Blown Away’s Alexander Rosenberg on His Conceptual Glass Practice

Synthetized craft.

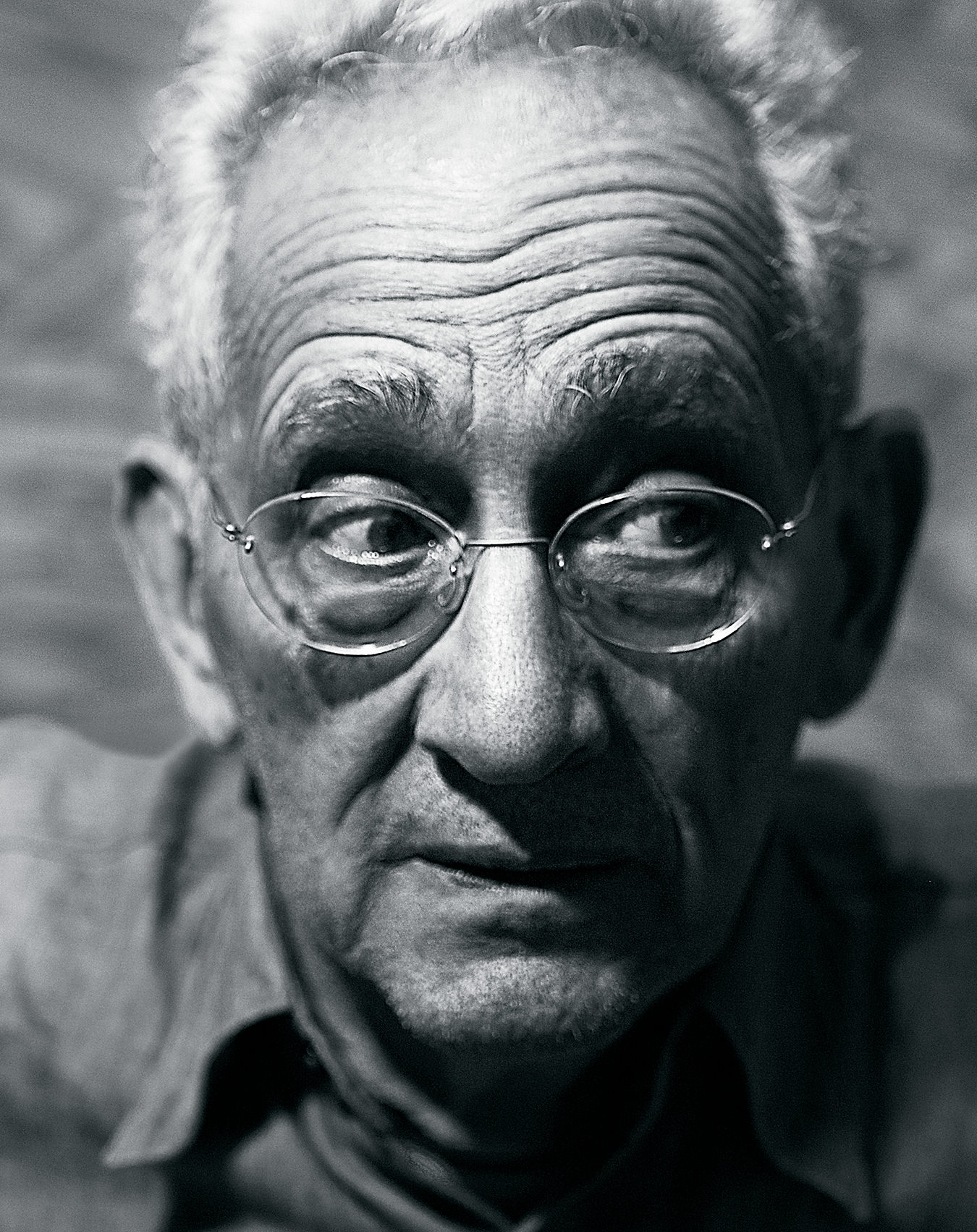

Artist Alexander Rosenberg. <i>Credit: Carola Rummens</i>

Airing initially in Canada, Netflix’s reality competition, Blown Away, has introduced audiences to the intricacies and allures of glass-blowing and its techniques and styles—but it also changed the life of Philadephia artist Alexander Rosenberg.

Rosenberg in the studio; Credit: David Leyes.

“I didn’t even get first place,” Rosenberg jokes, but soon after he placed third on the show, the requests for work started steadily flowing in, due perhaps to his laid-back attitude, intelligence, and commitment to mining the history of the form and genre for deeper connections and stories. This attention to the philosophy and historical detail of glass sets Rosenberg apart from artists who, while more experienced technically, rely on graphic power and awe. Rosenberg’s approach is more subtle.

“Glass is archaic and high tech at the same time,” Rosenberg says. “It’s ancient. Thousands of years old. And hasn’t even really changed that much. And it’s the same material in the screens of all our devices or, like, fibre optic cables.”

The Disappointment of the Tropics, 2018.

The importance and possibilities of glass, an early plastic form ubiquitous throughout history, in medical equipment, skyscrapers, and countless other things, did not dawn on Rosenberg until he was living with a friend who was taking a glass-blowing course. At first, he says, he thought of glass-blowing as more like a sport, set apart from the traditional fine arts in which he was training—but he soon became enamoured with it on a deeper level.

There is a sort of absence that happens with glass, he believes: “It’s unusual to be able to see the inside and outside of something at the same time.” Glass also attended almost every scientific discovery since the Enlightenment: a mixture of poetry and functionality that appeals to Rosenberg, who, viewers of the show will remember, often strayed into the realm of historical and scientific objects like beakers and containers for exotic plants. Rosenberg’s preference for exploring glass’ possibilities for modulating light rather than straying into a heavy use of colour gives his work an elegance appropriate for both the art gallery and the historical or interior design collector—putting him somewhere between mad scientist and aesthete.

Pretium Certum Constitutum, 2016.

As for the show, Rosenberg was pleasantly surprised by the honesty of its production and the positive aftermath. “Everybody’s always offering to pay you, and exposure, and it’s like: Oh, exposure is not really worth very much. It doesn’t pay my mortgage. It doesn’t. It turns out Netflix exposure is actually, you know, worthwhile,” he tells me.

His success on the show has propelled his social media following, which has in turn led to plenty of commissions, which he sometimes works on with the aid of his students at Salem Community College in southern New Jersey.

Lighting Prototype for Late Anthropocene.

Rosenberg has also been able to focus more on issues of climate change, waste, and obsolete objects caught between overlapping historical periods. He notes that if natural materials become scarce and hard to come by, we will still have a surplus of electronic waste.

He continues working on these themes as part of Philadephia’s Recycled Artist in Residency program (RAIR). Even aesthetic design should, he asserts, accommodate both innovation and collapse.

Reliquary, or From Beneath a Piano Keyboard Used For 103 Years, 2013.

In addition to this work and his teaching, Rosenberg has an ongoing exhibition at the Eastern State Penitentiary Historic Site. “I’m really slowly accepting that this is maybe, you know, stable,” he says of his burgeoning practice, and it is inspiring to see him use his new-found fame to contribute to important conversations around the evolution of consumer and scientific goods as well as the exigent questions about use in the Anthropocene.