-

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems, 1987–2011 by Peter Gizzi.

-

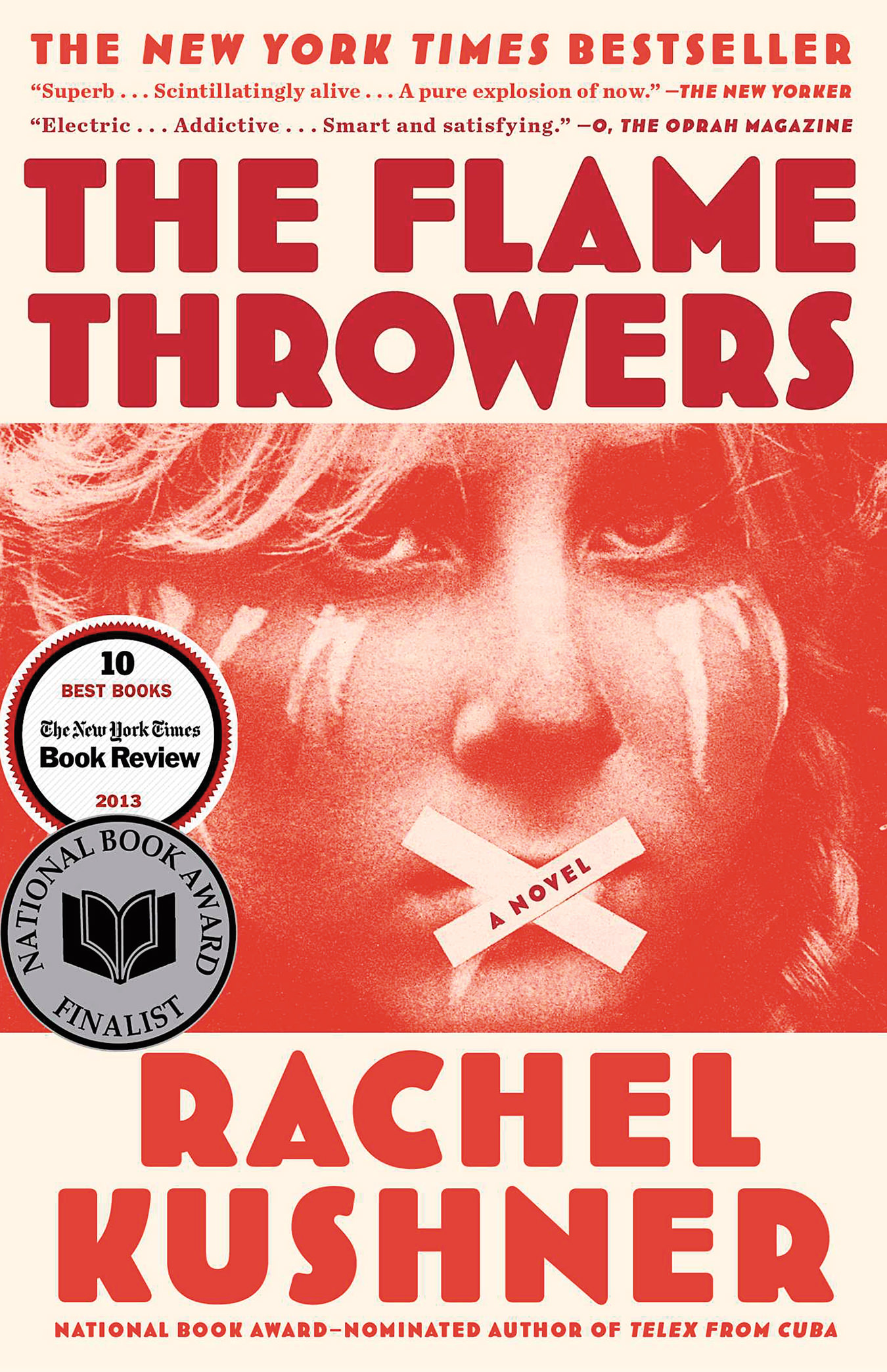

The Flamethrowers by Rachel Kushner.

-

Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room by Geoff Dyer.

Off the Shelf: Echoes of Empire

Books by Rachel Kushner, Geoff Dyer, and Peter Gizzi.

Many contemporary novels, however enjoyable, seem content tracing the doings and events and psychologies corralled inside their clearly delineated piece of fictional terrain. They seem never to be about more than their characters’ stories. These books have a long tradition, of course, to honour, but when they fall short of their potential, an air of the inconsequential can drift through. Other novels, however, throw open the windows and let the world’s chaos blow throw a narrative.

The Flamethrowers

Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers earns every sizzling descriptive for boldness, scope, expansiveness, and virtuosity—and perhaps even the old-school badge of engagement. Her plotting may not be entirely seamless, but what The Flamethrowers gives up in story it more than makes up for in high-octane prose, a cool worldliness, and riveting cultural tableaux. The novel’s bones constitute a solid Bildungsroman. A young artist from a working-class background moves to New York from Reno, Nevada (throughout the novel she’s known only as Reno), but instead of chasing hard-headed, blinkered ambition, she finds herself buffeted, drawn in, sandbagged, and consumed by the Lower East Side art scene of the 1970s. Adjacent to the centre of the story is Reno’s romance with Sandro Valera, a revered minimalist who sits in the quiet eye of a gathering storm: the now-familiar madness of the eighties art bubble. It is a Manhattan of radical politics, rivers of heroin, all manner of post-art theorizing and windbagging, and the decline of New York’s unchallenged cultural centrality. The place is peopled with wing nuts and geniuses in equal measure—and at times it’s impossible to tell one from the other. Kushner’s characters know how to talk. We’re as convinced by the bullshitting as we are by the glimpses inside the psychologically aberrant.

Valera keeps his family history quiet. The Old World Valeras in Italy are a massively wealthy industrialist concern with interests in rubber tires, motorcycles, and auto parts. This wealth was built on the deeply exploitative labour practices, verging on slavery, that the rubber extraction company pioneered by Sandro’s grandfather, then taken over by his father, prefers not to see. Mirroring parts of Reno’s own psyche, Valera Sr. was a speed-loving proto-Fascist who rushed to the front during the First World War, more in love with the features of warfare than any particular cause. The Valera factories now face not just labour unrest but the intense structural turmoil of Italy’s fractious and extreme politics that strangled the country during the seventies. History is up on its horse in this book.

But when Reno accompanies Valera to his family villa, her lover’s immediate family proves a personal nightmare. She is shot through with a sharpening awareness of class and the unshakable world view of the ultrarich. It’s here, in Italy, that world events encroach on Reno’s private, emotionalized notions of love and loyalty. Her centre does not hold. And without warning, she’s in Rome, via the surly groundskeeper (with a double identity) from the Valera estate, crashing among bodies of strangers, drifting toward street clashes with riot police, running with Red Brigade militias, an accomplice to acts she’s not fully cognizant of. And how could she be? The intersection of our private, desirous self with the trade winds of history is not a crossroad we can have any perspective on. Our choice to act, or not, with what information we have, is a kind of loser’s gambit. We may never even be privy to ultimate consequences. Kushner’s novel is a dynamic, astute, outrageous, and lonely reminder that to not make the effort is to sink into the shadows of the barely human.

Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

If The Flamethrowers takes place in the vacuum that’s appearing in the United States’ tottering, fissured centre, the United Kingdom’s Geoff Dyer has trained his laser-eyed weirdness on his own empire’s most beloved arch-enemy, Russia—or, at least, a darkened, swirling corner of it—in his unnerving book Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room. The book, though ostensibly fiction, drags the long tail of its subtitle for good reason. The film in question is Andrei Tarkovsky’s Stalker, a 1979 art film running 163 minutes. The room, the stalker, and his clients, a writer and a professor, travel to at the centre of the zone is a derelict, postindustrial shell lying wasted in the drizzling forest, only arrived at after evading military checkpoints, interminable ennui (character and viewer both), flooded tunnels, and the depopulated, mysteriously verdant zone. Said to magically manifest any visitor’s deepest desires, the Room of the Film in the Book serves as Orphic symbol, or void, or negative projection. It’s unclear if Tarkovsky himself knew what it was meant to represent. In any case, Dyer won’t let ambiguity and punishingly long, moody single takes deter him from his own contemplative, hallucinatory, and wickedly funny journey into obsession, pleasure, art, and time—a particular take, specifically, on the abstraction Dyer calls “Tarkovsky-time.”

Believe it or not, the book tracks the film scene for scene (at times the illusion of following frame by frame is fully in play), wandering off at the whim of the author to reflect on cinema-going, poetry, existence, ménages à trois, obsession, contingency, drugs, and our current version of the culture of the spectacle. It’s perhaps these very digressions—barbed with wit and wildly entertaining, confounding, and unpredictable—that contribute most to the sensation we’ve entered a zone ourselves, where time’s elasticity and circularity alters mental activity and can veer ferociously between levity and a dank, shadowy dread.

In the same way, and possibly for the same reasons, that Tarkovsky allowed no analogies to be read into his brutally action-less film, Dyer does an amazing trick of evasion and delay with regard to his own motives for writing such a genre-twisting beast. We learn often and early of his lifelong love of film, but why this particular choice of film is information saved for the essay-cum-memoir-cum-novel’s end—and it is not so much revealed as rolled out gradually in a powerful heating up of tone and focus, the dexterity of feigned intimacy quietly charging the prose. The Room at the Centre of the Zone breeds a palpable metaphysical fear in Dyer, and we’re in for a contact high.

In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems, 1987–2011

If there’s one true thing to be said about contemporary poetry in the United States, it’s that there’s presently a superabundance of it. I’ll go so far as to claim a large portion of contemporary American poetry is of a very high quality. From the older, established generation still writing at an intense pitch, right down to the younger poets publishing debut collections, the U.S. offers a continuing wealth of verse. Born in Pittsville, Massachusetts, in 1956, Peter Gizzi occupies—in terms of age—a position in the middle of the swarm, but his work is anything but lost in the muddle. Rare among poets, after five full collections, academic work, and many small indie-lit productions in the form of broadsides, chapbooks, and limited-edition prints, he seems never once to have suffered a dip in his powers. Gizzi has gone from strength to strength, plotting out—by intuition, sonic investigation, immersion in the tradition, and brute heart-song—a lyric course all his own.

The grandson of Roman immigrants, and the son of an important General Electric scientist, and for stretches a strung-out denizen of the seventies and eighties Lower East Side, Gizzi moved through drugs, punk, DIY, and on toward Ezra Pound, the tradition, the avant-garde, and independence—never damping his own white-heat hunger and vision. In Defense of Nothing: Selected Poems, 1987–2011 pulls work from across five collections and verifies his place as one of the most technically gifted, intellectually invested, and emotionally reverberant poets now working. A master at the longer lyric meditation, at extending song structure, he can as easily scorch a reader with briefer, fragmented, and unmoored visions.

“And why Gizzi? Why this poet of all the poets working?” This very question—posed by some understandably guarded, yet-to-be convinced, but willing reader—is itself an argument for reading him. Go into the gorgeously produced Selected Poems and you’ll hear the singular balance and assortment of qualities that give form to a believably sentient presence—a real absence:

Into luminous dusk into dust then scattered now gone

green then mint, blue then shale, gray and gray into violet

that nothing at the center of something alive and burning

though nothing might be the final and actual expression of it.

If the story of Europe’s colonization of the New World plays itself out in our minds, in our very habits of perception, then history, in a real way, resides in our heads. Can we resolve the grinding disagreement between matter and idealism that shapes us as a culture?

Music and the head’s harvest sound

and this blend of dissonance this

love of silence and aught

watches you, sees you (…)

These poems sing upward into our often-empty yearnings, yet never renounce the hard real of the world that houses us:

Cars in the yards

make ugly sounds

and the animals

touching them smell bad.

At times this disastrous binary plays out in unforgettable images. At others, it’s Gizzi’s exquisite ear combining lush, open-vowelled lyric nestled against a bitten and easy vernacular. This is American music in that the past lives within as an orphan, while the future is invited in as an intimate. Anyone can read Gizzi; anyone could read Gizzi for a lifetime.