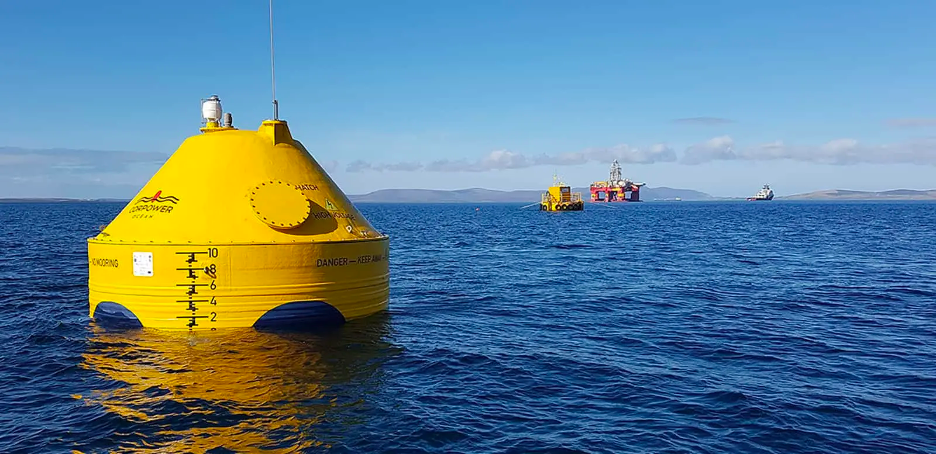

“The sort of people who are complaining about offshore wind—homeowners near the coast and so on—that issue will be eliminated,” he says. “The issue of being a problem with the visual profile—that will be eliminated simply because you can’t see these devices from shore.”

As power generators bob inconspicuously near the ocean’s surface, coastal communities can enjoy unobstructed views and depend on a decentralized microgrid pumping clean energy continuously through all seasons and varied weather. Wave energy’s ascension might be virtually imperceptible to the average person, but in the coming years, our coasts may begin to fill with unimposing buoys that make our carbon-free aspirations a reality.