Vancouver Artist Adad Hannah Breathes Life Into Historical Masterpieces

Living pictures.

In his tableaux vivants, Vancouver artist Adad Hannah breathes life into historical masterpieces.

That’s me as a grasshopper,” artist Adad Hannah says as he points out individuals in a black-and-white photograph of a group of costumed performers. “My sister is a fly, my mum is an earwig, and my stepfather is a flea.” It could be one of Hannah’s signature spectacular illusions.

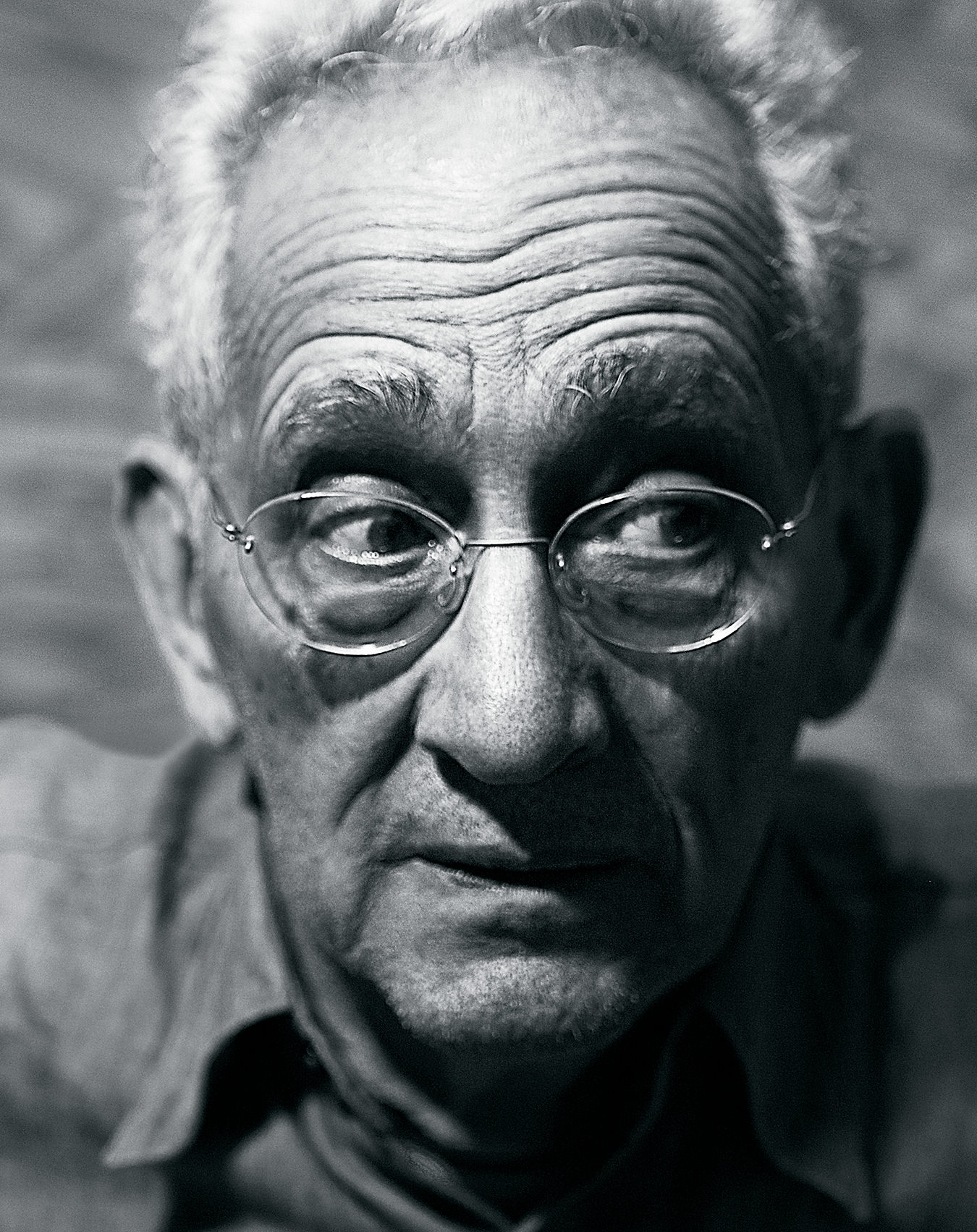

Hannah is a good-humoured 51-year-old who lives in Burnaby, B.C., with his wife, two kids, and a curly-haired dog that perches on his lap for much of the interview. He is also one of Canada’s most respected artists, who has exhibited at institutions in far-flung destinations such as Seoul, Sydney, and Santiago, has received countless honours and accolades, and has works included in many prestigious collections, including the National Gallery of Canada (where he is a board member), Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Ke Center for the Contemporary Arts in Shanghai, and Zachęta National Gallery of Art in Warsaw.

He is renowned for his videos, photographs, and installations inspired by the art and stagecraft genre tableau vivant. In these “living pictures,” actors pose in static scenes that recreate historical events or paintings. For the past two decades, Hannah has achieved national and international success by presenting elaborately constructed, immaculately detailed, almost-but-not-quite-still lives inspired by masterpieces such as Théodore Géricault’s The Raft of the Medusa (1818–19), Auguste Rodin’s The Burghers of Calais (1889), and Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937), as well as the everyday lives of ordinary people.

Photos: Repetition and mirrors are frequent motifs in Adad Hannah’s work—a nod to how, in predigital-camera times, the mirror both momentarily obstructed the photographer’s view when taking a picture and enabled the photograph to be taken.

The photograph of the artist as an insect is not one of Hannah’s tableau vivants, however. It’s a snapshot from his personal archive, taken when he and his family were part of an experimental performance group called Abracadabra. The group toured Europe in the 1970s, at one point briefly teaming up with a theatre company whose props and costumes had been designed by abstract painter Joan Miró. When not on stage, the young Hannah would peruse paintings with his family at world-class museums or roam around with other kids at parties while the grown-ups smoked marijuana. “The kind of hippie mentality was, take your kids with you everywhere, right? So we were always in the action, wouldn’t get sent off with a babysitter,” he says.

Hannah was born in New York and spent his early childhood in Tel Aviv and London before the family settled in Vancouver in 1981, when he was 10. He started going to school regularly at that point, he says. Until then, his attendance had been spotty, but his parents had always supplied books, and he read a lot. Sometimes they would busk on the street, and he would count the money in the hat. “I guess that’s how I would do my math,” he says. When it was Italian lire, the numbers could get really high.

He broke away from the performance group at around 15. Pulling up another childhood photo, he laughs. “You can see on my face I don’t want to be wearing makeup with my parents anymore.” Growing up in such a creative environment, it was perhaps not surprising that Hannah went to art school: first Emily Carr Institute of Art + Design in Vancouver for his bachelor degree and then Concordia University in Montreal for his master’s and PhD. “I spent a long time trying to be straighter than my upbringing,” he says, acknowledging that this was an unusual impetus for becoming an artist. “I never would have shown anybody these pictures even up to 10 years ago,” he divulges, regarding the photo album of his “family of clowns,” as he affectionately calls them.

The tableau vivant pictures are performative, and the setup and production are theatrical. “You’re staging things. You’re lighting things. You’re doing makeup and costumes.” In one of his most recent projects, What Fools These Mortals Be, a collaboration with the Circle Project, he worked with a group of 14 formerly incarcerated women to recreate scenes from Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, presented as an immersive three-screen video.

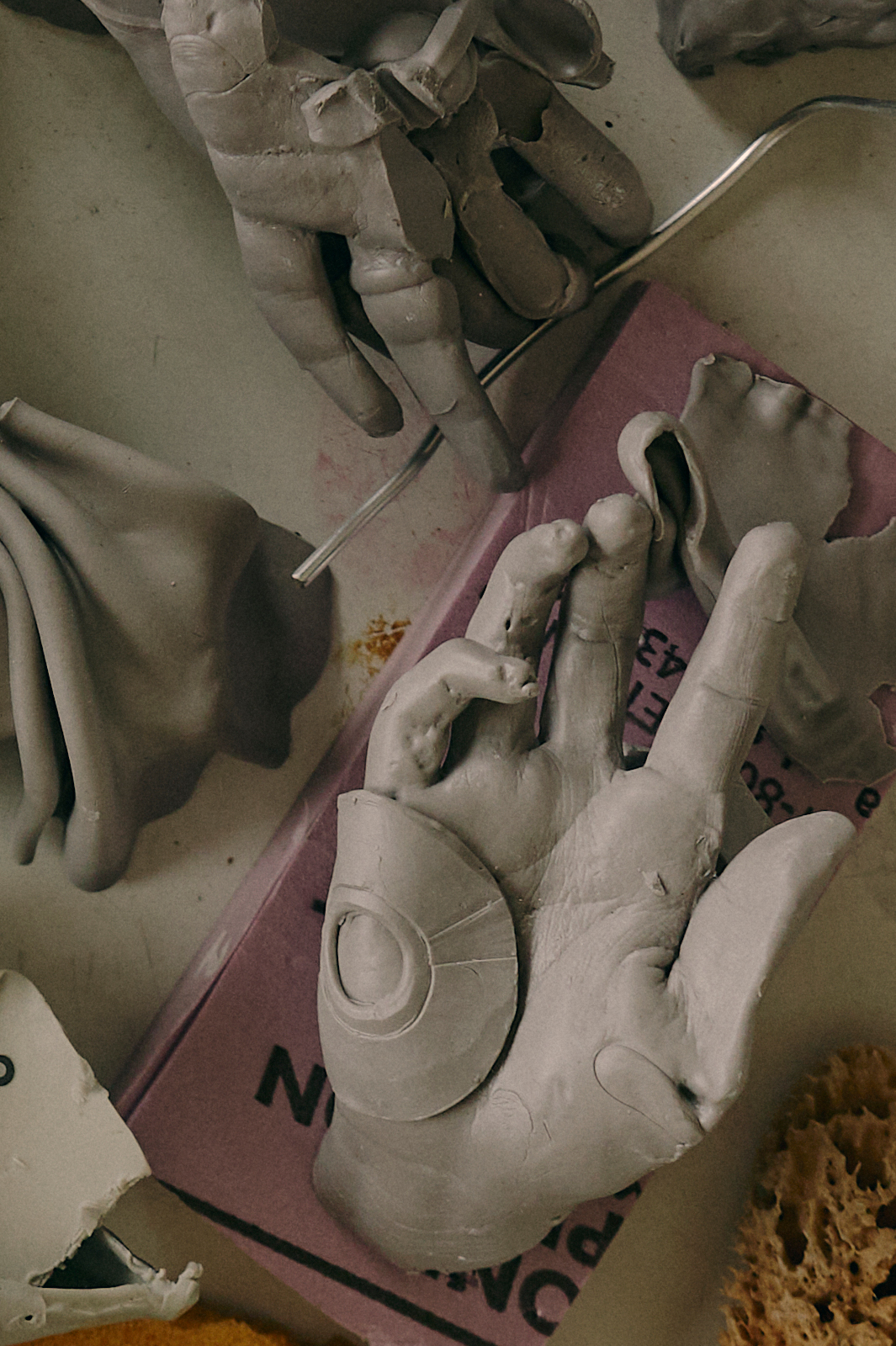

It’s not the first time he’s worked with a community group. In 2009 he travelled to a remote B.C. municipality to make The Raft of the Medusa (100 Mile House) and was then commissioned to do another iteration, The Raft of the Medusa (Saint-Louis), in Senegal in 2016. He often reinterprets Rodin, his PhD subject, and Picasso’s Guernica is another favourite. At the Remai Modern in Saskatoon in 2021, he worked with a group of student volunteers to turn items from local thrift stores into a three-dimensional collage version of the iconic painting, a reference he had previously visited when creating Backyard Guernica (Georgia) in 2017. He’s interpreting Guernica again later this year with a 12-foot-tall, about-20-foot-wide, six-foot-deep bronze sculpture commissioned by a private collector in Vancouver. Maquettes were presented at Art Toronto this past October by his Canadian galleries, Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in Montreal and Equinox Gallery in Vancouver.

Repetition and mirrors are frequent motifs in Hannah’s work—a nod to how, in predigital-camera times, the mirror both momentarily obstructed the photographer’s view when taking a picture and enabled the photograph to be taken.

While Hannah now stands behind the camera in his role of director, not performer, he remains engaged in every aspect of each project and isn’t precious about getting his hands dirty. Those who appear in front of the camera are often intimately involved, too, from the conception of the idea to its execution. Improvisation comes into play as well. “If you think too much about every single step, you can ossify or seize up,” he says. “So I prefer to try to trick myself into taking that step without thinking too much and then go back and analyze it later.” He discusses poses with performers in advance, but once they’re in their positions, which are held for five to seven minutes, Hannah mostly just issues words of support for their acts of endurance: Move slowly. Keep breathing. He might try five different takes, because he doesn’t go in with a fixed idea, he says. “There is no right way, so it’s just testing things, moving things, removing stuff, adding stuff. But that’s all done in the moment.”

___

“Museums always have didactic panels that tell you what something means, but cultural texts don’t have fixed meanings—they’re all contextual.” —Adad Hannah

When he made The Russians, 2011, a video series based on the 1958 photo book The Americans by Robert Frank and inspired by Sergei Prokudin-Gorskii, an early colour photographer, Hannah wasn’t able to communicate with the performers much due to the language barrier. “So there was more movement,” he says. “Since then, I’ve realized the movement is what’s interesting in the end, right? Not the stillness.”

The light-bulb moment when Hannah first hit upon the idea of the tableau vivant turns out to have been candlelight instead. When he was in art school, a book on trick photography inspired him to make an experimental video of himself, his mother, and his wife sitting still while a flame flickered. He showed it during a crit, and his professor enthusiastically introduced him to the tableau vivant tradition.

Initially he was just trying to see what happens when a reductive process is applied to video: “taking away the movement, taking away the action, taking away the audio.” You’re left with something like a photograph, but not frozen in time, with a defined before and after. “That moment expands but also opens that space to wander around the image, to take your time,” he says. The viewing experience becomes active rather than passive.

“Museums always have didactic panels that tell you what something means, but cultural texts don’t have fixed meanings—they’re all contextual,” Hannah says. “We are all historical agents, moving through time and making meaning from what we find around us.” Sometimes, this has resulted in Hannah making work that is eerily prescient, even if much of his source material originates in canonical art history.

Presented in early 2019, a year before the COVID pandemic struck, The Decameron Retold is based on Giovanni Boccaccio’s collection of tales from around the time of the Black Death in the 14th century. Then there was the outtake Hannah found during lockdown from his 2009 version of The Raft of the Medusa in which all players were dressed in PPE—made “kind of as a joke,” he says, in response to the H1N1 virus. When quarantine measures prevented him from his preferred method of working in close proximity with large groups, he improvised, pulling out a long lens and creating 237 Social Distancing Portraits, a series of tableaux vivants featuring ordinary Vancouverites. These are now collected in a book, Between Us: Adad Hannah’s Social Distancing Portraits.

Hannah’s Instagram account is a fun follow, but he brushes off the suggestion that he engages with it as an artistic medium. “It’s a place to dump stuff and relax or chronicle something as you’re doing it,” he says. “On my website, too, I try and show how things come together. This idea of the artist as like a magician, and you don’t see what’s happening behind, all that stuff is kind of nonsense. I don’t think it serves artists, I don’t think it serves people viewing art, or anything, really. So by showing behind-the-scenes stuff, or if I’m mentoring younger artists, it’s all to the goal of showing people how things are done or sharing ideas, because a lot of people think that it’s beyond reach.”

In his more sophisticated productions, the artist does perform a magic trick: he conjures a marvel while simultaneously demystifying the performative sleight he made to create it. In Hannah’s tableaux vivants, we see ordinary people assuming the poses of historical art archetypes that embody beauty, bravery, vanity, tragedy, and more in lavishly decorated sets. We see ordinary people assuming the poses of ordinary people. We see the fragility in their stillness and the fortitude in their trembling. We see people everywhere, across time, geographies, and dimensions, as reflections of our living, breathing selves.