Ken Babstock reviews Sontag: Her Life and Work by Benjamin Moser and Testosterone Rex by Cordelia Fine.

Ken Babstock

2 Must Read Books to Pass Late Summer Days

This fall we are reading two Guggenheim recipients’ collections of short stories that cut to the heart of the world we’re living in.

Two Books You Should be Reading this Summer

Our favourite reads this summer include a tale of Soviet espionage by Ben Macintyre and a posthumous collection of short stories by Lucia Berlin.

Just Our Type: Spring Reads

Books by Kassia St. Clair and Joshua Rivkin.

Just Our Type: Winter Reads

Books by Laura van den Berg and Miriam Toews.

Just Our Type: Fall Reads

Books by Rachel Cusk and Richard Sennett.

Just Our Type: Summer Reads

Books by Brian Dillon and Christopher de Hamel.

Just Our Type: Spring Reads

A woman’s life is upended after two strange sources report seeing her doppelgänger; a magisterial mélange of hard-core biology, philosophy, and octopuses around the world.

Just Our Type: Winter Reads

Books by Maggie Nelson and Jonathan B. Losos.

Just Our Type: Autumn Reads

A collection of short stories and the portrait of a young university student.

FYI Books: Something Old, Something New

A survey of humanity and a stunning collection of personal essays.

FYI Books: Timely Reads

Essential reading for spring.

Off The Shelf: Idle Hands, Loneliness, and Culture

Explorations of whether loneliness is a social malice, or something prehistorically determined, even necessary.

Off the Shelf: Playing with Platonisms

It’s a good time for scouring any vestiges of Platonism from one’s head.

Off the Shelf: Antibodies, Thinking Bodies, Nobodies

Vulnerability, confusion, and irrational fears.

Off the Shelf: Puzzles, Polemics, and Patterns

From games and gaming to puzzles and crafting, our preferences and tastes during leisure time can prove indicators of other aspects of ourselves, individually and as a social body.

Off the Shelf: Lost and Found

Forget everything you know about novels of the immigrant experience.

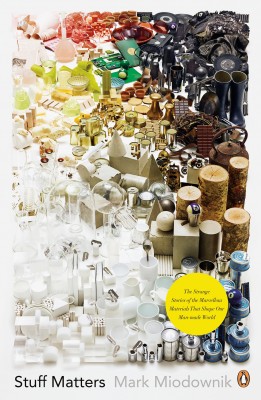

Off the Shelf: Material Worth

I do love it when a book with the word “enthralling” on its back cover actually turns out to be enthralling.

Off the Shelf: The Real Lives of Imagined Others

There’s no end to the catalogue of ways humans suffer, and manage to inflict suffering: illness and injury, psychic suffering, material deprivation, heartache, loneliness, catastrophe, separation, history, bad luck.

Off the Shelf: Mind Field

Consider for a moment the possibility that our very selves—our centred, internal, ever-present cluster of backstories we identify with the letter I—comprise as much everything we haven’t done as everything we’ve done. Everyone we haven’t become as much as who it is we find we have. Can anything useful be gleaned from the premise?

Off the Shelf: Echoes of Empire

Many contemporary novels, however enjoyable, seem content tracing the doings and events and psychologies corralled inside their clearly delineated piece of fictional terrain. Other novels, however, throw open the windows and let the world’s chaos blow throw a narrative.