The Canadian Boy Who Became the Great Farini

A life on the wire.

In 1859, at the foot of Walton Street in Port Hope, Ontario, a local boy named William Hunt walked a tightrope over the Ganaraska River. Just a few months later, he was calling himself Farini, after an obscure Italian revolutionary, and he soon became the second man in history to cross Niagara Falls on a rope. The Ganaraska walk marked the public beginning of a long, strange life; a life so full of adventure, tragedy, achievement, and mystery that it might give pause to the gullible. But pause is one of the few things Farini never did.

I first heard of him from Daniel Mannix, historian and ex-carnie. For many years, Mannix had been the world’s champion sword-swallower, and he knew everything about sideshows and “freaks” (not a pejorative). Mannix described Farini as a former ropewalker and acrobat who had performed amazing acts in venues around the world. Mannix said Farini had been a mysterious figure with a dark past.

He didn’t know the half of it.

William Hunt was born in June 1838, and grew up in Southern Ontario near Port Hope. At an early age, Willie became entranced by the circus and yearned to be a performer. To this end, he began a regimen of exercise and acrobatics. He worked out with weight scales and climbed the sides of the family barn using pegs he’d drilled into the walls. Soon he was showing off at town fairs. One morning, he strung a rope from a stake in the ground to the loft of the barn and walked all the way on his third attempt. A couple of months later he was walking across the Ganaraska.

As the Great Farini, he joined the famous Dan Rice circus—Rice was the clown who became a confidant of President Lincoln, and was in fact the man upon whom Uncle Sam is modelled—but quit to roam the Wild West, where he got into all sorts of scrapes. In the summer of 1860, he was at Niagara Falls to challenge the great Blondin, the first man to cross the falls on a rope.

Farini successfully completed not only this first walk but also many others over the summer. His goal seemed not only to outdo Blondin, but to test the limits of daring. Blondin’s act was based on making it all appear effortless; Farini drew crowds with the allure of disaster. “It can’t be done!” was the usual comment before each of his exploits. Farini would get to the middle of the walk and perform acrobatic feats, often hanging upside-down over the raging tumult, gripping the rope with his insteps.

Walking a rope over Niagara Falls is a tough act to follow but Farini did it by crossing the gorge and the river on a pair of stilts. Later, a crowd of 15,000 saw him walk along a wire strung 37 metres above Chaudière Falls near Ottawa. According to Shane Peacock, author of a marvelous biography of the man, the hottest topic whenever Farini was mentioned was how he was going to die.

He toured the world and, along with the rope walking, gave exhibitions of strength and gymnastics. He was also a gifted mechanic, and from his youth had been interested in creating new gadgets and machinery.

Newspaper reporters often made mention of the number of females in the audiences of the handsome and well-muscled Farini. There were rumours of several marriages, and there were actual marriages during his youth, but these remain shrouded in mystery.

In 1862, Farini abruptly quit show business to join the Union Army in the War Between the States. He was employed by General McClellan to devise quick and efficient ways of crossing creeks and rivers.

McClellan later used him on intelligence missions. But when President Lincoln removed the General after the disastrous loss of life at Antietam, Farini left the Union Army and went to Havana, Cuba, with his wife, a Hope township girl named Mary Osbourne.

Farini was a man to whom legends attached; handsome, dashing, vigorous, he had seemingly been everywhere.

He had been training Mary to hold on to his back while he walked the rope. In Havana, Farini accomplished four solo crossings of the Plaza de Toros in front of a crowd of 30,000. He started a fifth, carrying Mary. When they were almost at the end, Mary suddenly removed one arm from around her husband’s neck to wave to the wildly cheering crowd. In rope walking, any spontaneous move can mean tragedy, and Mary fell. Then, in what may be the most incredible move in the entire history of tightrope walking, Farini caught his wife, clutching her dress with one hand. He lowered himself until he had hooked the backs of his knees over the rope. But before he could pull her up, the dress ripped and Mary fell to her death.

Incredibly, Farini was soon on the wire again. But after a few shows, lonely and distraught, he disappeared into South America. After six months of wandering the continent, he emerged in Europe doing a wire and trapeze act. In the late 1860s, he began training and travelling with a 10-year-old boy whom he advertised as his son, or “El Niño”. Where he found him—whether on the street, in an orphanage, or elsewhere—has never been determined.

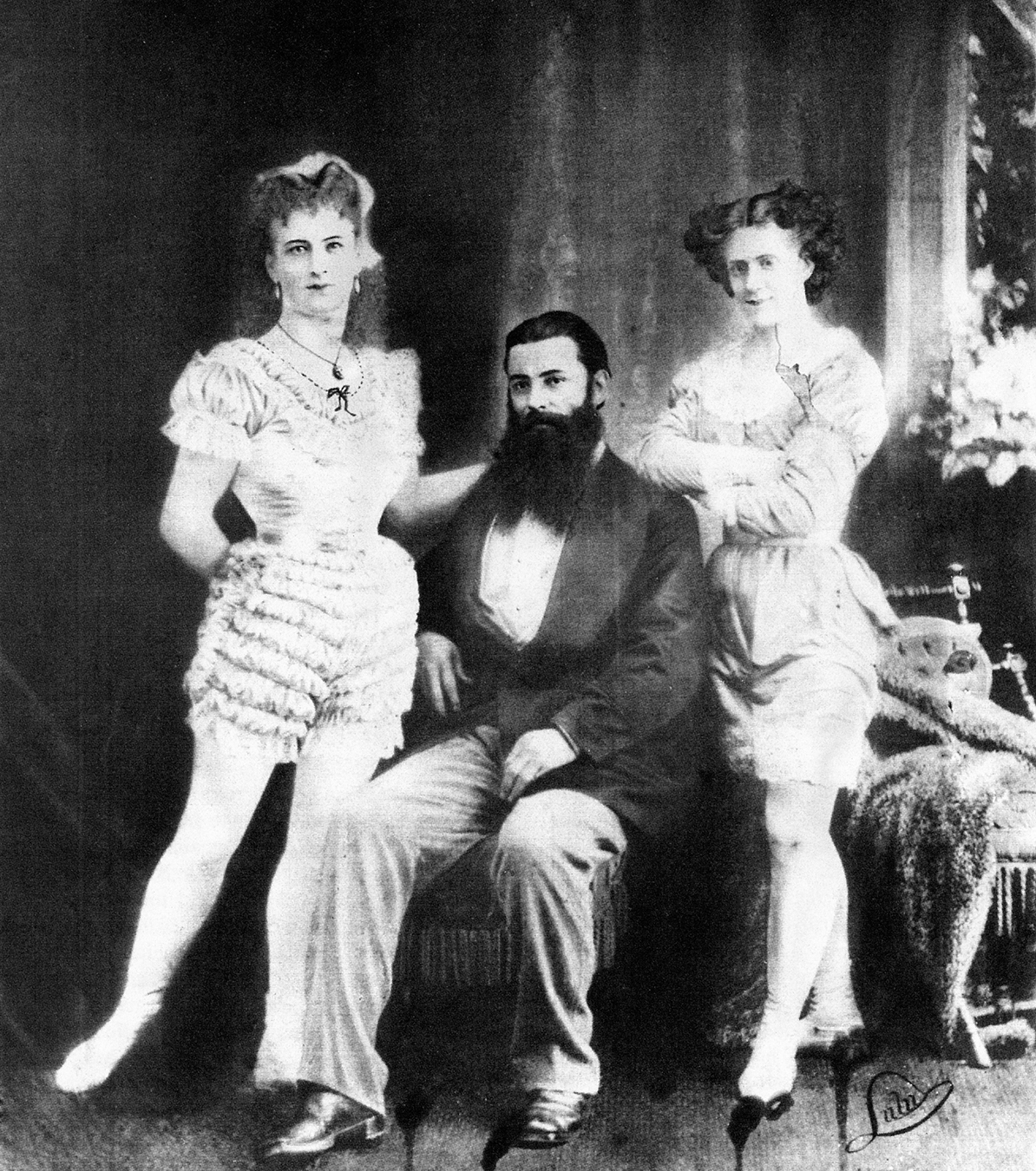

After a couple of seasons, Farini debuted what he declared was a sensational new act: the glorious, high-flying Lulu, who soon became a sensation in Europe and the Americas. By all newspaper accounts Lulu was beautiful, with long, wavy blond hair, and she garnered dozens of marriage proposals. Lulu was actually “El Niño” in drag. When Lulu was no longer able to pass, he presented himself as Lu, doing his act in female trapeze artist garb but with hair shorn and parted, and his moustache waxed.

By the time he reached his 30s, Farini’s own career as a tightrope walker and trapeze artist was over. He devoted himself to training and promoting new acts and roaming the world in search of human and animal oddities. He originated the human cannonball act. But perhaps his greatest sensation was Krao, the Missing Link. Farini claimed to have found her in Siam, and perhaps he did. Doctors and scientists examined Krao and admitted they didn’t know what she was.

In 1885, Farini again quit show business, and with Lu (by now a bearded photographer) he disappeared into southern Africa, where they spent several months exploring the Kalahari Desert. In his book about the region, published the following year, Farini claimed to have found the remains of a vanished civilization. Explorers have been looking for his Lost City of the Kalahari ever since.

The African trip just added to his legend. He was a man to whom legends attached. Handsome, dashing, vigorous, he had seemingly been everywhere, spoke seven languages, and was as liable to be found in the company of a pinhead and a tattooed lady as with dukes and earls.

After returning to Europe, Farini continued to book circus and music hall acts, but by the late-1880s he was spending most of his time on his inventions and a new enthusiasm: growing begonias. (He eventually wrote a book about the flowers.) He also patented many inventions, including the modern parachute and folding theatre seats. Back in Canada in the late-1890s, Farini backed and co-invented, with Frederick Knapp, a huge roller boat that, it was claimed, would make the crossing to Europe in two days. It only barely got out of Toronto harbour and is now landfill under the Gardiner Expressway.

In his 60s, Farini took up painting. In 1911, he went to Europe with his German-born wife, Anna, and was caught in Germany when the First World War broke out. He spent his time painting, keeping a detailed diary, and translating war accounts from German publications.

After the war, he returned to Port Hope with Anna. They existed on his wife’s small inheritance and on the sales of parcels of Farini’s land holdings. In his 80s, Farini on his bicycle was a familiar sight on the streets of the small town and on dirt roads in the country. He would pedal 10 kilometres to a relative’s farm and pitch in with the chores; he is remembered vaulting onto wagons with the agility of an athletic teenager. The rest of his time was spent painting.

The brooding young man with an arrogant demeanour and a Svengali-like presence had mellowed into a kindly old artist and storyteller. Not that the older citizens believed his tales of duels and gunfights, of pygmies and lost cities, of the applause of thousands. Little kids did, however, and they followed him along the sidewalks calling, “Freeny, Freeny!”

In 1929, at an age and in a manner that those early commentators would never have predicted, the Great Farini died, at 90, of the flu.

Nowadays in Port Hope, you can walk along the river that he crossed 150 years ago to a restaurant named after him, have a “Farini schnitzel”, and toast his extravagant memory.

Photo by Ron Roels, ©The Niagara Falls (Ontario) Public Library.