Cave Explores Ideas of “Good” Design in Vancouver

In 1969, the influential art critic and collector Clement Greenberg declared, “I deplore the tendency to over-value art.” The statement was notable given that the controversial writer had spent some three decades explicitly and emphatically defining exactly what kind of art is worthy of being considered capital A Art.

It’s been theorized that Greenberg was referring to his own tendencies to tarry in absolutes. His view of art was often devoid of pleasure, due to what were, in his eyes, art’s many pitfalls. As art historian Donald Kuspit suggests, “If his writings are any clue, much of [art] made him unhappy, for it didn’t live up to his aesthetic expectations.”

Curiosity, pleasure, appreciation–this is how to shake loose the prohibitive, outdated classifications (yeah, Greenbergian) of high and low, good and bad that persist. Vancouver’s Cave exercises this philosophy, bringing together a curated showroom of design objects and art that values character over ideology.

Opened in 2019, the by-appointment gallery space is an accumulation of design objects, furniture, art, textiles, rocks, lighting collected by Max King.

“Growing up in the mountains [in British Columbia], my mom was a potter and we had a studio in the home, there was always this creative language that existed in the house–one of craft, the idea of building with your hands,” reflects King over video call. “Then, within that framework, something that has function. Innately, I’m attracted to that.”

That allure is visible in the kinds of pieces presented at Cave. Items like Italian designer Joe Colombo’s 5 in 1 by Progetti: a cognac glass; a white wine glass; a red wine glass; a water glass; and a grappa glass that stack into a single sculpture. A sky blue 1950s production of Alvar Aalto’s 330S iconic pendant light. A 1980s painting of pop chanteuse Sade, artist unknown, from a flea market in Yokohama. Within the galley’s semi-domestic space, Cave is more of a show-and-tell experience.

Many of these pieces, on sale through Cave, are featured in King’s collaboration with Inform Interiors in the windows exhibition, Patina (on through March 31st). An extension of the gallery, the installation brings together King’s selections, new pieces from Inform, borrowed pieces from friends, and items from Inform’s Nancy Bendtsen’s personal collection.

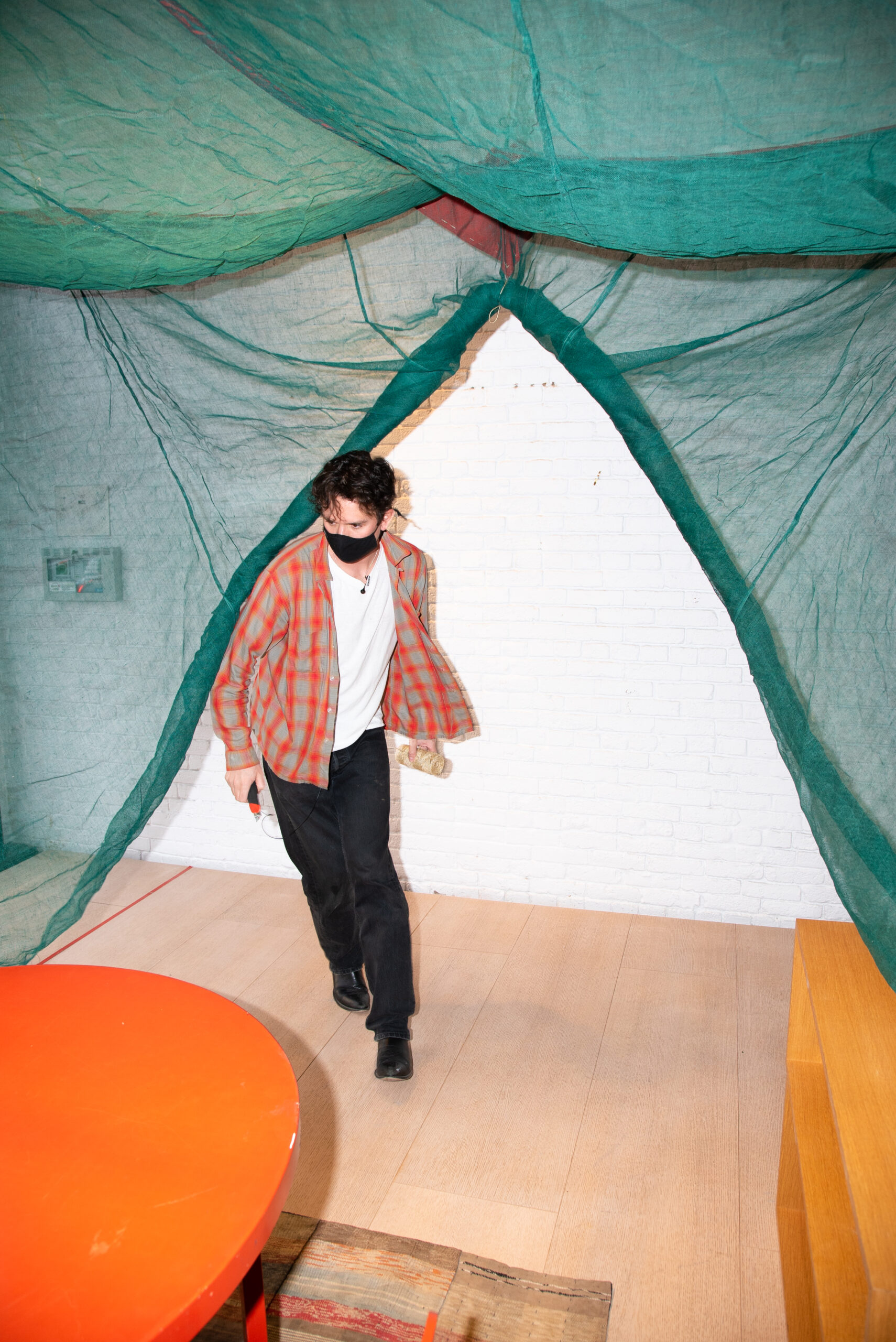

In the window, a Japanese Kaya mosquito net, made from hemp and dyed indigo, enwraps a lovingly worn Alvar Aalto dining set. “To me, patina is the visual history of experience,” King says. “It really only works if the design is timeless enough to live long enough to receive patina–we’re really celebrating classic design.”

King is a self-taught design buff, his impressive knowledge gleaned over time at the now-shuttered Inventory magazine and through his current role at streetwear brand, Stüssy, which finds him travelling often for inspiration. This slightly left-field position grants King the advantage of an outsider perspective. “Working in retail, working in fashion, you’re always trying to build value,” says King. “Art is whatever strikes you or makes you feel good. I think that people often get obsessed with the validation that comes with a name and I really wanted to break down that hierarchy.”

Cave’s exclusive collaboration with Brooklyn’s Green River Project furthers this focus on an expanded field of art. Stiff-backed and made from reclaimed hardwood from Vancouver Island, the interventions are minimal, with nods to modern design and Shaker practicality. Its interest is the perspective of nature and the designer’s relationship to time.

“Don’t even get me started on rocks,” laughs King, reaching for a prized stone, remarkably smooth and curvaceous. “I have a close interest in Isamu Noguchi, Jean Arp, Henry Moore– biomorphic shapes.” It’s a fitting fixation as King reserves the highest praise for those who share in his belief in nature as the primary, uncredited artist. King recalls a trip he took to Henry Moore’s former home outside of London, “You can walk through his house. After he died they had left it just as he had lived,” he says. “On a display shelf there were all these bones and found rocks, and next to it a maquette from Alexander Calder.”

In 1947, Greenberg wrote his infamously scathing critique of Moore’s retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art, a lone dissenting opinion. Not abstract enough, too timid, monotonous, not from New York.

“Above Moore’s kitchen stove there was this painting, covered in oil and food, and it was a Picasso painting,” recalls King. “Get rid of the monetary value. No monetary value, what do you like? What do you want to live with?”