-

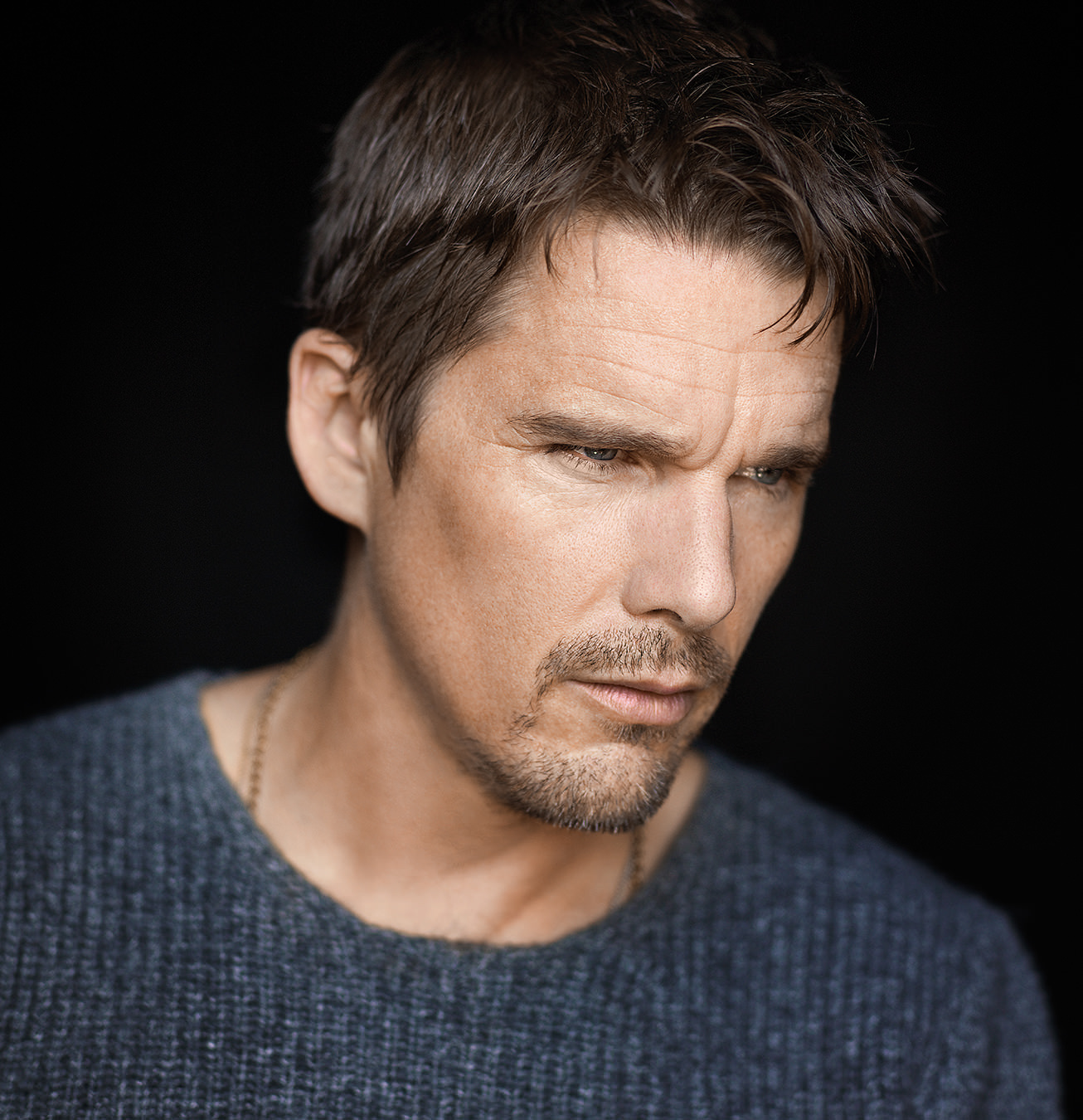

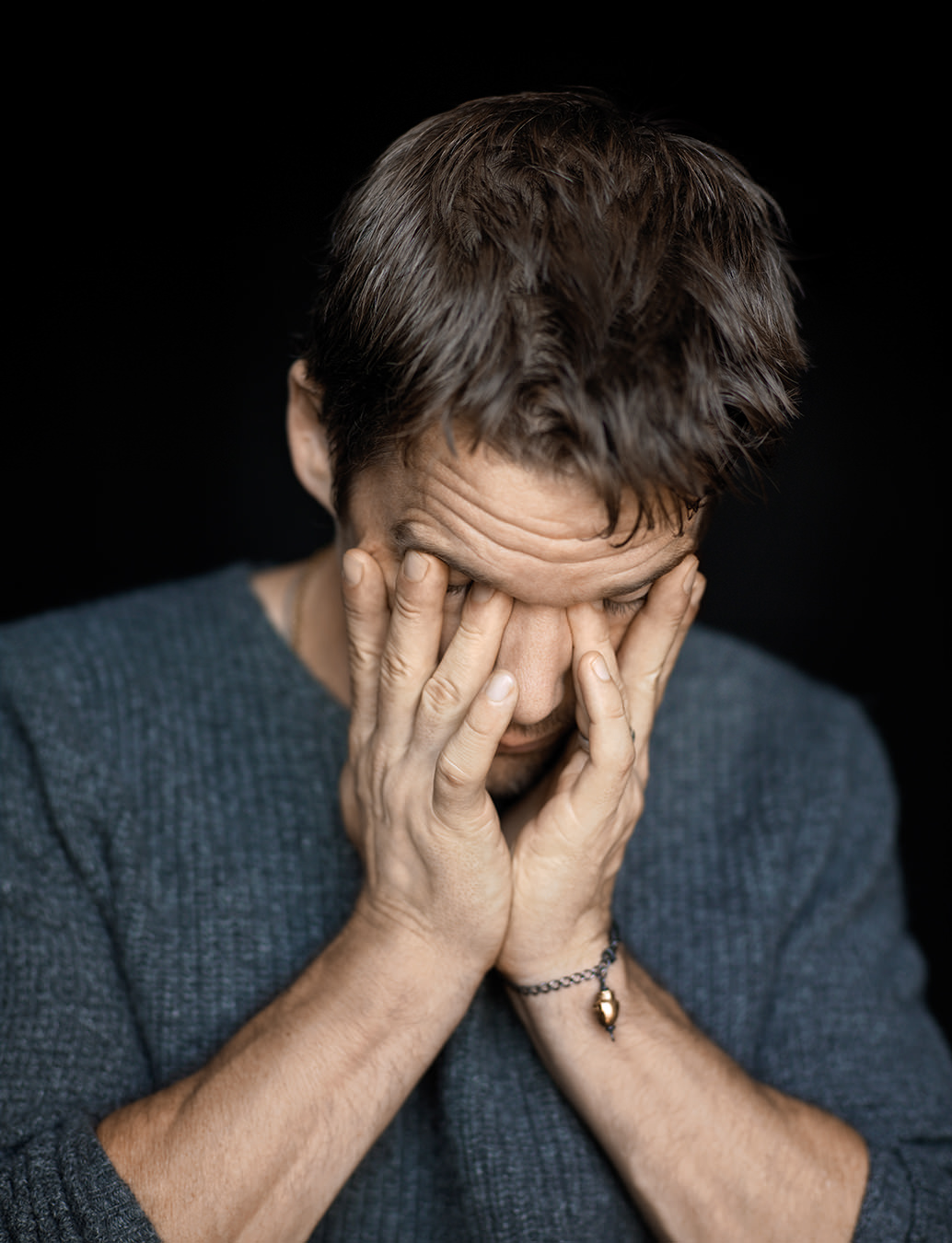

AllSaints sweater.

-

Costume National suit; Alexander Wang cardigan; By Robert James shirt; Still Life NYC hat; Florsheim by Duckie Brown boots.

-

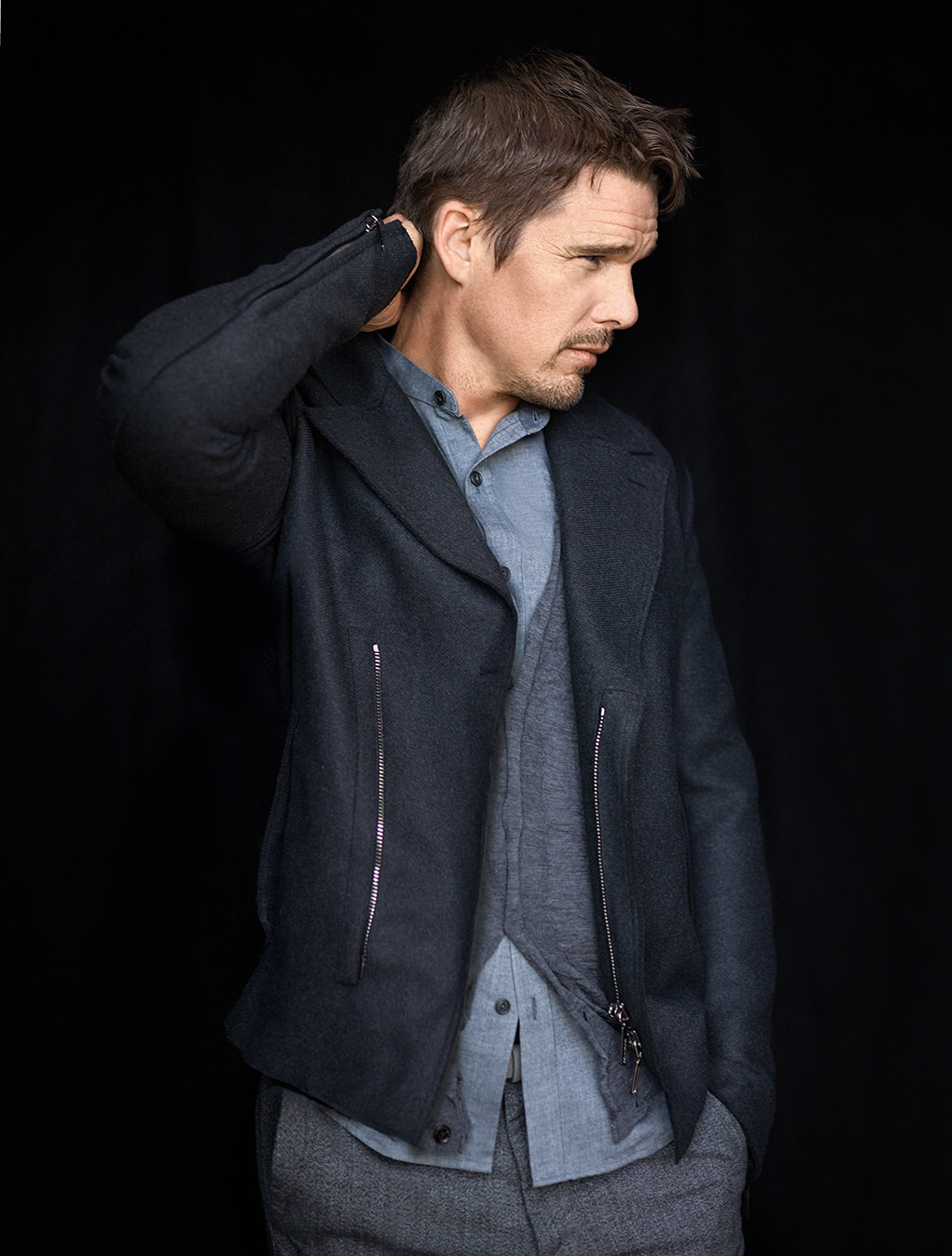

Costume National jacket and cardigan; By Robert James shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; stylist’s own belt.

-

AllSaints sweater and By Robert James bracelet.

-

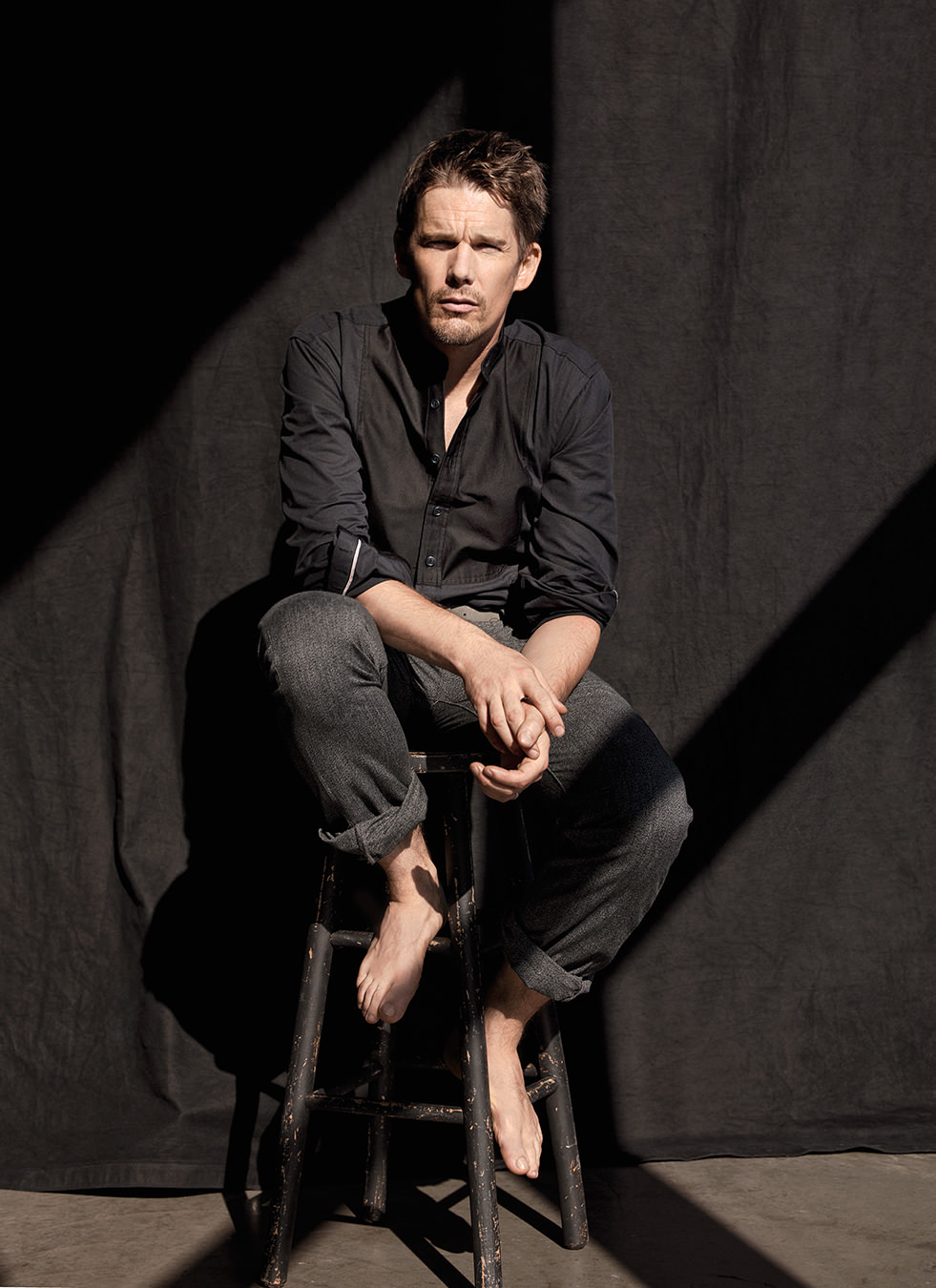

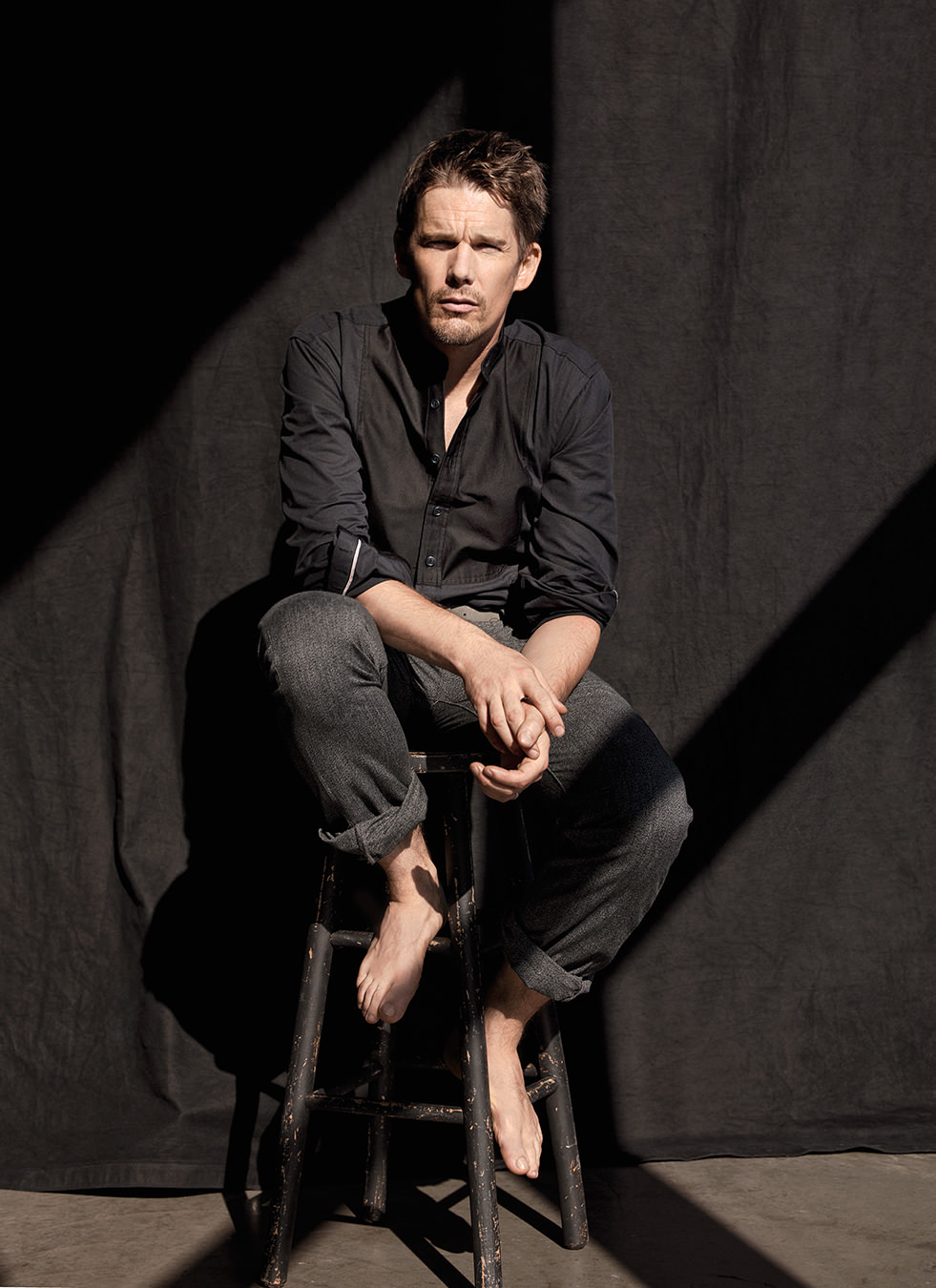

By Robert James shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; stylist’s own belt.

-

On the left: Marc by Marc Jacobs sweater; John Varvatos T-shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; Shipley & Halmos socks; AllSaints boots. On the right: By Robert James vest and shirt; Costume National trousers; Shipley & Halmos socks; Billy Reid boots.

-

AllSaints jacket; Billy Reid sweater; John Varvatos t-shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; Shipley & Halmos socks; and Marc by Marc Jacobs shoes.

Ethan Hawke

A man aloft.

Ethan Hawke walks with the unhurried gait of a man with nowhere to go. His features—blue eyes, permanently terror-wide; a deep, implacable crease running down his forehead; the unchanging goatee—are pale in the light of a sunny afternoon in New York’s Chelsea neighbourhood. His arms are also pale, sticking out from his T-shirt, a navy souvenir from the Stone Pony, the New Jersey bar where Bruce Springsteen got his start. Their formlessness don’t strike one as very cinematic, nor do his corduroys and New Balance sneakers. Hawke, 41, looks worn out and beat—but after 47 movies, 11 plays, and two novels, he has earned the right to be exhausted. Yet his smile, when it flashes, is genuine, and his voice, slightly raspy with just a residual hint of his native Texas, is instantly recognizable. “Let’s get some lunch,” he says, “I’m starving.”

As it happens, Hawke is tired, but not because of his latest film, The Woman in the Fifth, a high-art film set in Paris, co-starring Kristin Scott Thomas, and directed by art-house favourite Pawel Pawlikowski. A few weeks prior, Hawke’s wife, Ryan, gave birth to their second daughter, Indiana. (Hawke has two children, Maya and Levon, with his ex-wife, Uma Thurman and a daughter, Clementine, with his current wife.) “After Indiana Jones?” I ask. “No,” he replies, “After George Sand’s novel Indiana. Stoppard told me, ‘Name her Indiana, the first great female protagonist.’ ” Stoppard, of course, is Tom Stoppard, with whom Hawke worked on the Coast of Utopia trilogy of plays, and George Sand is the 19th-century French novelist, and all of this would be unbearably pretentious if Hawke didn’t end the anecdote with a little chuckle to show that he knew it was, too.

As we walk by brownstones, passersby, and their well-dressed dogs, few seem to notice Hawke. It could be that they’ve grown accustomed to him; he’s lived in the neighbourhood for seven years. Or they might not recognize him, his face not 60 feet high. But it’s not that they don’t recognize Hawke as a movie star; it is as if they don’t register him at all. Hawke seems to slip by unnoticed, tuned to a slightly different station; both grounded and deeply aloof, though less aloft than alone. Apart is his default position.

AllSaints sweater and By Robert James bracelet.

In The Woman in the Fifth, Hawke plays Tom Ricks, an American novelist who spends much of the movie’s 83 minutes being down and out in Paris: a writer scribbling in a notebook in a purgatorial café, a night watchman peering at a grainy television in an underground bunker, an estranged father speaking to his daughter from behind a playground gate. (The film is scheduled for Canadian release in March 2012.) The story is the sort of inexorable slip-knot thriller whose narrative details are immaterial. The turn isn’t in the story but in the idea that stories can be believed at all. One knows not to believe the plot, but, the plot being all there is, one has no other option. “I don’t have any fantasies it will be Toy Story,” says Hawke. “There’s no expectation for commercial success.”

We settle into the back corner booth of an airy restaurant called Cookshop on Tenth Avenue. Hawke defers bottled water for tap. He tells the waitress he prefers “New York’s finest”, perhaps slyly referencing his 2009 cop flick Brooklyn’s Finest, but probably not. Hawke doesn’t do multivalence. “To a fault, I’m sincere,” he says, before noting, ruefully, “This is a time period marked by a sense of irony.”

“Dead Poets Society was the greatest gift that has ever happened to me,” admits Hawke, and after a pause, “[It] sent my life completely off course and I’ve been trying to recover since. It’s Shakespearean.”

Without a doubt, Hawke is a man out of step with his time. While moviegoers crave superhero blockbusters in which the mutants stop just short of winking at the camera, or independent films where internal struggle is expressed by wistful whimsy and elliptical mumbled phrases as if to undermine the dramatic cortisone of cinema, Hawke’s work is shamelessly straightforward even when his films aren’t. He’s James Franco minus the meta-smirk. The Woman in the Fifth, which will infuriate narrative literalists, still posits faith in Cinema, big C, and Art, big A. “I felt as if I was working with a serious artist,” says Hawke of Pawlikowski, “and if the movie doesn’t make sense to anyone else, it makes sense to him, which in the long run is how you make good art.” Hawke pauses. He fixes the waitress with his wide blue eyes and, opening his soul to hers, orders fish tacos.

By Robert James shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; stylist’s own belt.

To see the world in a grain of sand, or Hawke’s trajectory in a single role, one need only visit his breakout film, Dead Poets Society (1989). Here is young Ethan Hawke as Todd Anderson. Hawke was 18 but playing younger; lamblike eyes, an unfurrowed brow, the goofy smile spreading slowly, he is the model of innocence. He is sincere, too naive not to be, and heartbreakingly vulnerable, his shell not yet hardened. There he is, in a cave, reading Walt Whitman, cocooned against the callous world, and there he is, crestfallen and betrayed, the world intruded, shell-shocked, shell-cracked when his mentor—Robin Williams at his dramatic prime—is exiled. And there he is at the end of the film, standing on his desk, making a stand on his desk, shouting, “O Captain! My Captain!” The image is indelible. “Dead Poets Society was the greatest gift that has ever happened to me,” admits Hawke, and after a pause, “[It] sent my life completely off course and I’ve been trying to recover since. It’s Shakespearean.”

He also admits, “The fundamental experience of my childhood was very lonely. Fame immediately places a glass wall between you and your peers.” Growing up, Hawke felt the isolation acutely. “It makes people—people who love you, people in your family—go far away. The best of people don’t want you to think they want anything from you, but who doesn’t want something from you? Nobody’s authentic.” Hawke turned to film, where the interactions were at least scripted, to forge his identity. He played Jack Conroy in White Fang, a boy whose only true companion is a wolf-dog, and shortly thereafter, he played a resilient plane-crash survivor in Alive (1993). He starred in the 1990s touchstone Reality Bites as Troy Dyer, a soul sensitive to the point of paralysis. But perhaps his most impressive role—and one he brings up often—was Jesse in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise. In it, Hawke plays a young American in a foreign land who is looking for human connection—which he finds, but only for the night. He toyed with mainstream stardom in Great Expectations, but left uneasy. In a climactic scene, Hawke kisses Gwyneth Paltrow while the rain pours down and the music swells. “When I saw that, I just thought, ‘Man, if this is what people think kissing a girl is like, they’re going to be really disappointed.’ ” Later, he played a modern-day Hamlet, reciting the famous “To be, or not to be” soliloquy in a Blockbuster video rental store. It may be the closest Hawke ever came to winking at the camera.

Now, Hawke is moving into television with Blue Tilt, a police drama co-starring Vincent D’Onofrio (picked up by NBC). Hawke cites his growing family and the ability to work from New York as contributing factors, but it’s clear from his work on films such as Training Day, Assault on Precinct 13, and Brooklyn’s Finest that he’s comfortable in the police uniform. After all, a man patrolling the streets wearing NYPD blue is aloof, though less aloft than alone.

When Ethan Hawke hears something he wants to remember, he whips out a ballpoint pen and scribbles it on his arm. It’s a Holden Caulfield–like habit, self-consciously literary, but endearing nonetheless.

When Ethan Hawke hears something he wants to remember, he whips out a ballpoint pen and scribbles it on his arm. It’s a Holden Caulfield–like habit, self-consciously literary, but endearing nonetheless. By the time we leave lunch to take a walk on the High Line, that stretch of abandoned elevated railway recently redone as a city park, his arm is self-tattooed: Brecht. Typewriter. Louie C.K. A code inscrutable to others, but heartening. After all these years, he remains enthusiastic. Hawke asks more questions than he provides answers, but when he speaks his mind, it’s as if he’s discovering its contours himself. He quotes Bob Dylan, Dostoevsky, and Ken Kesey in the same breath. Of the latter he says, “One of the things acid did for Kesey was to realize the futility of any sort of commercial or perceived success. He understood how history crushes us all.” We head up the stairs to the park.

AllSaints jacket; Billy Reid sweater; John Varvatos t-shirt; Rag & Bone trousers; Shipley & Halmos socks; and Marc by Marc Jacobs shoes.

Hurricane Irene has just passed over the city, but the day is sunny and the wild flowers—big bluestem, leadplant, wild spurge—rustle in the residual wind. “I remember when this place was deserted,” Hawke says. “It was a great place to come with a girl and a bottle of wine.” For a moment, one can imagine Hawke as a normal boy but the scene comes through the haze as a full-blown scene from a movie, about as real as a field of grain on the West Side Highway. For Hawke too, his self is mediated by the screen. “From a young age,” he says, “I saw myself in the third person … I have no concrete, developed inner life.” So we pause to imagine him as a teenager, on this spit of elevated land, carefully laying a blanket on the ground overgrown with weeds and littered with broken glass, the sun somewhere over Hoboken, a bottle of cheap port in a backpack and a sweetheart on his arm. One knows not to believe the plot, but the plot being all there is, one has no other option.

From the way Hawke talks about the Theatre, big T, and the Arts, big A, it’s clear he deeply believes in their sanctity. “Brando, on closing night of Streetcar—now that was immortal,” he says, with no self-aware chuckle. “Fleeting but immortal.” Later, he says, apropos of little, “I was reading Allen Ginsberg’s ‘America’—it is such a phenomenal poem!” He shakes his head in wonder. Hawke’s sincerity can irk. It seems somehow arrogant, or at least presumptuous. The youthful innocence in Dead Poets Society, so touching in a boy, has soured in a 41-year-old to smugness. Hawke is generally seen as insufferable, sincere to a fault. But might these feelings have more to do with our reaction when confronted with vulnerability and its brash request for empathy? Come from behind your bulwark, it asks, a babe in no man’s land. Might we not feel somehow ashamed by his continued exposure and so attribute arrogance to his openness? This instinctual unease has dogged Hawke since the days the fathers and teachers of Dead Poets Society’s Welton Academy foamed with rage when confronted by the spectre, so pure at heart, of “a bunch of guys reading poetry.” Walking a storey above the street, another mournful Ginsberg line, from his elegy “Howl”, springs to mind, of “angelheaded hipsters … who faded out in vast sordid movies, were shifted in dreams, woke on a sudden Manhattan.”

But I’m too self-conscious to quote it, and, besides, we’ve reached the southern terminus of the park. A glass wall signals the end of the line and beyond that, a drop. Hawke leans over, glances left at the city and right to the river. Then he says, “Let’s turn around.”