The Work of Italian Designer Andrea Mancuso Goes Beyond the Boundaries of Design

Poetic objects.

Custom states that for a 10th anniversary, the gift you present to your partner should be made of tin. A somewhat banal material, it represents strength and resilience—qualities undoubtedly required to nurture such a long-lasting relationship. But what material do you use if you are a designer and the 10-year anniversary is with your gallerist? For the founder of design studio Analogia Project, Andrea Mancuso, who at 2024’s Milan Design Week celebrated a decade working with Milan’s Nilufar Gallery, run by the superstar gallerist Nina Yashar, that material was stone. More specifically, his latest exhibition, Pentimenti, encompassed three new collections of stone tables as well as blown-glass lighting.

I meet Mancuso on a blustery day in late March at Nilufar Depot, the second location of Yashar’s gallery in the peripheral Lancetti District of Milan. The original gallery, designed by Milanese architect Massimiliano Locatelli in 2015, was configured to echo the proportions of the city’s revered opera house, La Scala. A sunlit central atrium is ringed by two storeys constructed from steel girders meant to look like the theatre’s red-velvet-clad boxes. With Salone del Mobile just a few weeks away, when I enter the cavernous former industrial space occupied by Nilafur Depot, the gallery staff is in the midst of a multipronged install. Each of the Depot’s three floors will soon be animated by carefully arranged mises en scène composed of avant-garde furniture from the industry’s most sought-after contemporary designers and rare artefacts from midcentury masters. But now, teams of worried-looking art handlers wearing work gloves are carefully unpacking wildly creative sofas, armchairs, and lighting.

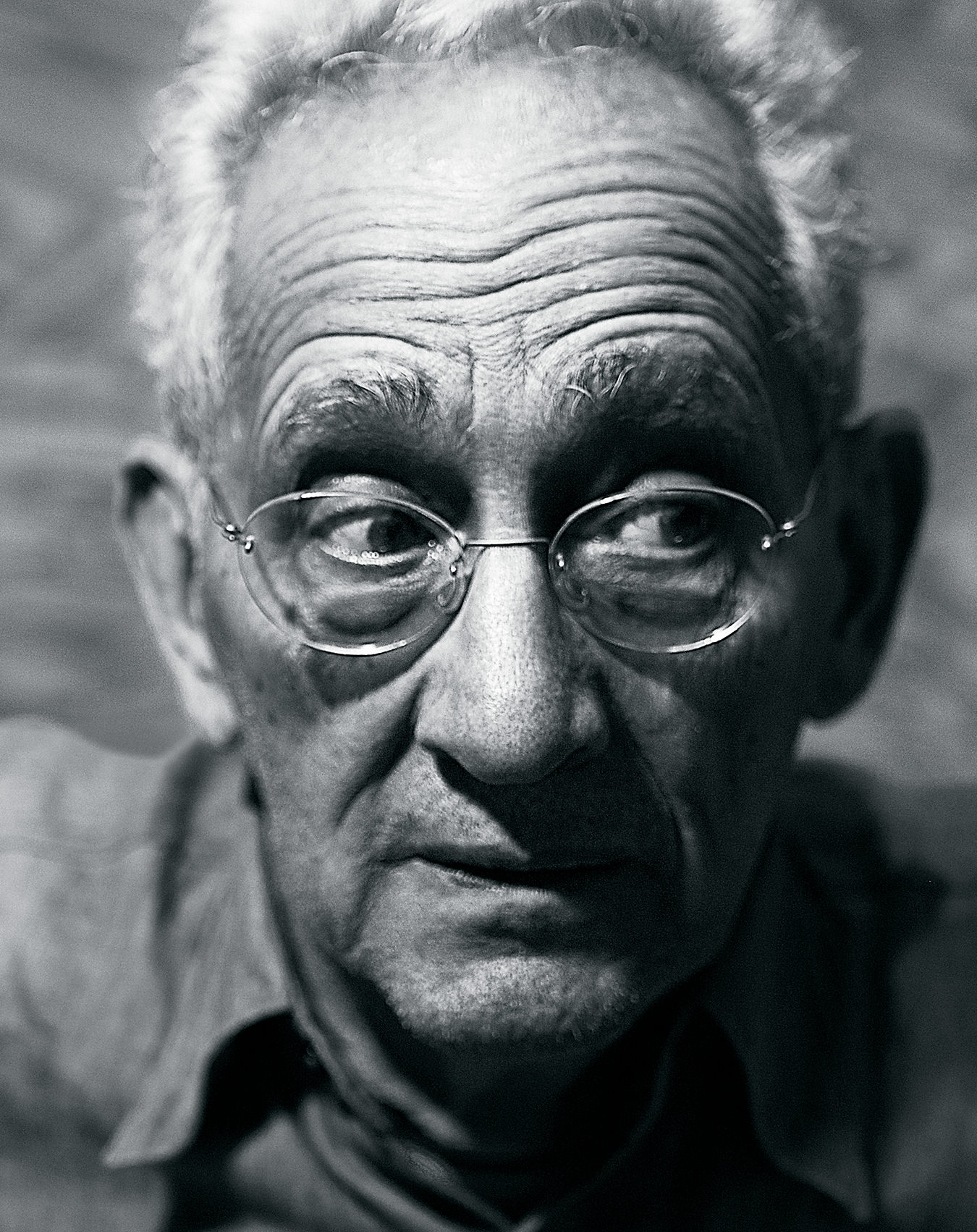

Andrea Mancuso at the Ferragamo flagship on Via Montenapoleone in Milan, where Aquario, a feature wall of mounted discs, resides.

Since Yashar founded the gallery in 1979—initially to sell rare Persian rugs—she has grown it into one of the most respected destinations for contemporary and vintage design globally. The first location is on the tony thoroughfare Via della Spiga in the Quadrilatero della Moda shopping district. But when the Depot opened, it heralded a shift in Yashar’s approach as a curator. It became the more exploratory arm of the gallery, where young and emerging designers have more freedom to experiment.

When Mancuso began working with Yashar in 2013, he had recently returned to Italy after spending five years in London. Following his graduation from Rome’s Sapienza University in 2006, he had moved to the United Kingdom, where he landed a job with the eccentric British architect Nigel Coates. “I worked with Nigel Coates for five years,” Mancuso recounts. “At the time, he was head director of the architectural department of the Royal College of Art and had his own studio inside the college.” Mancuso describes those formative years in London as eye-opening for him as a designer. “With Nigel, I discovered the kind of storytelling an object can have,” he says.

Analogia Project’s first major exhibition came in 2011. Mancuso and former studio-mate Emilia Serra were invited to present an exhibition, Analogia #0001, at the London Design Festival. The perception-bending installation took the form of a two-dimensional sketch of a full-scale living room rendered in 3D. What seemed from afar like a hastily drawn table, chairs, and vase with flowers were in fact thick black wool suspended by nearly invisible fishing wire. The project sparked the attention of the press and international curators alike and led to Mancuso and Serra being invited to recreate the concept in the windows of Hermès boutiques in Tokyo and Dubai and during Milan Design Week in 2012. A wave of commercial and creative collaborations with brands like Fratelli Boffi, Poltranova, and Frag followed. After spending several years commuting between London and Milan, Mancuso settled in Italy full-time in 2013. The return to Italy also led to a growing number of commissions from coveted Italian brands. They began collaborating with fashion houses like Fendi, Bulgari, and Etro on store and window displays.

Sgraffito Table is made by engraving on marble, echoing an ancient technique used for the inscriptions on monuments and tables in the past. The engraving on the marble is then completely covered with ink and once deposited in the cracks of the excavated part it is absorbed.

Andrea Mancuso engraving the marble of his Sgraffito Table.

Serra left the studio shortly after to pursue her own projects. But over the past decade, it has been Mancuso’s collaboration with Nilufar that has largely defined his trajectory as a designer. “At the beginning, Andrea proposed to me an amazing light fixture that I still really love,” Yashar says. “And that started our journey together.” Among those early lighting projects was the Blossom series composed of thin brass profiles shaped to almost resemble paper lanterns. “But over the years, he has really evolved to create some incredible projects,” she adds. According to Mancuso, however, the relationship was a slow burn. “I’m not a person that wants your confidence immediately,” he reveals. “A good relationship takes time, and over the years and over many collections, we have built up a strong one.”

The relationship between a designer and their gallerist is often defined by push and pull. The creative’s ideas are often larger and more elaborate than the commercial concerns of the gallery allow. But Mancuso insists they are on the same page. “It’s always a dialogue with Nina,” he says. “We both often have crazy ideas, but mine are about creating objects, while she has the knowledge about how to make those ideas real. She can immediately see how an object will live within a space—and how the public will react to it. In collectible design, you always imagine your work to live in a gallery environment. You want your piece to stand alone rather than communicate with other objects in an interior. So what has been important about working with Nina is understanding how she sees your work in a different context. The piece can be very sculptural, you can put a lot of research into experimenting with materials, and ultimately it can be very close to a piece of art. But in the end, it has to be functional. And it takes a good curator to understand how to work with that.”

Indeed, Mancuso’s collaboration with Nilufar has seen his work evolve from pared-back material-focused objects to wide-ranging collections with sweeping narratives that play with more abstract concepts, often stemming from inspiration found in the natural world. For instance, his 2018 collection of tables, Goldfish. Each piece is composed of a plane of greenish-blue marble set atop a curved brass base. Inlaid with red stone in the shape of swimming fish, the table top mimics the surface of a koi pond. “It was one of those simple gestures that creates a smile and pleasant reaction,” Mancuso says of the design.

Stria Bench in Guatemala green marble, Antigua green marble, cement, and steel.

In 2022, he returned to the water theme with the Acquario series, a collection of softly curving tables, a console, a pendant light, and a mirror seemingly encrusted with concave ceramic discs that resemble rock pools and frothy waves. Each hand-formed disc has different dimensions and glazing; some are finished in deep indigo, others a pale but mottled turquoise, with a range of shades in between. “With Acquario, I wanted to explore the idea of bringing the natural world into the domestic landscape,” Mancuso said at the time. “In the same way that one introduces an object like an aquarium or terrarium into the home, I played with the idea of extracting nature from its original context. The shapes of the objects are not literal recreations of living organisms but rather are meant to evoke the artificial nature of these confined habitats.” Recently, Mancuso has expanded Acquario in collaboration with the Italian fashion house Ferragamo, which commissioned him to furnish its Milan flagship with the collection earlier this year. And in early 2025, the Waldorf Astoria in New York will unveil a site-specific fountain made for the hotel’s wellness area.

Analogia Project’s work, however, does not simply rely on storytelling to make an impact. What sets it apart is a focus on craftsmanship. Mancuso often works closely with artisans to realize his ideas. When developing a project in marble, for instance, he seeks out stone workers in Veneto or Tuscany and works with them directly every step of the way instead of simply sending a sketch or a rendering. For glass, he will travel to the master glassblowers in Murano, near Venice. According to him, his most recent collection proved a particular challenge for the Muranese artisans. To make his Sgraffito lamp—which resembles a balloon trapped in a spiky cage of bronze rods—the glassblower was tasked with figuring out how to inflate the molten glass within the metal structure. The result is meant to communicate a sense of tension, as if the glass vessel is bursting from the frame. “They’re quite big pieces,” Mancuso says. “So they have to heat up the bronze, then quickly blow the glass inside. The blower has to understand how the glass moves inside the structure, because otherwise, it becomes too fragile. Then, once they’ve made the shape, they have to run it to the kiln to cool down for two days. The process is so quick you only have about three seconds to see the shape, and there is no way to intervene once it’s finished.”

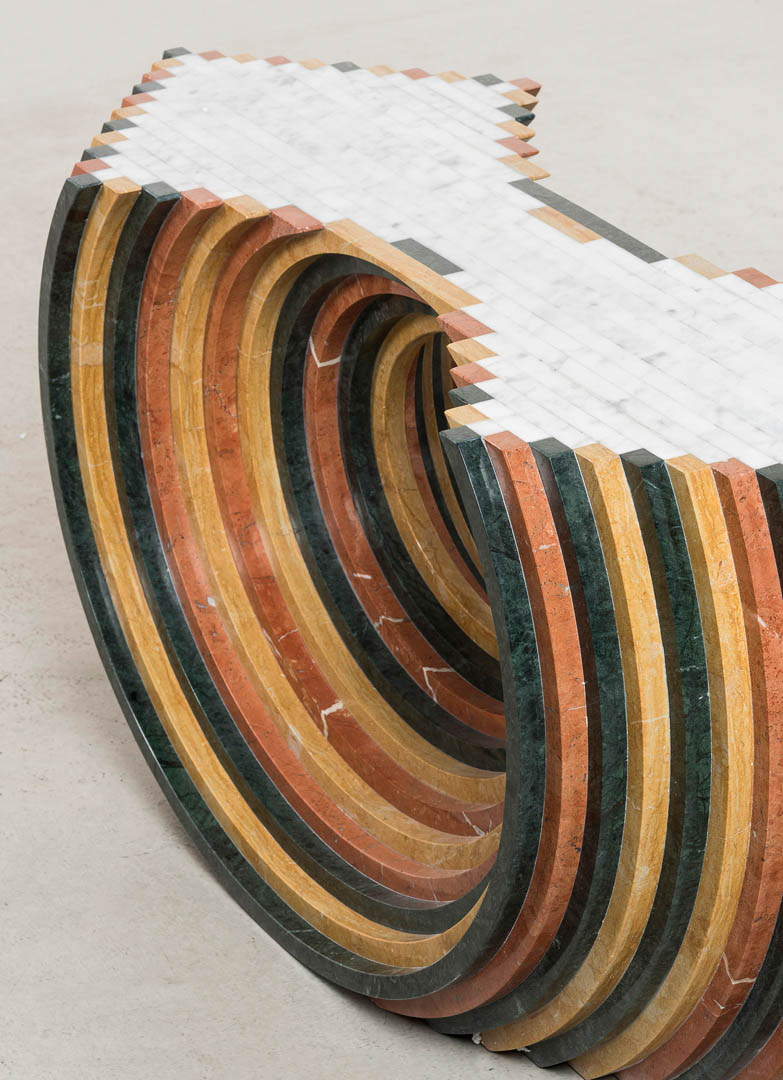

Strata Low Table with insets of Carrara marble, Guatemala green marble, Antigua green marble, Marquina black marble, and steel.

Mancuso is explaining this nail-biting process as we wander through his dedicated exhibition space on the Depot’s second storey. Around us, the gallery staff are testing the lighting for the exhibition that’s opening in a few weeks. Some of the pieces are already on display, while others are still packed in boxes like pharaohs bundled in their sarcophagi under stark white spotlights. It’s not the only item that recalls ancient practices. Among the new pieces Mancuso produced for the Milan Design Week presentation is the Sgraffito table—the companion to the Sgraffito lamp—a monolithic stone plinth that looks as if it has been engraved with a primitive form of hieroglyphs. “I experimented in the studio using different tools to draw on marble,” Mancuso explains of the development of the pieces. “It’s the same technique used since the Stone Age to transmit knowledge and history. Writing on stone is where it all began.”

The various ways one can slice and arrange stone is a significant undercurrent of the exhibition. Another series of tables, Strata, resembles a Venn diagram. What look like thin, overlapping layers of semi-transparent materials are in fact a jigsaw of different coloured stones. The Stria collection, meanwhile, looks like a brush stroke exploded to full scale: a round, three-legged table is made of meticulously cut strips of different colour stones cut on an angle. Each piece is arranged side by side, and a complementary-toned concrete connects the disparate pieces, resulting in a composition whose seemingly spontaneous origins belie the artistry that went into its creation. A similar bowl is made with strips of coloured glass melted into one another to create a single concave shape.

The Pentimenti exhibition represents research Mancuso has been conducting for nearly four years. So when asked what he has planned for the future, his response is surprisingly zen. “I like to see things grow slowly,” he says. “I opened the studio 13 years ago, and now I’m getting older. I’m not rushing to have everything at once—I just want to enjoy it while it’s here.”

Arcoiris Collection Coffee Table in Carrara marble, Guatemala green marble, Giallo Reale marble, Alicante red marble.