-

The grounds of Tanque Verde Ranch in Tucson, Arizona.

-

Tanque Verde Ranch is the nation’s largest dude ranch, with around 170 geldings.

-

Tanque Verde Ranch houses the state’s largest stable of riding horses. Photo by Kimberly Budziak.

-

The wranglers are sharp, keeping each horse and rider’s safety top of mind.

-

There are many event spaces on the ranch with views of the Rincon Mountains. Photo by Kimberly Budziak.

-

At the Doghouse Saloon, Prickly Pear margaritas are the specialty.

-

The guest houses of Tanque Verde Ranch are southwestern in style.

-

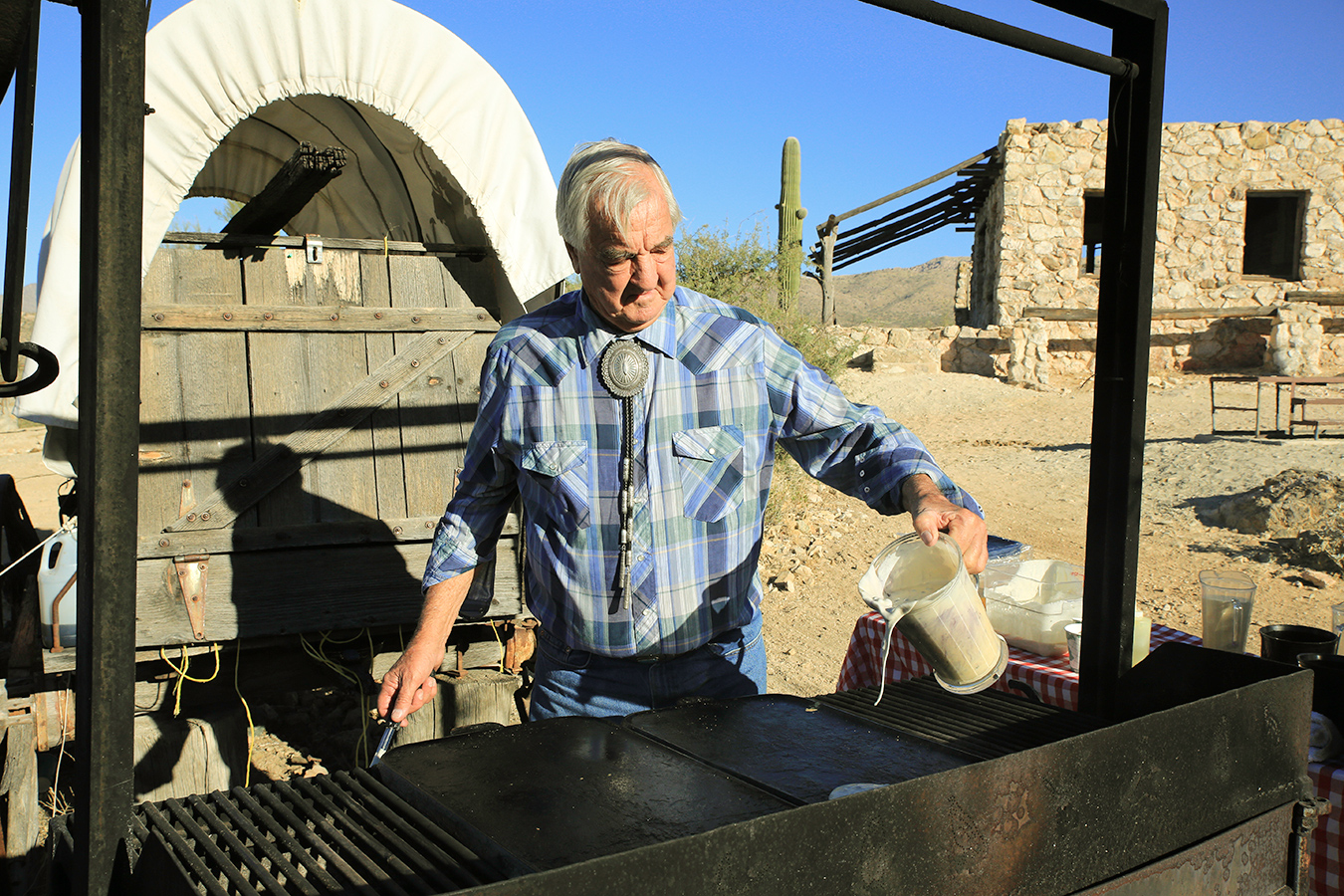

Ascend through the dry hills to one of the original homestead buildings on a breakfast ride. Photo by Kimberly Budziak.

-

Thursday and Sunday mornings ranch owner Bob Cote dons one of his signature bolero ties and flips pancakes (classic or blueberry).

-

Enjoy sunset rides any night of the week at Tanque Verde Ranch.

Tanque Verde Ranch

Ride on.

There is a moment when you first learn to ride horseback that suddenly everything clicks. You learn to let go and trust your partner—your shoulders drop from your ears, your breath calms, the energy around you shifts from focused apprehension to sheer delight—and the trot you’ve spent hours mastering graduates to a rhythmic lope. Given my country-city roots, I should practice more composure as I slow Sedona back down to a walk, but my enthusiasm cannot be contained. This is my moment.

The feeling is palpable at Tanque Verde Ranch in Tucson, Arizona, the nation’s largest dude ranch, nestled among the Rincon Mountains. The energy of the property radiates as far away as Speedway Street, the paved road that leads from Tucson proper into the desert where the 60,000-acre ranch resides. “People used to race hot rods here,” the driver informs me. This is in no way a foreshadowing of my upcoming riding experience—Tanque Verde is first and foremost a teaching ranch, where riders learn slow and steady.

The sprawling property is outfitted with multiple corrals and arenas to house and exercise the state’s largest stable of riding horses, which currently hovers around 170 geldings. The sound of the surrounding desert is punctuated with their whinnies and sighs. Some friendlier steeds hang their heads over the fence, waiting for a nuzzle.

At the Doghouse Saloon, Prickly Pear margaritas are the specialty, a cooling antidote to the dry heat. It is nearly empty in the evening—a regularity, the bartender admits. Over the course of my stay I learn why. Tanque Verde Ranch is brimming with daytime activities: tennis, biking, hiking, fishing, and of course, riding. By twilight, the property becomes something of a ghost town, the common areas are all but abandoned, save for the nights when “dive-in” movies are offered poolside.

Turning in early certainly has its perks. It seems nearly every guest is waiting at the stables to saddle up for a morning breakfast ride—a follow-up to the previous night’s sunset mosey. We ascend through the dry hills to one of the original homestead buildings where ranch owner Bob Cote dons one of his signature bolero ties and flips pancakes (classic or blueberry). It’s a relaxed walking pace that allows us to observe the local foliage, which includes fragrant sage and the jutting spires of the tall saguaro cactus (the state flower).

In a small arena, resident horse interpreter Lisa Bedient leads the Harmony with Horses program (usually held prior to rides, except on Thursday and Sunday mornings when breakfast takes precedence). “The harmony program is starting the horse’s day over,” says Bedient who moves without hesitation, looping each stallion’s reins securely through the pen’s fence. “Regardless of whether this is someone’s first experience with a horse, or if they have horses at home, we always start on the ground. We go over the way the horse sees, thinks, feels, looks at the world, and we really start building that relationship. Everything I do carries over to the saddle.”

After a thorough grooming during which I pick the dirt from Sedona’s hooves, massage his shoulders and haunch with curry combs, and brush the tangles out of his mane, we mount our horses and continue over to a larger arena where we practice our walks and trots.

The wranglers are sharp, making quick corrections and offering detailed feedback, keeping each horse and rider’s safety top of mind. Within just 24 hours, everyone’s progress is evident. In between lessons I participate in barrel racing, keyhole, and pole bending events and take home a second place ribbon in the team penning exercise.

I decide on a whim to try the Lope Check—the gateway to advanced rides. Riders cannot choose their horses for the Check, so I leave my chestnut Sedona behind and saddle up on Winston, a grey-white charger with a calm disposition. A barrel marks the starting point of our test, where wranglers scrutinize our rein position, seating position, and most importantly, ability to safely control the horse. I have two-thirds of the arena to demonstrate a controlled trot, lope, rein-directed turn, and full stop. I don’t pass, although I’m told I came very close, which pleases me, since most riders take five or six tries to graduate.

After a day on the range, a barbecue dinner of burgers, sides, and salads is served casually at Cottonwood Grove (Wednesday and Saturday evenings). The outdoor dining space is teeming with lush cottonwood trees and outfitted with gingham tablecloth–covered picnic tables. Pieces of soft fluff dance in the dry air. It is a real oasis, and one of the areas that lends the ranch its name.

“Tanque Verde means ‘green tank’. The ranch was originally built here because there was water,” informs general manager Jim Bankson. Nearby Lake Corchran, for example, is the reason the cottonwood trees exist. The ability to grow was a sign of prosperity in early days, and for the former owners of Tanque Verde, the success of the land was often mistaken for personal wealth. The original owner survived three separate hangings on the property when bandits demanded gold he didn’t have. The famous Chiricahua Apache leader Geronimo also had ties to the land, and another owner was likely a Freemason. The tall tales are reminders that this was ground zero for the Old West, and today, we relive it as we ride off into the sunset.