-

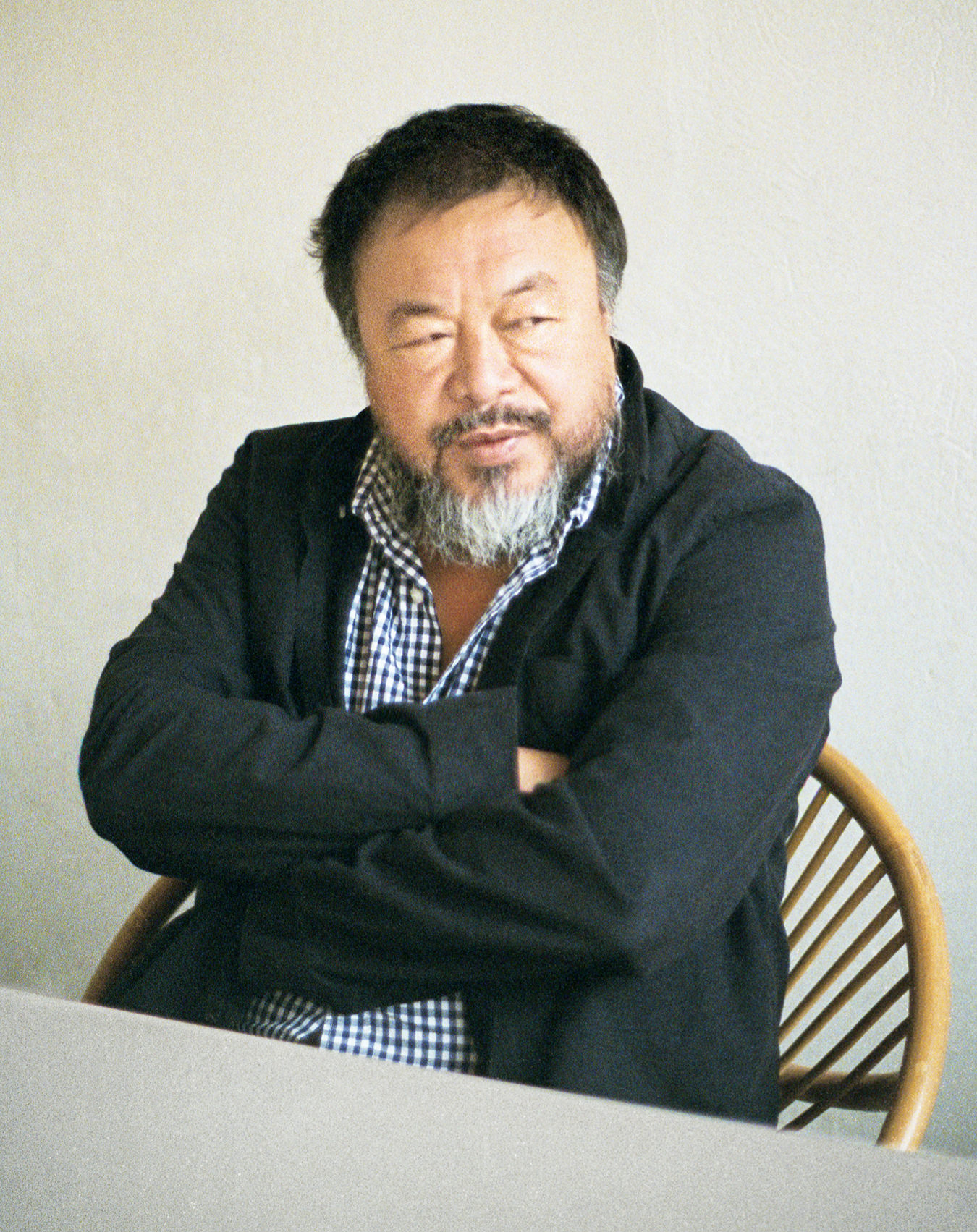

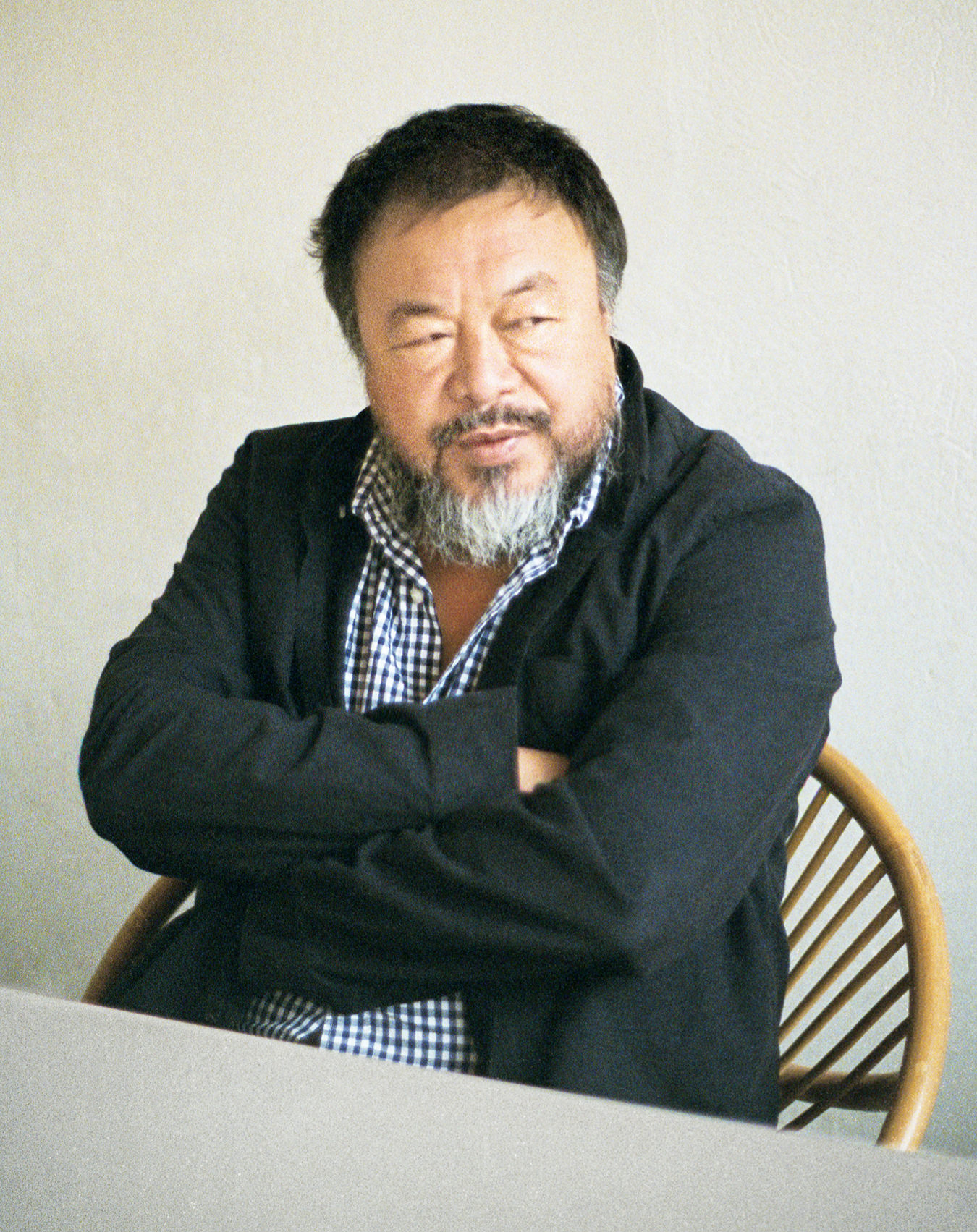

Ai Weiwei.

-

Ai Weiwei’s studio and home in Caochangdi, Beijing, where the artist is primarily confined to.

-

Bang, 2010–2013, 886 antique stools, shown at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

-

Every morning, Ai Weiwei’s studio hands place fresh flowers in the basket of the bicycle outside his studio. They will continue to do so until Ai’s passport is returned to him.

-

A delivery to Ai Weiwei’s studio and home in Caochangdi, Beijing.

-

Ai Weiwei.

-

Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, 1994, Urn, Western Han Dynasty (206 BC–24 AD), paint, 25 x 28 x 28 cm. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

-

Ai Weiwei’s studio.

-

Surveillance cameras outside Ai Weiwei’s studio.

-

Ai Weiwei’s studio.

-

S.A.C.R.E.D, 2011–2013, six dioramas in fiberglass and iron, shown at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

-

The garden at Ai Weiwei’s residencw.

-

Inside the grounds of Ai Weiwei’s home.

-

Straight (detail), 2008–2012, steel rebar. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei

Long-distance relationship.

Ai Weiwei.

Ai Weiwei is coming to Vancouver. But Ai Weiwei isn’t going anywhere.

The 57-year-old artist, architect, activist, father, and sometime political dissident is sitting at an ad hoc conference table in his studio in Beijing. He’s been dislodged from his preferred meeting place, the airy, high-ceilinged dining room in the apartment he keeps on the far end of this private compound in the northeast of the city. Fifteen years after he first moved in, a leaky roof has begun to warp the exposed wooden floors of his living quarters, and workmen are floating in and out, hauling up the boards and replacing them. The bang and bustle of the renovation brings an unwonted bit of commotion to the otherwise tranquil confines of the Ai encampment.

Centred on a modest courtyard planted with pine and fruit trees and spreading Chinese shrubs, the enclosure of grey brick buildings is very much Ai’s world, as indeed is the entire neighbourhood that surrounds it. Caochangdi was a remote farming village when the artist and a group of like-minded friends began migrating here. By the late nineties, Beijing’s creative types were looking for a new urban niche (the 798 Art District, a former industrial zone that went from no-man’s land to bohemian enclave to ritzy redoubt, had become increasingly commercialized), and Ai all but built it for them: through his design practice Fake Design (which no longer exists as an entity, having been shut down by the Chinese authorities), he designed a network of galleries and studio spaces in Caochangdi, much in the style of his own headquarters—all austere brick walls with interior piazzas of grass or concrete—while leaving intact the winding streets of the surrounding hutongs, redolent of frying jian bing crepes and chuan skewers from the local vendors.

The visitor is only certain of having arrived chez Ai by noticing the bicycle chained to a post just outside the heavy steel door of the studio, its basket always overflowing with fresh flowers put there by Ai’s team of young studio hands. The revolving crew of helpers take good care of their little corner of Beijing, and of their patron, hustling him from the front gate to the waiting car, from meeting to meeting, checked somewhat in their headlong progress by the artist’s natural garrulousness and his fondness for posting photos of himself to social media, a thing he does several times daily, to the delight of the total strangers who often pose with him.

And right now all of this—the Instagram shots, the watchful eyes of his assistants, the little world of Caochangdi and the drab ring of buildings with its immobile, bouquet-bearing sentinel out front—all of it is coloured with, and shadowed by, the knowledge that this is nearly all of the world that Ai has been able to see.

The garden at Ai Weiwei’s residencw.

“On April 3, 2011, on the way to the airport to see a site before an exhibition, I was arrested and secretly taken to an unknown location.” Ai’s voice is measured, contemplative. “Then, after 81 days of secret detention and interrogation, scaring me by telling me how I could be sentenced for 10 years, suddenly I was just released without any prewarning. The same way I was arrested.” Upon his release, and on the pretext of ongoing additional litigation that has included charges ranging from tax evasion to adultery, Ai has not been permitted to obtain a passport or to travel abroad, and indeed only in recent months was he granted the right to move around the country with relative freedom.

Working at a remove of thousands of kilometres has quickly become an intrinsic part of the artist’s practice. “I’m used to it,” says Ai Weiwei. “We have a brilliant team, all very young people, creative, educated, and they extend the studio.”

As a result, one of the most recognizable artists on the contemporary scene has not been able to install his own work, attend his own openings, see art fairs, or drop in on his assorted gallerists and collectors the world over. “The exhibitions that I can attend are much less than the exhibitions I am forbidden to attend,” notes Ai, a fact that, he jokes, deserves some recognition. “Nobody can break that record.”

Working at a remove of thousands and sometimes tens of thousands of kilometres has quickly become an intrinsic part of the artist’s practice. “I’m used to it,” he says. “We have a brilliant team, all very young people, creative, educated, and they extend the studio. You know they have the ability to make it happen.” Thanks to them, and to the outpouring of international support that’s come from every corner of the art world since Ai was first detained, the artist has managed to seem ubiquitous even in his confinement: At the 2013 Venice Biennale, he was represented by no less than three separate installations (specifically, the works Bang, Straight, and S.A.C.R.E.D.). And between now and the end of the year, he has a project that’s just debuted on San Francisco’s famed Alcatraz Island; a travelling show of sculptural masks that’s recently landed in Mexico City; and of course a major new outdoor public art work that is set to be unveiled in British Columbia as part of the Vancouver Biennale.

When reports of his arrest first hit the Internet, a popular meme sprang up on Twitter and elsewhere, even popping up on bus shelters in Berlin, demanding information about the artist’s whereabouts: “Where’s Weiwei?” The answer now is: Weiwei is everywhere.

And yet the man at the long table in the small room in Beijing, distractedly checking his phone at intervals and speaking in tentative but nuanced English, did not have the air of someone luxuriating in his success. “There’s only so much we can talk about,” says Ai.

Ai Weiwei.

His English, and perhaps some of his wizened reticence, comes from his having spent nearly 12 years as an American. From the early 1980s through the early ’90s, Ai lived primarily on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, acquainting himself with Western art, meeting prominent cultural figures like Allen Ginsberg, and acquiring at least a touch of Yankee insouciance and independent-mindedness.

He returned to China in 1993 to look after his ailing father. Ai Qing, who died in 1996, was one of the most prominent Chinese poets of the 20th century, and his story is both a prologue to and an augury of his son’s. Qing’s early Communist sympathies did not spare him the wrath of Mao’s regime, and he was eventually expelled from the party and sent into exile in a remote corner of the country. The hardships and privations that followed were the background of Ai’s childhood, and they informed his distinctly jaded view of the People’s Republic of China (PRC).

Ai the Elder’s reaction to the hardships visited upon him by the ruling order seemed to be a kind of resigned, melancholy fatalism; his son, on the other hand, appears determined to be neither bowed nor broken. On his return to China from the United States, Ai had already built up a catalogue of engagingly avant-garde work, including an exhaustive photographic record of his days wandering the streets of New York and still earlier projects from his student days at the Beijing Film Academy. But the direction his practice took after he returned home was still more daring: in 1995, the artist executed what almost certainly remains his best-known work, Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, three oversized photographs of a performance in which Ai first holds, then releases, then lets smash to bits on the ground a 2,000-year-old ceramic vase. This followed on his breakthrough Han Dynasty Urn with Coca-Cola Logo, another ancient vessel done up in the trademark colours of the world’s favourite syrupy soda.

These iconoclastic icons were an announcement of Ai’s intent, and of his whole attitude toward Chinese life in the late 20th century. Their aim would seem to be a triple-coded critique: On the one hand, defacing these priceless artifacts is a reminder of the violent historical uprooting in China experienced during the Cultural Revolution, the political upheaval of the 1960s and ’70s that contributed to his family’s misfortunes and that the present PRC government has been eager to sweep under the rug. On the other hand, it’s a stinging indictment of the ongoing destruction of Chinese national identity taking place as the country rushes headlong into commercial, capitalist culture, a result of the pro-market reforms that have taken effect here over the last few decades. And at the same time, it’s simply an acte gratuit—a wanton gesture, angry and self-assertive—that marks a break with the purported Chinese tendency toward meekness and submission, the kind of attitude that characterized Ai Qing’s generation. In 2000, Weiwei curated an exhibition in Shanghai during the city’s third biennale. Its two-word title became a major refrain for his entire practice: Fuck Off.

When you have to make yourself understood while communicating through a filter of distance, surveillance, and censorship, it’s important to speak succinctly.

That sentiment is key to much of what Ai has been up to recently in his semi-seclusion, and of the public work he’s bringing to Vancouver. The very name of the neighbourhood where he finds himself a partial captive, Caochangdi, bears its echo: “This village is called ‘Grass Field,’ ” explains the artist. “In China, the word cao, grass, is pronounced in many different ways. And this sound, cao, it also means fuck.” In a country where Google, Twitter, and Facebook have been either censored or blocked, “grass” has become a very freighted word. “On the Internet, because there’s so much censorship, they have to use other words to replace the words that can be picked up by the secret police,” says Ai. “They cannot say ‘fuck’, so they say ‘grass’.” One of the artist’s most provocative pieces (and one rumoured to have incited his trouble with the authorities) was a 2009 photograph of himself, naked, with what appeared to be a toy llama over his genitals. The title, roughly translated, was Grass Mud Horse Covering the Middle; given the slippages in Chinese speech, an alternate reading could be “Mother-Fucking Communist Central Committee.”

Ai Weiwei’s studio.

His piece for Vancouver, F Grass, continues the theme. “The installation looks like a field,” Ai says. “It’s a covering about 20 centimetres high, about 50 square metres in area, of metal-cast pieces of grass.” Each unit of the installation is composed of a hexagonal iron base that clips into its neighbour’s; protruding from the top of each are three slender vegetal forms, like thick blades of grass. “The iron, when it’s being shaped and settled, rusts into a reddish-brown colour,” he continues. “And those grass pieces together make the letter F—kind of like handwriting, or a piece of type.” The installation, scheduled to be unveiled in November, makes a bold public statement in giant, spiky metal form laid out on the lawn of Harbour Green Park, spelling out a familiar, and very suggestive, message. “Ai was given nine different sites to consider,” says Barrie Mowatt, founder and president of the Vancouver Biennale, “and he chose this one”—the city’s Coal Harbour high-traffic location.

Ai is charmingly coy about what precisely that message is meant to convey. “The letter F stands for letter F,” he says, in admirable deadpan. “It could be for words beginning with F, or that have F in the middle, or that finish with F.” In consideration of the double meaning of “grass”, however, there seems little doubt as to which vulgar expression Ai means to project back toward his own country from the distant shores of the Pacific Ocean.

But to focus too much on that particular four-letter word is to miss the deeper note of defiance sounded by the piece’s materials and process. As the artist explains, “It’s not a statement. It just has an associative quality, maybe.” Iron, for example, is “a very special material,” one whose extraordinary strength and durability ushered in a new, prosperous era when it arrived in China in the third century BC. Its application in this context gives it a special resonance. “You know, grass is this vulnerable, weak, seasonal plant,” continues the artist, “and normally I relate to a lot of fragile things, things with no way to resist any kind of force.” Through this unusual alchemy, in which tender blades of grass suddenly become so hardened and tough that “you can’t even drive a tank on [it] because it’s more like a blockade,” Ai is making a resounding declaration of protest, one especially poignant to those familiar with Chinese history. “In the Yuan dynasty”—during the 13th and 14th centuries—“people threw pointed pins, also casted, on the fields so it would hurt horses’ hoofs.” F Grass isn’t just a rude gesture. It’s an act of rebellion, an installation as much in the artistic as in the military sense of the word.

Bang, 2010–2013, 886 antique stools, shown at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

That it was created, as so many of Ai’s installations must be, in a small studio on the other side of the world only adds to its significance. “It’s always on my mind to make work smaller, make it shaped and assembled simply, by almost anybody,” says Ai of his creative-process-by-proxy. The result has been work that’s “more direct, that looks less complicated”: for his Alcatraz project, the artist created portraits of political prisoners around the world out of Lego blocks, a construction system so simple that it can be modelled in his studio and then executed on-site with relative ease. Not being able to travel has refined Ai’s practice, forcing him to be still more emphatic, more plainspoken. When you have to make yourself understood while communicating through a filter of distance, surveillance, and censorship, it’s important to speak succinctly. In this instance, one letter is better than four.

All of which is not to say that Ai has become so accustomed to his predicament as to make it a natural part of his art and outlook. “People celebrate this kind of language,” he says, speaking of the “online grass-o-phone” culture that has residents using the code word in their swear-laden critiques. “But that’s sad, because there’s no way you can smoothly let your thinking or intellectual state of mind be discussed. Everything has to be symbolic.” If he didn’t have to produce art this way, it’s obvious that he wouldn’t. “A nation or a party should not do this kind of thing to people,” he says.

“I want to let my voice be heard,” says Ai Weiwei. And so it has been, to a degree that practically no other Chinese artist of his generation has ever been before.

It’s somewhat surprising to hear such an earnest social and political aspiration from someone whose public persona has long been that of the irreverent, vase-dropping punk. But at the heart of Ai’s cultural project has always been a sincere humanism. In addition to F Grass, his Vancouver Biennale participation will include a screening of Stay Home!, a documentary film created by Ai’s studio that chronicles the travails of a young HIV-positive woman as she tries to navigate the cruel and indifferent Chinese medical establishment. The problems she faces are symptomatic of the contemporary political order, says Ai (“The government keeps them a secret, because here anything can be a secret”), but the film seeks to make its case less through polemic than through an appeal to the humanity of the viewer. “The whole story is about her struggle. It’s a very ordinary story, with a very kind of extraordinary lady,” says the artist.

“I just want to make sure they don’t do the same thing to others,” says Ai. His empathy for his countrymen is authentic—but he is still himself dealing with how to navigate the practical conditions of China today. Another film that will appear in Vancouver is The Fake Case, an account of the artist’s ongoing dispute with the Chinese legal system following his arrest. His earlier run-ins with the authorities left him with a demolished studio space in Shanghai and a serious head injury that required emergency brain surgery; it’s a level of violence that has been directed at few other artists in China, and sometimes it seems that Ai is going out of his way to make a martyr of himself, with social media spreading his particular political gospel. “I want to let my voice be heard,” he says. And so it has been, to a degree that practically no other Chinese artists of his generation, or of any generation, have ever been before.

S.A.C.R.E.D, 2011–2013, six dioramas in fiberglass and iron, shown at the Venice Biennale. Photo: Ai Weiwei.

Around Beijing, that stature has elicited some debate. Just walking around the galleries of Caochangdi one confronts the thriving contemporary art scene in China today. At parties during the city’s Design Week, figures from across the creative spectrum expressed mingled feelings about the artist’s seeming cultural hegemony; stories even circulated of Ai having confronted, at least once physically, a fellow artist whom he deemed insufficiently opposed to the Communist Party. Similar criticisms could be heard at the last Venice Biennale: despite Venice being the setting for China’s first-ever permanent pavilion, which opened during the 2005 event, the focus of almost all media attention was on the installations scattered around the city by the famous Ai Weiwei.

For his part, the artist seems unpreoccupied with his art-world standing, inside or outside his home country. His concerns, as he sits with his hands tented over his cell phone, appear to centre on the quotidian problems of running a studio, dealing with his legal case, and raising his now five-year-old son, Ai Lao, who is the product of an extramarital affair. (Lu Qing, Weiwei’s wife, is also an artist.) His assistants say the boss is amazingly, almost hyperactively keen to take on new projects, and with each one—in addition to all the complex logistical issues that have to be resolved just to get the work to Vancouver, or to San Francisco, or to wherever it might be—the questions Ai must have to ask himself are: what will they think of this one? And when will they let me see it? And how will all this end?

They aren’t always questions that he can speak about candidly. There is only so much in “only so much we can talk about,” a point that seems especially salient today: as soon as he leaves the conference room, Ai has to rush off for a lunch he can’t afford to be late for. It is with the chief of police, with whom he evidently maintains a prudent cordiality and who plainly likes to keep tabs on the wayward artist-architect-filmmaker.

For now, Ai Weiwei isn’t going anywhere. But Ai Weiwei is coming to Vancouver.